The 18th-Century Phenomenon of Putting a Filter on a Sunset for Likes

Before Instagram, there was the Claude glass.

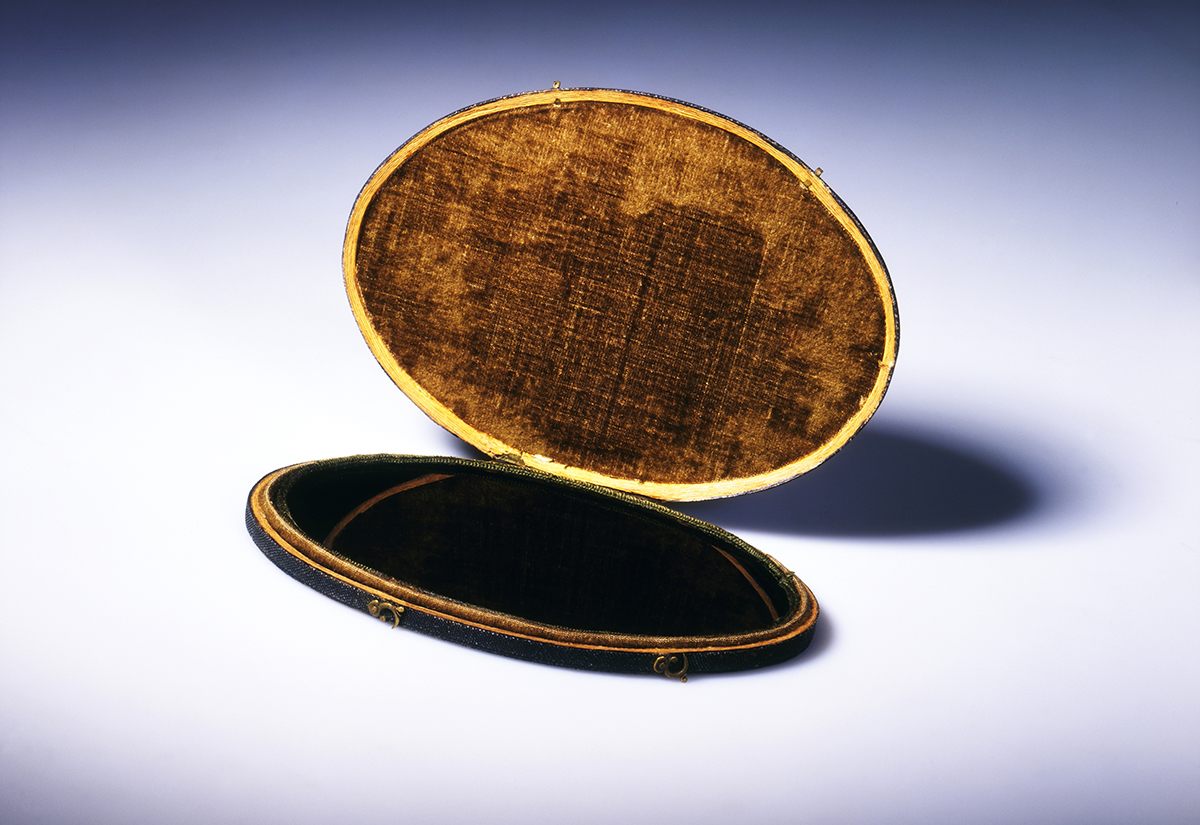

On a mild summer evening in 1769, English poet Thomas Gray found the perfect spot to watch the sun set over the Lake District in the country’s northwest—and he didn’t come empty-handed. As warm light brushed the sky with color, he carefully positioned his Claude glass, a convex, tinted mirror designed to soften and frame the landscape.

Gray’s depiction of that evening in his memoirs sounds a lot like a modern-day selfie accident. With his focus on the mirrored image, Gray said he “fell down on my back across a dirty lane with the glass open in one hand.” In a deft 18th-century #humblebrag, he added that he “broke only my knuckles, staid nevertheless, and saw the sun set in all its glory.”

Thomas Gray was an early adopter, but the Claude glass became a staple of 18th-century packing lists. Portable and compact, it was named for the French artist Claude Lorrain, whose paintings have a beatific glow reminiscent of a heavy-handed Instagram filter.

To use the mirror, travelers sat with their backs to the scene, holding the folding glass at shoulder height so they could see behind them. The convex shape brushed background objects into the far distance, and the tinted glass softened the reflected tones. Users loved how the Claude glass made landscapes look like a Lorrain canvas, with no paint required. But Claude glasses provided more than an artsy filter—they were part of an aesthetic movement that was changing British travel.

Wealthy travelers had been making the “grand tour” of Europe since the mid 17th-century, and while they wrote glowing letters about the beauty of Tuscan landscapes, untamed nature still inspired fear. Wild mountains, Alpine passes, and even the rolling terrain of the Lake District were “sublime,” a word that conveyed real danger and awe. What they called “beauty” was milder and cultivated, reflecting a value for the soft, smooth, and delicate.

Then in a 1768 essay, artist William Gilpin outlined a set of “principles of picturesque beauty,” which Gilpin placed at the intersection of the sublime and the beautiful. The picturesque was rugged nature tempered by milder elements—like a landscape scene offset by a pretty cottage, or the Instagram credo of “little person, big landscape”. And to make an appealing view even more picturesque, Gilpin encouraged the use of a Claude glass.

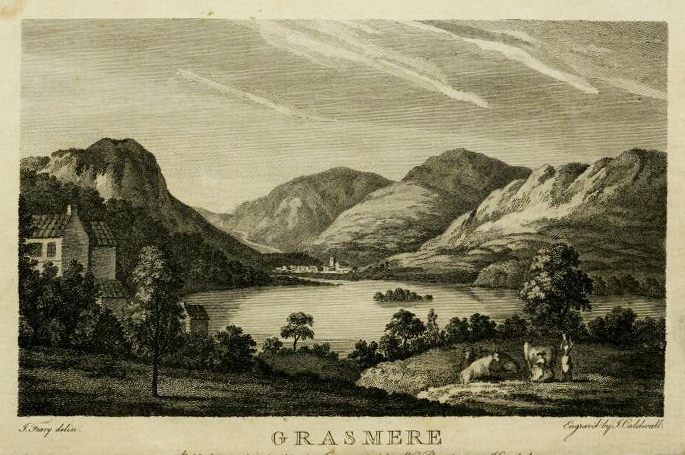

With “picturesque” trending, the Lake District was suddenly on the travel map. Just decades before, the region had been considered too “sublime” for a good vacation. But the rise of picturesque travel put the spotlight on the area, and gave rise to a series of travel guides that detailed the precise locations that travelers could find real-deal, authentic picturesque views (don’t forget your Claude glass!).

Thomas Gray’s memoirs included detailed descriptions of the best vistas in the Lake District, and in the 1778 book Guide to the Lakes, Thomas West directed travelers to the best “stations,” curated sites with Claude glass-ready views. Then, as now, a favorite destination was Lake Windermere, where West’s seven stations became favorite gathering points for fashionable travelers.

It wasn’t long before this travel movement took a meta twist. Because once you go in search of the picturesque, the temptation to futz around with the layout can be overwhelming. In his Observations, relative chiefly to picturesque beauty, made in the year 1772, William Gilpin recalled a trip from Hawick to Selkirk, where the skyline was in clear need of a stylist. “The mountains formed beautiful lines,” he wrote, but “they require the drapery of a little wood to break the simplicity of their shapes.”

As historian Lynne Withey recounted in her book Grand Tours and Cook’s Tours, plenty of 18th-century travelers piped in with recommendations for sprucing up the landscape, from trimming the trees to carving steps into rocky paths. Gilpin himself fantasized about improvements to the centuries-old Tintern Abbey, saying “a mallet judiciously used… might be of service” in removing the abbey’s gable ends, “which are not only disagreeable in themselves, but confound the perspective.”

Imagine the scene: the rural, wild Lake District became a favorite destination for travelers wielding tinted mirrors and guidebooks, full of tips on improving the neighborhood. It was only a matter of time before they became the butt of jokes by everyone from Jane Austen to William Wordsworth.

Some lines could be pulled fresh from a modern-day critique of Instagram-obsessed travelers. In the 1798 comic opera The Lakers, tourist Beccabunga Veronique is hard at work on a painting that corrects the flaws of the Lake District’s all-too-real landscape. “If it is not like what it is,” she said, “it is like what it ought to be. I have only made it picturesque.”

Wordsworth, a shade-throwing resident of the Lake District, entitled one poem “On Seeing Some Tourists of the Lakes Pass By Reading; a Practice Very Common,” then griped at the distracted visitors: “For this came ye hither? is this your delight?” He frequently complained about the mindless tourists that crowded his favorite spots, and rolled his literary eyes about the use of Claude glasses.

And in 1812, Claude glasses and picturesque travel took a satirical death blow when writer William Combe published The Tour of Doctor Syntax: in search of the picturesque, a parody poem lampooning affected, pretentious tourists. Like William Gilpin and Thomas Gray, Doctor Syntax risked everything for a good view and an impressive story—falling in lakes, getting treed by bulls, and being thrown from horses along the way.

“I’ll make a tour—and then I’ll write it. You know well what my pen can do,” said Doctor Syntax to his wife as he set out to get rich and become a travel influencer. “I’ll prose it here, I’ll verse it there, And picturesque it everywhere.” Or as a 21st-century Doctor Syntax would put it: #travel #blessed #picturesque.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook