How Salt Helped Win the Civil War

Southern salt-making operations became prime military targets.

Louisiana’s Avery Island is the ancestral home of Tabasco hot sauce, manufactured there since 1868. But Avery Island isn’t an island at all. Surrounded by marsh, it’s a massive salt dome. That salt sat relatively undisturbed until the Civil War, when it suddenly became a precious commodity.

Salt is easy to overlook today, but before refrigeration, it was essential for preserving food and curing leather, not to mention that a minimum amount of salt is necessary for a healthy diet. Union officials realized early in the war that salt was the key to feeding soldiers and civilians in the South. As soon as southerners built their own facilities to make salt, they became military targets.

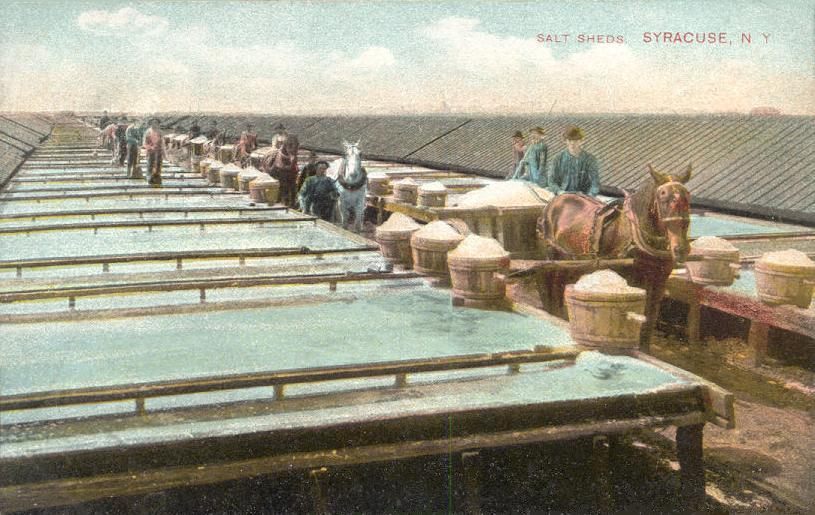

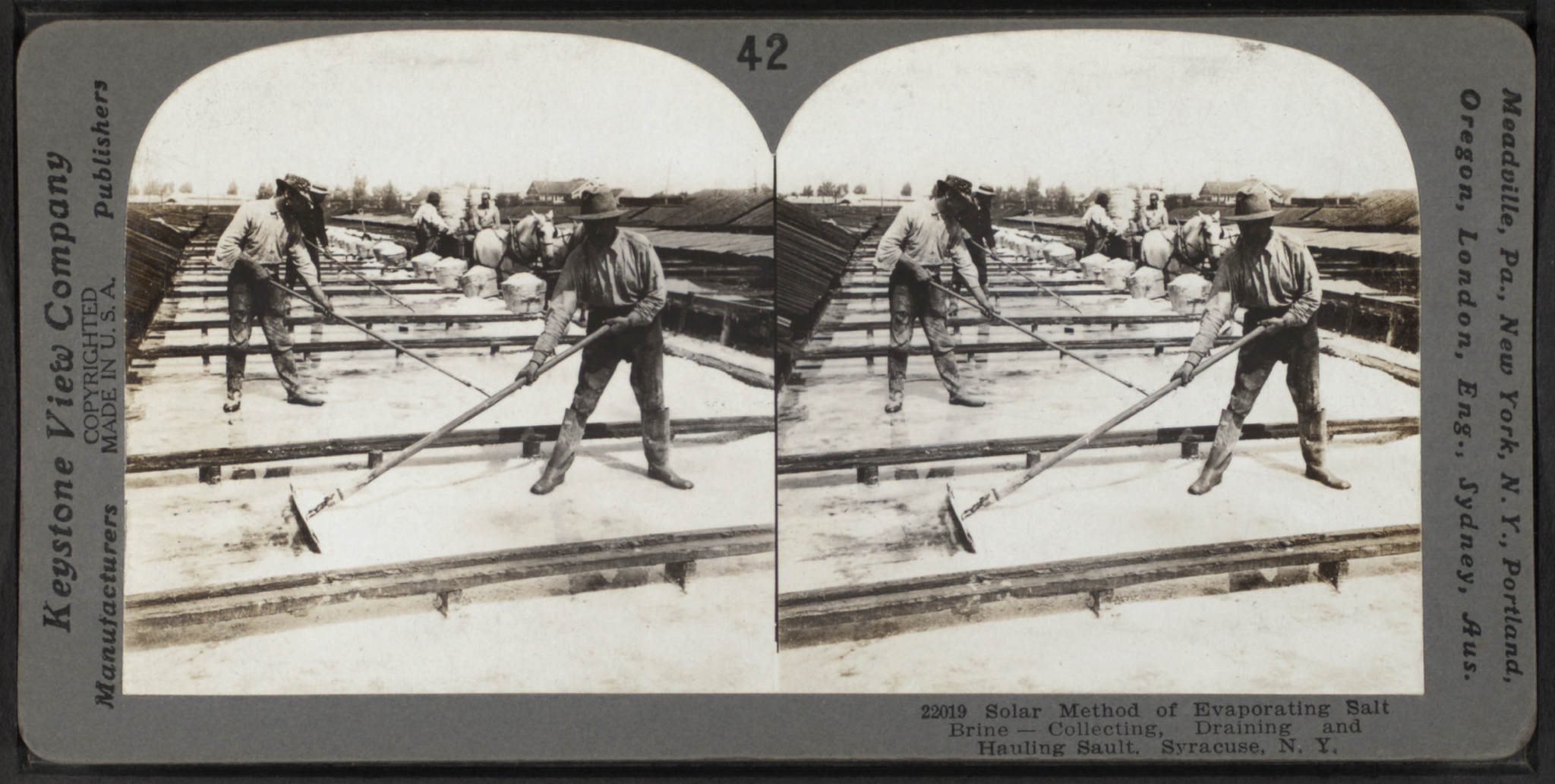

In the 1800s, most American salt production took place in the North. Millions of years ago, an inland sea near Syracuse, New York, gradually filled in with sediment, leaving behind massive salt deposits and brine springs. In 1862 alone, the Onondaga salt works turned these deposits into nine million bushels of salt. Workers pumped water from the salty springs, and boiled and sun-dried it. (Even today, a Central New York specialty consists of potatoes boiled in powerfully salty water, a remnant of when salt workers cooked their lunches in the salt brine.) On the other hand, the South depended on imported salt, much of which was used as ballast when foreign ships came for Southern cotton.

The Civil War began in April 1861, and immediately, the Union blockaded the Confederate states to stall the export of money-making cotton. While scholars debate its ultimate effectiveness, the blockade made staples such as coffee and flour scarce almost immediately. Some imported salt continued to come through the blockade, but it was never enough, not to mention difficult to distribute. Even as recipes for “Confederate Plum Cake” swapped cornmeal for flour, sorghum for sugar, and lard for butter, finding a salt substitute was harder. According to historian Andrew F. Smith, desperate Southerners even re-used salt, by brushing it off their salted meat or boiling it out of the floorboards of smokehouses.

Preserving meat was the biggest problem. Salted beef and pork were staples for soldiers and civilians alike. In the hog-raising South, the situation quickly became dire. The Commissary General of the Confederacy, Lucius B. Northrup, fretted over the lack, writing to another official in 1862 that “in consequence of the insufficient quantity and inferior quality of salt among the inhabitants, much of their meat is spoiling.” Speculation and shipping difficulties compounded the problem. At the beginning of the war, a 200-pound sack of salt in New Orleans cost 50 cents. By 1862, the price was $25.

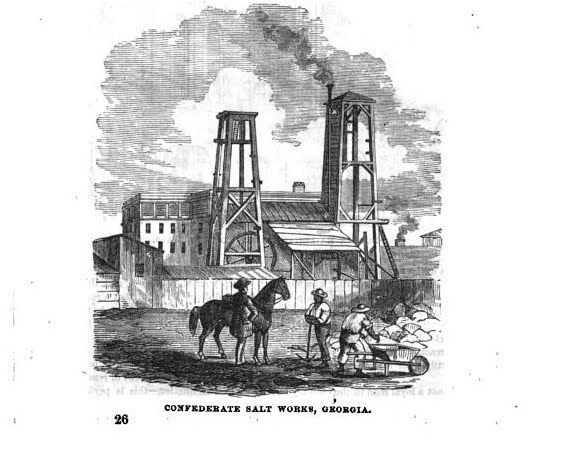

Soon, Southern states offered rewards to those who found and harvested salt. During the Civil War, Avery Island became one of many burgeoning salt works across the South. Salt was so important that many laborers working rock-salt mines and saline wells were exempt from military service. Some workers, though, didn’t have a choice. Many enslaved people, men and women, were forced to labor in the salt works.

Union leaders realized early on that keeping salt from the South could win the war. “What good could it do to destroy salt?” the United States Navy admiral David Dixon Porter asked rhetorically, 20 years after the war. “It was the life of the Confederate army … they could not pack their meats without it. A soldier with a small piece of boiled beef, six ounces of corn-meal, and four ounces of salt, was provisioned for a three-day march.” Soon, raids on salt works became a matter of course.

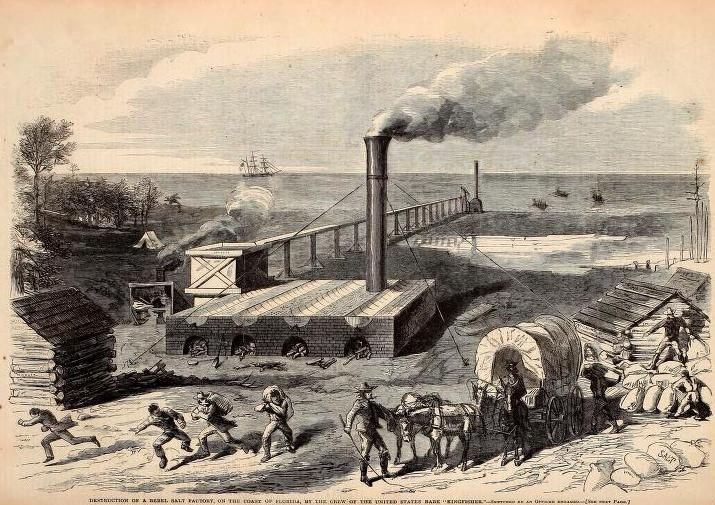

More than once, what led to the downfall of Southern salt works was the bravery of the enslaved, who gave vital information on their location and defenses. In one account of the destruction of a Florida salt works, a group of enslaved men escaped to the U.S. ship Kingfisher. They came with news of a half-finished salt works off of St. Joseph’s Bay. According to the officer recounting the event to Harper’s Magazine in 1862, the ship “sent a flag of truce, and politely informed them they must stop, or we should destroy them.” When the salt-works refused to acknowledge their flag, the Kingfisher fired two shells into the building, then, after it was vacated, disembarked to dismantle it.

It was a huge blow. Historian Adam Wasserman notes that the Confederacy had been depending on a whole winter’s worth of salt for Florida and Georgia from the destroyed site. This made the attack equivalent, perhaps, to taking 20,000 rebel soldiers out of commission. For the rest of the war, fire, gunpowder, and sledgehammers were used to destroy boiling pots and furnaces. Tales abound of the black men and women forced to produce the salt assisting in this destruction. At times, this meant leading Union forces to salt-making cauldrons hidden in swamps. The result was millions of dollars in damage to Confederate facilities, skyrocketing salt prices, and what Southern leaders called a “salt famine.”

The effectiveness of these salt raids was clear to both sides. One sailor, recounting the story of the raid of Darien, Georgia’s salt-works in 1863, wrote, “Salt is a scarce article in the [Confederacy], and the more works destroyed the sooner we shall have peace, for the rebels can’t live without their bacon, and to have bacon they must use salt.” One Southern diarist, the author John Beauchamp Jones, groused in 1862 that “the President [Jefferson Davis] may be a good nation-maker in the eyes of distant statesmen, but he does not seem to be a good salt-maker for the nation.” As for Avery Island, its defenders successfully fended off attack until 1863, when General Nathaniel P. Banks and his men razed its salt works to the ground.

The Union’s strategy culminated with repeated attacks on the aptly-named Saltville, Virginia, which was finally captured in December of 1864. In the words of historian Rick Beard, it was the end of “most of the salt making in the South.” This lack of salt and other supplies was a major factor in the Confederacy’s defeat in the Civil War.

After the Union destroyed Avery Island’s salt works, their former manager, a one-time banker named Edmund McIlhenny, was ruined. Returning to Avery Island years after fleeing Union forces, he had nothing to do but putter around his garden, where he grew some interesting hot peppers. It only took a few years before McIlhenny was using a potato masher and an old Confederate-supply-depot-turned-factory to manufacture tart, spicy Tabasco—seasoned with Avery Island’s salt, of course.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook