Why Doomsayers Think the Eclipse Will Bring Disaster to Illinois

The town of Carbondale sits in the middle of an astronomical crossroads.

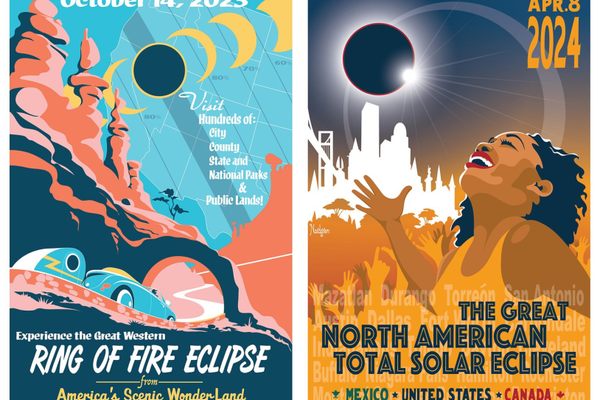

The end of the world will occur in Carbondale, Illinois. That is one of the latest conspiracy theories that’s been floating around the internet over the past year. Seven years ago, this small town experienced a total solar eclipse, the path of which spanned the United States diagonally from South Carolina to Oregon. This year on April 8, the U.S. is once again seeing a band of 100 percent totality, but this time stretching from Texas to Maine. If the paths from both the 2017 and 2024 total solar eclipses were laid on top of each other, the two trajectories would form an X over the country. Carbondale sits right at the center of that X, one of the very few lucky places to see a total eclipse twice in seven years.

“If you lived forever, and you never moved from where you are today, on average, you would have to wait 400 years for a total eclipse to come across where you are,” says Frank Close, Professor of Physics at Oxford University and a Fellow of Exeter College. The likelihood that you could experience two total solar eclipses in one place in the space of seven years is miniscule. The chances are so low, that some believe something special is going on in Carbondale. In particular, conspiracy theorists believe that a seismic event will be triggered when the eclipse arrives in this part of the state, known as Little Egypt, killing hundreds of thousands of people.

Conspiracy theories about eclipses are not new. They also sprung up about the 2017 eclipse, when a prominent Christian eschatologist named David Meade stated that the eclipse was a signal that Nibiru, a small (and non-existent) planet, would crash into the Earth. This year’s batch of theories have been fueled by the film Leave the World Behind. In it, a lunar eclipse looms on the screen, which follows a scene showing a newscast map of a cyberattack across the continental United States. Despite the fact that it shows a lunar—not solar—eclipse, some believe that it’s not just a movie, but rather a warning leading to one conclusion: The 2024 total solar eclipse passing across the United States portends an apocalypse, a mass human sacrifice event.

Conspiracies often arise as an “answer to the disenchantment of the world,” according to Michael Butter, Professor of American Literary and Cultural History at the University of Tübingen. Such theories “perform certain functions for people. They give them back a certain amount of control, because on a higher level, they can at least claim to understand what is happening and what they think is harming them. It also helps them to deal with a feeling of powerlessness.” Butter also proposes that, without widely held beliefs in a god, many people search for higher powers that are in control, for better or for worse.

Apocalyptic beliefs about eclipses are also an ancient phenomenon. One of the most dramatic comes from Norse mythology, with the story of the relentless pursuit of the sun and moon by two wolves called Sköll and Hati. As the story goes, if Sköll catches the sun goddess Sól, who is perpetually fleeing in her chariot, he eats her; this portends the beginning of Ragnarök, the end of the world. During solar eclipses, people would make loud sounds to try to scare Sköll away from eating Sól, hoping to frighten him into dropping her from his jaws.

Mayan groups, including the Yucatec, Lacandón, and Ch’orti’, also believed that solar eclipses signaled the end of the world, and that either spirits of the dead or jaguars would emerge and devour everyone on earth. People reacted with chanting, human sacrifices, war cries, and the killing of any captives, in the hope that the catastrophe could be prevented. Even more recently, an eclipse in 1878 prompted fears of Armageddon in the United States, with many people believing it was the second coming of Jesus and therefore Judgment Day. One man went home, killed his family with an ax, and killed himself for fear of what would happen.

Kate Russo, psychologist and eclipse-chaser, explains that the difference between historical beliefs about eclipses and modern-day conspiracy theories is that myths from ancient cultures came from directly witnessing a solar eclipse and the collective storytelling that emerged from that awe-filled experience. When these stories developed, the scientific information we have today was simply not available, and people needed a way to make sense of what had happened. The creation of conspiracy theories both locally and globally today do not necessarily come from having witnessed an eclipse at all, and may instead relate to a distrust of the state, the elite, or a general feeling of lack of power.

There’s a lot that can be explained surrounding today’s conspiracies about Carbondale. The crossroads position of the town in two eclipse pathways is not unheard of. Total solar eclipses occur every two to four years, and each time, the path of totality hits a different part of the Earth. Those paths occasionally crisscross and form an X-shaped pattern across the globe.

Because the Earth’s axis is on a tilt, and the Moon’s orbit is also on a slight tilt, total solar eclipses only happen when the Moon’s position is precisely aligned with the Sun. The shadow of that eclipse then tracks across the Earth and hits different countries and oceans at varying latitudes and angles each time, depending on the tilt of both bodies and the spin of Earth when the alignment takes place.

The X patterns essentially happen because of repetition over the years, where each eclipse traces a different path due to slight adjustments between the positions of the Moon, Earth, and Sun. Solar eclipses follow a pattern that repeats every 18 years (which is the time it takes for the three bodies to return to approximately the same relative geometry); this is called a Saros cycle. Each eclipse in one Saros cycle occurs slightly more West and South than the previous year, because the Earth is at a slightly different tilt and spin each time. But there are different Saros cycles, since there’s more than one position in which the Moon, Earth, and Sun can align to make an eclipse happen. That means all the slightly different-angled Saros cycles are bound to criss-cross over previous eclipse pathways sooner or later.

Many of these crossovers happen over water, uninhabited areas, or in many cases, simply not in the United States. Turkey experienced an eclipse in the same place in 1999 and 2006, and the next X will occur over the Pacific ocean. It is only when they make their way into the mass media and popular consciousness that conspiracy theories have the material to take root.

The association between eclipses and earthquakes is also not new. The Greek historian Thucydides was the first to suggest in the fourth century BC that tremors could be triggered by the astronomical event. Today, the proposed connection has even been studied by seismologists. One study from 2016 found that large earthquakes do have a slightly higher likelihood of occurring during the full moon or new moon—times at which tidal pull is at its greatest. However, the effect is tiny and says nothing about an eclipse specifically. Other studies find no relationship between the celestial phenomenon and natural disasters. “Earthquakes happen a lot, and many other disasters,” says Close. “If you lumped all disasters and things together, one or two are bound to overlap with an eclipse.” He also points out, “if eclipses happen without disasters, is that significant, or would [conspiracy theorists] just ignore it?”

Bob Baer, a physicist at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, has heard quite a few doomsday predictions surrounding his home, but he focuses on promoting the science of the event. What he can say for sure is happening in Carbondale this year includes a number of informative talks and celebrations. Baer is part of the public astronomy observation program, which trains interested people in the science of astronomy. In particular, this year he is working with the Dynamic Eclipse Broadcast Initiative, a citizen-science project aiming to take numerous photographs of the eclipse. Citizen scientist volunteers are prepared with telescopes along the path of totality, ready to collect imagery that can be captured at no other time.

The moment during the eclipse is so special, Baer explains, because normally when “the light from the sun is hitting all these dust particles in the atmosphere, and light scatters all over the place,” the sun’s corona cannot be seen. During a total eclipse, the sun’s light is blocked, and the corona is visible. By studying the corona through these pictures, astronomers can learn about the sun’s magnetic field, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections, some of which can cause problems with telecommunication systems here on Earth.

In 2017, Baer saw a lot of hype and even anxiety arise about the total solar eclipse, but not because of fears of the apocalypse. With so many people descending upon such a small town, Baer says that people were “panicked about the planning and how the infrastructure was going to hold up.” The US Government Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency released a document noting that, in 2017, “several small communities were overwhelmed in the transportation, communications, and emergency services sector” due to the large eclipse-watching crowds, so it suggested management approaches for 2024. As a result, this year some states have called in the National Guard in to support them, a request that has thrown fuel on the fire of conspiracy. Despite necessary precautions and crowd-management, Baer explains that experiencing the eclipse in Carbondale tends to be more of a “positive, very unifying event,” with broadcasts in the stadium, an airforce flyover, and performances on the field planned for this year.

Whether viewers of the eclipse have photographs, coronas, or doom on their minds, there’s one thing Close recommends paying particular attention to if witnessing the eclipse this year. He says there’s a special moment in the final three minutes of totality that people can look for if they are prepared. “At the moment the sun reappears, look away and look to the east, because the shadow of the moon will be heading off at a thousand miles an hour,” he explains. “The contrast between light and dark is very good, and as daylight returns, you can see the shadow of the moon—gone. It’s as if the riders of the apocalypse have been through the city, and you see that they’ve left you behind. You’ve survived.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook