The French City Where a Midday Firework Marks the Start of Lunch

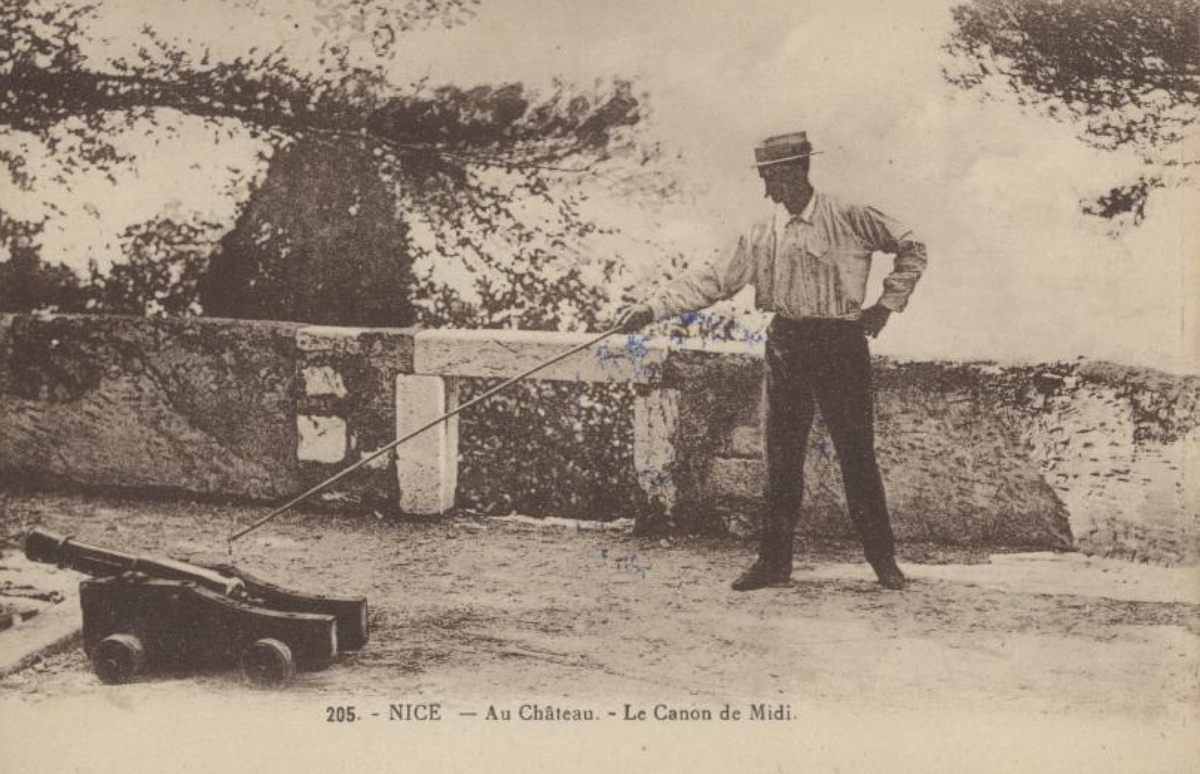

Philippe Arnello is the custodian of the daily cannon—a 150-year-old tradition in the coastal city of Nice.

When the clock struck noon on May 11, the day that France began to lift its COVID-19 lockdown, a celebratory boom echoed through the city of Nice. The midday firework was not a response to the gradual ebb of a pandemic, however—it was a return to a decades-long tradition. “Just like towns have their church bells, the countryside has its roosters, and fields have their cows, for the last 150 years, Nice has had its cannon,” Philippe Arnello wrote on Facebook that morning.

The gloomy weather and requisite face mask couldn’t conceal Arnello’s delight to be returning to his patch of Castle Hill, the original settlement of the southern French city, after eight weeks. “So happy to be able to resume this tradition,” he wrote. Arnello is a second-generation pyrotechnician who has been responsible for Nice’s midday cannon since 1992, through his family fireworks business, Azur Fêtes. It’s a ritual that takes many first-time visitors by surprise, but for locals, the boom at noon is an indispensable cue to step away from their tools, tasks, or computers, and pick up their forks.

“For me, the cannon means that it’s time to get ready for lunch,” explains Anthony Lannerretonne, a photographer who has lived in the city for 29 years. “It’s a reminder to find somewhere to sit down and to raise a glass of fresh rosé to my lips and grab a pissaladière or piece of socca,” he continues. Both of these street foods are classic niçois, a word that means distinctively from Nice.

It is commonly said that one particularly punctual lord, Sir Thomas Coventry, created the lunchtime cannon after growing tired of waiting for his wife to return from social engagements. But scholarly research undertaken by Judit Kiraly, of the Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis, suggested in June 2020* that this is little more than folklore. Kiraly argues that the real Thomas Coventry was not from nobility, but from a respected family in Buckinghamshire, England. A lawyer by profession, he had a passion for astronomy. Coventry first financed the cannon in 1861.

“He was irritated about the church bells ringing midday at different times all over Nice,” writes Kiraly in an email. “By measuring the position of the sun over Nice, he established the true moment of midday.” He may have been inspired by a similar practice from the British Isles: Edinburgh Castle still fires a gun at one in the afternoon, for ships in the Firth of Forth. (Rome also has a midday cannon tradition.) Coventry died in the city in 1869, and without his patronage the firing of the cannon stopped. But six years after his death, the municipality voted in a decree to perpetuate the tradition.

Today, Castle Hill contains few markers of the area’s history, from the arrival of the Greeks in the third century B.C. to the destruction of its once-impregnable citadel by Louis XIV’s soldiers in the early-18th century. A leafy public garden has sprung up in its place, and at 300 feet above sea level, it offers a panoramic view across the terracotta rooftops of Vieux Nice, or old town, toward the Promenade des Anglais and Baie des Anges beyond.

The modern-day midday cannon is not an elaborate ritual, and is not in fact a cannon at all—it was replaced in 1886 by a firework. “It’s colorless, so there are no streaks of gold, red, or blue,” Arnello says. (There are exceptions: For heritage days and other special celebrations, Arnello and a small cast of actors sometimes reenact the firing of the original cannon in full period costume.) His designated space, which is technically part of the police department and is flanked by the Israelite Cemetery, is more utilitarian than decorative—a place to park council vehicles and let off small pyrotechnics.

But that doesn’t mean there’s no show. As the church bells start to chime for noon in the narrow streets of the old town below, he lights the fuse of a small 5.6-ounce bundle of gunpowder. The first boom can only be heard by those present; seconds later another, louder explosion reaches all but the outermost edges of the city. A plume of white smoke rises sky-high, resting for a brief moment before being swept away by the wind.

Arnello only lingers after midday on days when he has company. “Sometimes people call the town hall, other times they hear the noise one day and come looking for me the next,” he explains. He can also be contacted through his business. Whatever way he’s found, he says he is always happy for the audience.

“In almost 30 years, I’ve only been late twice,” he says. However, there are two days of the year when he breaks with his own tradition. On July 14—Bastille Day—the cannon stays silent to honor the 86 victims of the 2016 Nice terror attack. And on April 1, he likes to mix things up. “I usually let it off at 11 a.m., but now people expect that, so it’s no longer a surprise,” he says with a mischievous grin. “Maybe next year it will be at 1 p.m., who knows?”

France’s COVID-19 lockdown lasted 56 days, which was Arnello’s longest-ever stretch away from the post. He says that the local newspaper, Nice Matin, was inundated with calls from residents, who wanted to know why the cannon was deemed a nonessential service. “I also had friends messaging to tell me that, since I stopped lighting the cannon, they were no longer remembering to eat lunch,” he says with a laugh. “This niçois custom has existed for 150 years and I am very proud to play a part in continuing it.”

* Update 9/20/20: This story was updated to reflect recent historical research into Thomas Coventry, who helped create Nice’s midday cannon tradition.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook