The Carnivore Paradise That Keeps Changing the Story of Human Evolution

New research at Dmanisi continues to challenge what we think we know about our deep past.

To visit Dmanisi, one of the most important sites in the story of human evolution, head south and then west from the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, along a narrow highway crowded with delivery trucks. After an hour, turn onto a road that runs through ever-smaller villages. There, sheep clog the way, ignoring the shepherds, who cross the pavement back and forth on horseback. The road narrows again and sinks into a ravine, following the twisting course of the Mashavera River through thick forest and shadow. Feral dogs lounge along the roadside, sizing you up. Park your car in a small lot and walk up a wooded slope, and then the view opens: You’re standing on a wedge-shaped promontory, the Mashavera running far below, with forest, field, and black basalt hills stretching for miles in all directions.

The site is barely 10 acres, dominated by medieval ruins and a small working monastery where monks tend hives of dark Caucasian honeybees. Take away the buildings, however, and the surroundings haven’t changed much from 1.77 million years ago, when Dmanisi was a biodiversity hotspot and home to a unique assemblage of carnivores, including several big cat species, from Africa, Europe, and Asia. Fossils found there also include remains of the earliest known hominins outside of Africa. Since the late 1980s, when this paleontological treasure trove was first discovered by archaeologists digging for medieval artifacts, it has become a lynchpin for understanding how species, including early humans, dispersed across continents.

“I’ve excavated in a lot of places: Texas, Israel, Crimea, all kinds of sites,” says University of North Texas geoarchaeologist Reid Ferring, who has worked there for nearly three decades. “Some of those sites change people’s perspective on the past. Dmanisi is one of those sites.”

More than a mere snapshot of the past, the site is helping researchers advance science itself. For example, in 2019, researchers used ancient proteins extracted from a rhinoceros tooth found at Dmanisi to show that the molecules could be used to build rough family trees and determine how species were related, “beyond the currently known limits of ancient DNA preservation,” the authors wrote.

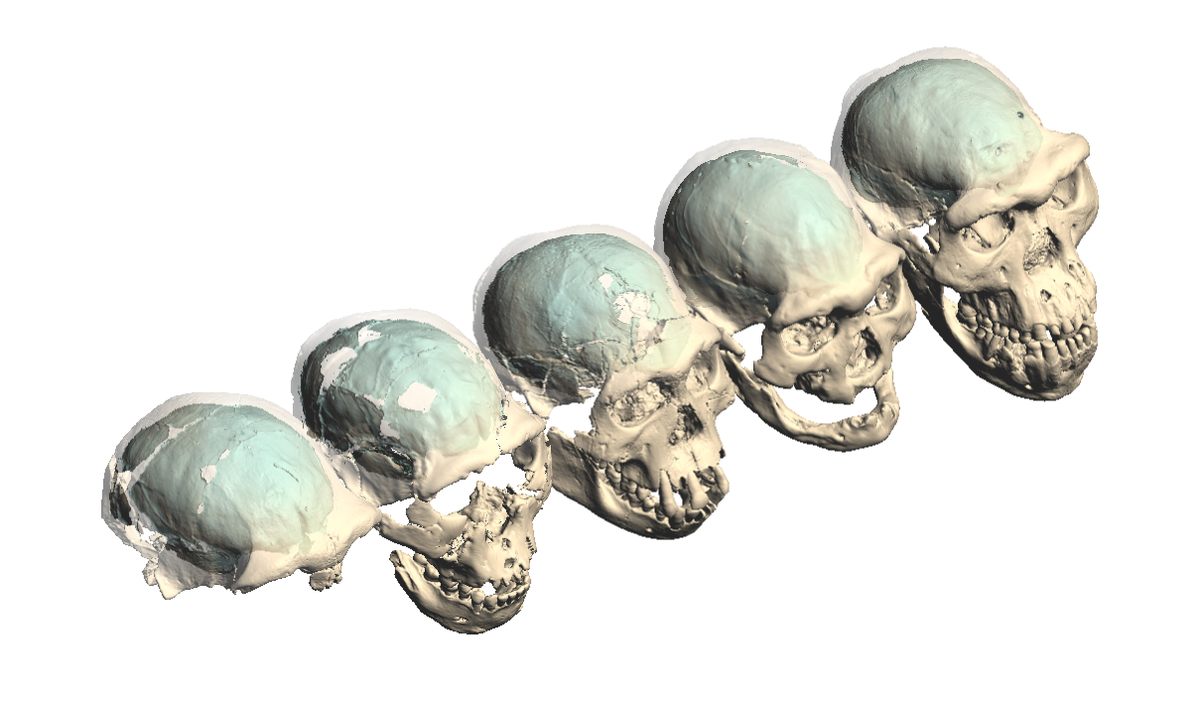

Now, a team led by University of Zurich evolutionary anthropologist Marcia Ponce de Leon published an analysis of the likely brain organization of the Dmanisi hominins, upending a long-held belief that many quintessentially human behaviors require big, complex brains. “The Dmanisi hominins had surprisingly primitive, ape-like brains,” says Ponce de Leon. “However, (they) ventured out of Africa, produced a variety of tools, exploited animal resources, and cared for elderly people. These people with their small, ape-like brains were able to master cognitively demanding tasks. This is really astounding. They provide a completely new perspective on what these behaviors mean in terms of brain evolution.”

In addition to making tools and caregiving—one of the five partial skulls found at the site belonged to an elderly, toothless individual who would have been unable to eat on their own—the Dmanisi hominins, early members of the genus Homo, managed to survive in the middle of what appears to be an extraordinary concentration of big carnivores.

Ferring, who was not involved in the new study, says that Dmanisi stands apart in the fossil record for a combination of reasons. The site itself is in a transitional region, or ecotone, between Georgia’s wet, humid west and its arid east. It is also along a migratory path for animals that summer at higher elevations near the Caucasus Mountains to the north. The promontory overlooks the confluence of two rivers with narrow, deep valleys that naturally concentrated the animals. “It was the perfect place for carnivores,” says Ferring, “and I include humans in that group.”

The more than 10,000 animal bones excavated from the site so far include at least 50 mammal species that reflect the region’s position at the crossroads of three continents: rhinoceros, elephants, deer, ostriches, and horses. And oh so many carnivores: the coyote-sized Etruscan wolf, two species of saber-toothed cat, lynx, bears, giant hyenas, the lion-sized European jaguar, and the ecosystem’s fearsome apex predator, Acinonyx pardinensis, a giant cheetah.

“Dmanisi has the strangest fauna,” says Ferring. It suggests, he says, “you’re looking at a patchwork of forest and grassland. There was something there for everybody, which explains the diversity.”

In this carnivore-rich ecosystem, the early humans were more likely scavengers than hunters—and also sometimes dinner. Some of the animal bones show signs that the hominins butchered them, slicing off meat with stone tools, and some of the hominin bones have gnaw marks. Ferring believes that resource-rich Dmanisi may have been a good spot for a carnivore to raise a family. There is evidence that many of the bones were deposited in burrows dug by animals or in natural, nest-like folds in the promontory’s basalt. “The carnivores found the perfect place for denning, which means they were bringing food to their young,” he says.

Other researchers, including Ponce de Leon, believe Dmanisi’s water-rich landscape simply attracted animals of all varieties, and that heavy rainfalls may have washed their carcasses into the folds and pockets of the basalt.

However the animals came to be concentrated at Dmanisi, the carnivore’s paradise was short-lived. Researchers have been able to date the site with confidence to 1.77 million years ago because nearly all the fossils come from a single layer in the rock, known as B1. It’s sandwiched between two layers of volcanic ash, which can be precisely dated. Ferring believes that Dmanisi may have been a biodiversity hotspot for less than 10,000 years, and possibly only for a few centuries. Then it was buried, quickly but gently, by ashfall from regional volcanoes that preserved its strange history “as a time capsule, until today,” says Ponce de Leon.

“The factors that led to Dmanisi still astonish me, and I don’t use that word in a casual way,” says Ferring. “The preservation of the record is nothing less than incredible.”

That preserved record also offers us unprecedented insight into our own past. Ponce de Leon runs down a list of ways the site has changed—and continues to challenge—what we know about the human story, including that small-brained hominins were even capable of dispersing across continents. “Dmanisi is always good for a surprise,” she says. “Human biological variation, human development, human cognition … almost every possible aspect of paleoanthropology can be investigated there.”

Leaving the parking lot below Dmanisi, coasting down the slope back to the river road, you may sense an echo of the ancient past when you meet the gaze of the shaggy feral dogs—once again two carnivores locking eyes, sizing each other up.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook