Found: Hot Pink ‘Pagodas’ at the Bottom of the Sea

A deep-sea expedition uncovers a candy-colored oasis off the Gulf of California.

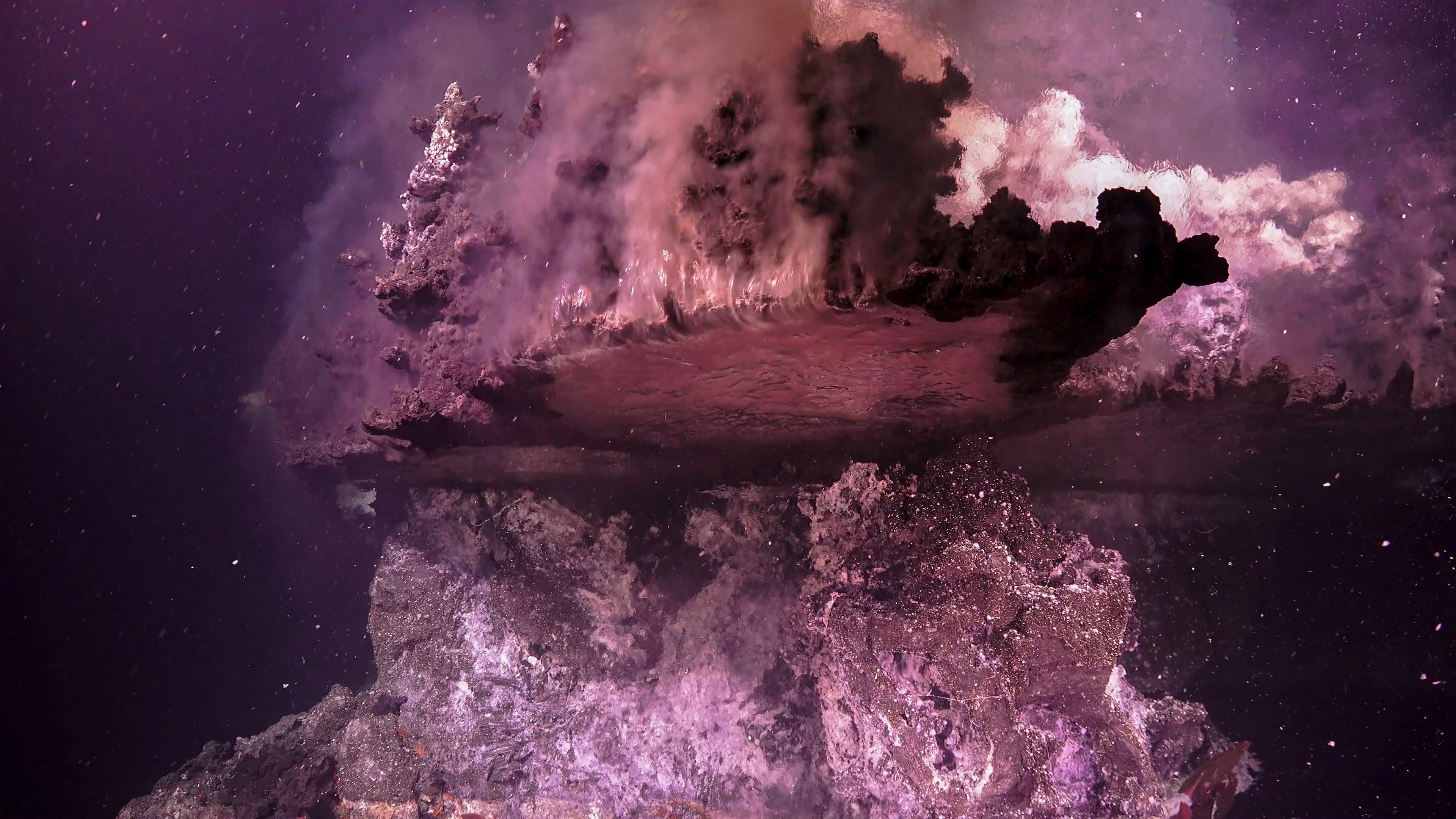

Around 6,500 feet below the Gulf of California, Mexico, the seafloor hosts a candy-colored light show. Hot pink, orange, and snow-white plumes strobe out from a deep sea valley ridged with pagoda-shaped hydrothermal vents, called volcanic flanges. There are “mirrors pools,” too, upside-down puddles of vent fluid that reflect back whatever swims beneath them in a deep-sea mirage.

While conducting a routine survey of microbial communities that dwell around hydrothermal vents, Mandy Joye, a microbiologist at the University of Georgia, discovered one of the most colorful chemical hotspots in the ocean. Joye’s team previously surveyed the area in November 2018 with a mapping bathymetry robot, which stumbled upon a patch of craggy topography that resembled mountains at the bottom of the sea. Joye returned to investigate the site in late February 2019 in an expedition on the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel, funded by the National Science Foundation. What she found was astonishing: an entire valley of massive hydrothermal vents spewing sherbet-colored fluids.

Joye’s team initially expected to discover some novel microbial habitats, but no one expected anything on this scale. The largest of the towers reached up to 75 feet high and 32 feet across. And each vent rippled in volcanic flanges, horizontal ledges that build up as hydrothermal fluid flows out of the vent and reacts with the surrounding seawater. When 350-degree-centigrade hydrothermal vent fluid meets two-degree boring old seawater, spontaneous sulfides precipitate to create insoluble structures that harden like rock.

Joye likens the structure of these vents to a blood vessel: There’s one central artery and many smaller capillaries that each feed out into a flange of their own. The team observed flanges of an enormous size, some reaching 13 feet across and seven feet deep. Researchers often call these vents “pagodas,” as the flanges can resemble the jutting eaves in traditional Asian architecture. One flange looked so distinctively like a spaceship that Joye’s team nicknamed it “the Millennium Falcon.”

What surprised Joye the most, however, was that the plumes erupting from the flanges were shockingly, unabashedly pink. “We never saw pink before,” Joye says. “It looked just like someone blew cotton candy over these rocks to create pink pagodas! So wispy, beautiful, and cloud-like.” While the deep sea abounds with charismatic bioluminescent animals—popular examples include the anglerfish and comb jelly—biochemical reactions are just as colorful. “Biochemistry requires metals, and metals have color,” Joye says. “It’s just a big flashing beacon that’s saying, ‘This is a super fascinating biomolecule.’”

The underside of each flange holds a seemingly mirrored pool that gave rise to these pink and orange plumes. This mirage happens due to the exceptionally high heat of the hydrothermal fluid, which Joye describes as a “funky and bizarre” soup of toxins. “These pools stink of hydrogen sulfide, and they’re charged with metals like arsenic and selenium and mercury,” she says. So for an organism to thrive around these vents, their biology must be capable of taming an unimaginably toxic chemistry.

Aside from these otherworldly vents, Joye also uncovered something eerily familiar. Heaps and heaps of trash littered the seafloor, including mounds of fishing line and plastic bags, an artificial Christmas tree, and a Mylar balloon emblazoned with the smiling face of Elsa from Disney’s Frozen. “It takes your breath away when you see these majestic incredible natural wonders, and then you pivot 20 degrees to the right and there’s a trash heap,” Joye says.

In the coming months, Joye’s team will study the microbial samples they retrieved from these vents, assessing the organisms’ metabolism and genomics. They want to better understand the relationship between geochemistry and temperature in creating an extreme environment in which only a microbe could thrive.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook