In San Francisco, an East German Restaurant Is a Portal to the Past

Familiar foods such as “cold dog” offer former Eastern Bloc residents a taste of their youth.

It’s a buzzing evening in San Francisco’s Mission District, but walking through the front door of what is perhaps the only East German restaurant in the United States feels like stepping into another country, as well as the past. At Walzwerk, framed illustrations of Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels share space along one of the eatery’s walls, and a large poster extolling the quality of the former East Germany’s Maxhütte steelworks hangs on another.

The cozy two-room space is heavy with the scent of sausage and sauerkraut, and the only server floats between customers, delivering plates of herring and steaming bowls of potato soup. On the restaurant’s outside entry is a metal sign reading “You Are Now Leaving the American Sector.” That’s pretty accurate. By serving East German cuisine, Walzwerk is a portal to life behind the Iron Curtain and to a state that no longer exists.

German native Christiane Schmidt opened Walzwerk with her then-business partner Isabell Mysyk in the fall of 1999, 10 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall—a key event in Germany’s reunification and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Schmidt, who grew up in the former East German state of Thuringia, was actually living in Berlin on November 9, 1989, when guards opened the borders between East and West Germany. “The next day Americans flooded the city,” Schmidt says, “and it was an amazing place to be at that moment. Suddenly, the world was accessible.”

After meeting Mysyk in Germany, the two decided to move to the United States and start a business. “Everything here that was German had a Bavarian ‘beer hall with lederhosen and blue-checkered tablecloths’ theme,” says Schmidt. “Isabell and I wanted to do something different. It seemed like people were really interested in the history of what life had been like in East Germany, so we decided to focus on what we knew.”

The two women used $40,000 of borrowed funds to start Walzwerk, and after a review in a local newspaper, Schmidt says, the place packed in crowds for 10 straight years. For Westerners, Walzwerk was a place where they could learn the history of the German Democratic Republic and sample a forgotten cuisine. For former Eastern Bloc residents, on the other hand, the restaurant is a trip down memory lane. “People who lived in East Germany are shocked when they come in here,” says Schmidt. “I’ve had several customers say it’s like walking into their friend’s living room [back in the GDR]. That’s a real compliment.”

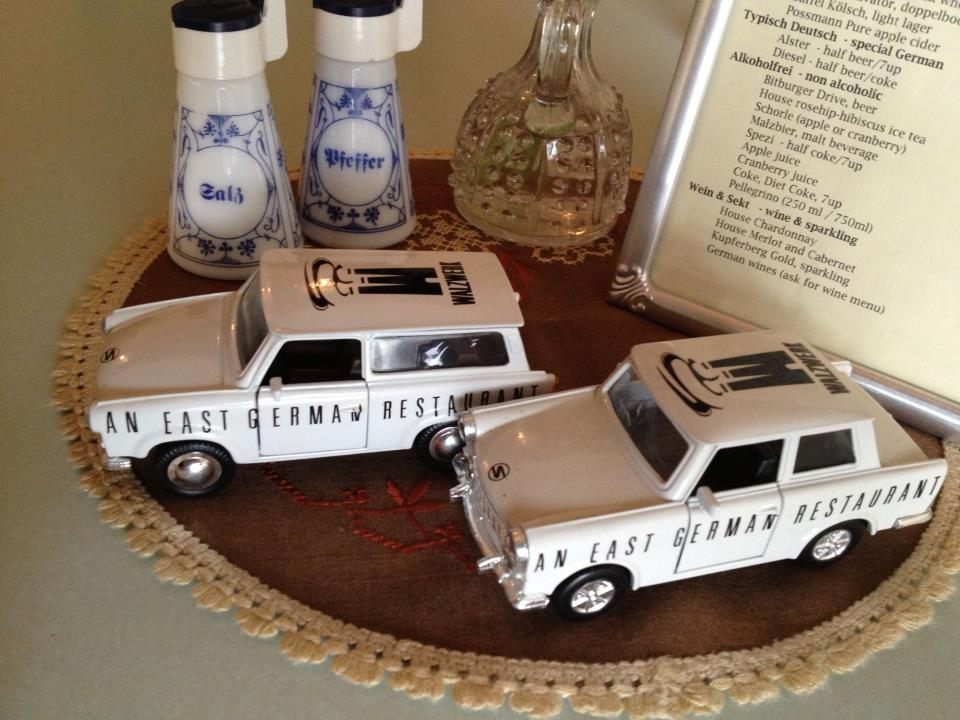

In fact, GDR memorabilia is everywhere. At Walzwerk’s tiny two-stool bar, a glass countertop displays a series of small Trabants—plastic models of East Germany’s most infamous car. In the restaurant’s back room, a figure of the beloved children’s television character Sandmännchen, or Little Sandman, watches over diners from a corner shelf. One of the restaurant’s most divisive pieces of East German history is its framed portrait of Erich Honecker, the former GDR leader who oversaw construction of the Berlin Wall, which hangs prominently above the restaurant’s front door. “There are some customers who will purposely turn their backs on him while they eat,” Schmidt says.

But it’s not just the atmosphere that attracts business. Walzwerk’s menu is an ode to the dishes that Schmidt’s and Mysyk’s mothers and grandmothers used to make. These include hearty East German meals such as Thuringian bratwurst with mashed potatoes and sauerkraut, soljanka, a meat-heavy Russian soup that became popular in countries throughout the Eastern Bloc, and cabbage salad—an inside joke for East Germans, says Schmidt, who’d walk into a produce market and see nothing but white cabbage to the left and to the right. “It was everywhere,” she says, laughing. For dessert there’s kalter hund, or “cold dog,” a chocolate and butter-cookie layer cake that Schmidt would enjoy every year on her birthday.

Still, some of the items are more generally German. “We never had schnitzel in East Germany,” she says, “but we have it here. Customers expect it.” Trout is another non-GDR delicacy, and chicken breast is possibly the menu’s least East German dish. “People today eat differently than they did 30 years ago,” Schmidt says. “We try and honor this, and the fact that we’re a German restaurant in California, while still being traditional and adhering to our roots.” For the most part, however, Walzwerk’s food offerings have stayed pretty much the same for 20 years. “People come here because they want to feel at home,” she says, “and this means knowing their favorite dishes will be here when they come back.”

It’s this kind of comfort that keeps Walzwerk’s clientele coming back. They include families with young children, local residents-turned-regulars, and the restaurant’s many Germanophiles, who Schmidt describes as “people who want to go to Germany, who are learning or want to learn German, or who just really love schnitzel and beer.” They come to see Schmidt as well, since the owner works the floor several nights a week, sometimes hosting, busing, and serving food and drinks on her own.

Customers also drop off gifts: colorfully printed tablecloths they’ve picked up at German flea markets and mismatched plates and tea cups, especially the kind once typically found in East German cupboards. “That vase over there,” says Schmidt, pointing to a small ceramic vessel atop one of the tables, “my mother used to have those.”

Today, Walzwerk remains a time capsule of East German history, cuisine, and a culture that otherwise only exists in memory. “If you grew up in a country that’s suddenly gone,” Schmidt says, “there are things you are going to miss. [At Walzwerk], we wanted to show people a different Germany. It wasn’t a political statement. In the end, it’s just where we’re from.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook