When Sick Cattle Were Alleged Victims of Arrow-Wielding Elves

For centuries, farmers suspected their sick livestock had been “elf-shot.”

In Scotland, a sick cow was a sign that something supernatural was afoot. Whether weak, milk-less, or just a little bloated, an unhealthy heifer in the Anglo-Saxon world was a big problem—and a fantastical one at that. According to many interpretations of medieval and modern-era Anglo-Saxon folklore, sick livestock were likely victims of hard-to-see, sharp-shooting elves. Their condition, referenced for nearly a millennium in charm books, folklore, and documentation of witchcraft, was known as, simply, “elf-shot.”

Throughout the early and medieval Anglo-Saxon world, elves occupied a shifting but ever-important role in the natural, supernatural, and mortal worlds. Early Anglo-Saxon conceptions of elves envisioned the other-worldly beings to be more similar to humans or gods than monsters or dwarves. Though distinct from demons and beasts, elves still had a slightly sinister side. A witch’s orders, indignation at an unknowing step into elf territory, or a mere whim might prompt an elf to shoot dagger-like arrows at the unsuspecting cow.

The first mention of “elf-shot” appears in Anglo-Saxon Leechbooks, or healing books, as early as the mid-10th century, according to Jennifer Culver, professor of English at Texas University. Arrow-pierced cows showed symptoms ranging from loss of appetite to labored breathing. Often, they were reported to have grown thin and lost their ability to produce milk. In Ireland, one man wrote, “the animal’s hair stands up on her back, her ears lifeless and hanging.”

Perhaps because the symptoms were so varied, cures, too, ran the gamut. Most surefire antidotes included a charm or incantation, to be uttered alongside a slightly more physical ritual. According to one 20th-century text, a farmer in Selkirkshire might “take a blue bonnet that had been worn by the oldest member of the family, and with it ‘rub the cow all over, and the wound will make its appearance or the place will be seen where the wound has been.’” No bonnet? Another regional cure enlisted a local wise woman to jab the afflicted cow with a needle, fan it with a leaf from the bible, and mutter incantations. In Shetland, one might fold “a sewing-needle in leaf taken from a particular part of a psalm book” and secure it “in the hair of the cow.” In northern England, “elf-shotten” calves were given a particularly unsavory treatment in which farmers would rub their “mouths, lips, and nose with their own dung.”

According to Dr. Culver, one common cure came from the ocean. Historian and author Audrey Meaney has theorized that jagged fossils of belemnites, a squid-like mollusk that became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, were thought to be tiny daggers. The pointy specimen looks like a small, broken arrow, and, when discovered on the shore, was assumed to have a sort of sympathetic power to keep other supernatural darts at bay. “They could be draped on the livestock, or hung over barns or stables to protect the animals,” says Dr. Culver. “Or farmers would dip them into the water, and the cow would drink the water that they were dipped into.”

It wasn’t just cows who were believed to be afflicted. Humans, too, could be struck by an elf—particularly if they had wandered into territory controlled by elves. Though symptoms and treatments varied a little between species, what seemed to universally puzzle people about the affliction was the combination of sudden illness and lack of visible wound. “Imagine you’re walking next to someone who seems fine, but all of a sudden that person grabs his chest and starts to lean over, feeling as though he’s being stabbed,” says Dr. Culver. “There’s no way to describe how it happened, or where it came from, and there aren’t any outside marks.”

Because internal diseases, such as distemper for cows, or heart attacks for humans, weren’t visible, folks clung to what they could see. And there’s evidence that small, ancient arrowheads might have played a part in fleshing out the elf explanation. 20th-century scholars such as Thomas Davidson argue that neolithic flint might have been mistaken for small arrows. The consistency in shape and size of the archaeological finds, writes Davidson, made a compelling case for tiny beings creating tools. In the early 1700s, one Reverend wrote a letter proclaiming how strange it was “that these elf-stones … fall from the aire. The commonality superstitiously imagines that the fairies hath made and gives them that shape, and that they doe hurt by them, which we call elf-shot.”

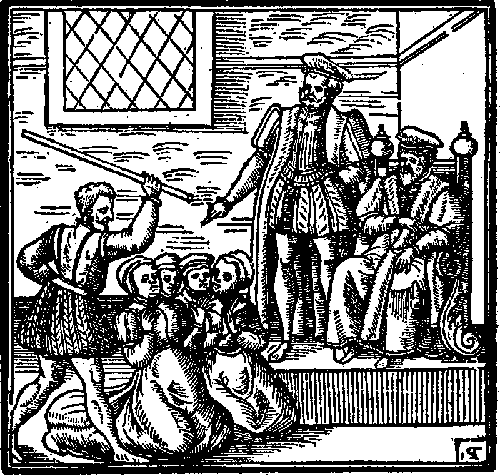

According to Dr. Culver, elves made it into Scotland’s infamous witch trials, too. The shifting conception of what elves were, and what they were capable of, eventually morphed “from deities to less powerful ones that humans can command to do their bidding.” Women accused of being witches, such as Isobel Gowdie, were convicted for instructing devilish elves to sling magical darts at livestock with some kind of charm.

Not all scholars, however, agree that people seriously believed arrow-wielding elves brought on the bug. According to author and lecturer at the University of Leeds, Alaric Hall, no darts, arrows, or piercing instruments were involved in the process at all. Instead, he says, we’ve been misinterpreting “elf-shot” to mean, literally shot by an elf, when it was actually a more idiomatic way of talking about a sudden strike of pain. A series of mistranslations and misinterpretations of Old English words associated with medicine and pain have led to an overly elf-centric understanding of how people once viewed disease.

That people could have believed in tiny, dagger-slinging creatures capable of taking down herds of cattle might be hard to swallow, but the need to assign meaning to something seemingly inexplicable is universal. Whether we’re musing on extraterrestrial life or self-diagnosing a strange bump, bruise, or unfamiliar illness, many of us still feel compelled to explain the unknown that exists in the natural world and inside our own bodies. Like those who claimed neolithic arrowheads must be elf-made tools, we, too, search for hard evidence to explain nebulous narratives. All elves aside, the unknown remains dark, deep, and, sometimes, a little whimsical.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook