Step Inside a Sculpture Garden Made Entirely Out of Trash

Cat food cans, detergent containers, and thousands and thousands of plastic bottles.

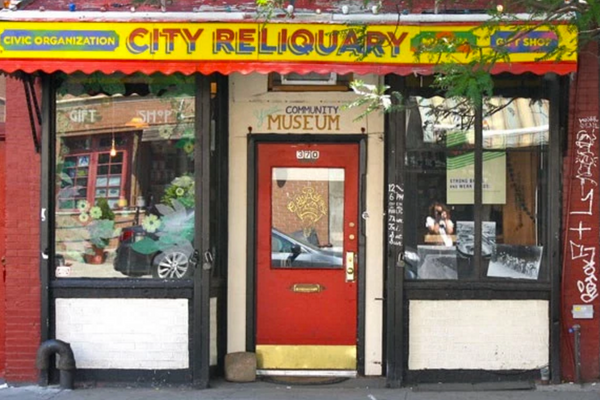

On a chilly spring afternoon, a handful of trash-loving artists hung around the backyard of Brooklyn’s quirky City Reliquary museum, surveying each other’s work and talking about their personal stockpiles of rubbish art supplies.

“I don’t save everything,” said Tyrome Tripoli, who makes large wall installations from deconstructed tricycles and other contraptions. “Most of it goes into the recycle bags.” He gestured up into a tree, where there was a garland of mangled, brightly colored plastic. “Detergent bottles?”

“That’s a thing I can’t save, either!” said Jeffrey Allen Price, who had crafted bamboo-like stalks from stacks of cat food cans.

“I save the caps,” said Debbie Ullman, who turns old newspaper vending machines into artistic compost bins. Barbara Lubliner, an artist who makes plants and balloon animals out of water bottles and spice containers, has more caps than she could ever need, so she passed some on to Ullman, who promised some to Tripoli. Making art out of garbage, it seems, requires being both selective and generous. “It’s about your space,” Tripoli said. “If you have 10,000 square feet, you’re gonna fill it up.”

Tripoli, Ullman, Lubliner, Price, and other artists have work on view in at the City Reliquary through April 29 as part of NYC Trash! Past, Present, and Future, an exhibition that focuses on how the city has wrangled waste over the years.

They are all part of a long tradition. Modern and contemporary artists have used castoff material, of one sort or another, for over a century. Marcel Duchamp and Jeff Koons brought ordinary urinals and basketballs into art galleries. Tracey Emin displayed the entire contents of her bedroom, from mussed sheets to loose change to stubbed-out cigarettes. Robert Rauschenberg and Kurt Schwitters collaged bits and pieces of garbage onto their canvases and installations. These artists were radically challenging the idea of what art could look like, and which tools and materials an artist could use to make it. “I consider the text of a newspaper, the detail of a photograph, the stitch in a baseball, and the filament in a light bulb as fundamental to the painting as brush stroke or enamel drip of paint,” Rauschenberg wrote in 1956. The artists also leaned on everyday debris as as a way to hold up a mirror to society or themselves.

Garbage or found materials are now not unusual in modern art museums, and more recently art made from trash has been in the service of (sometimes heavy-handed) messages about pollution. A lot of art made from garbage today sets out to sound the alarm about waste entering the oceans, for example. Last summer, Greenpeace worked with the artist John deCaires Taylor on a project called Plasticide, a sculpture of a family enjoying a picnic at the beach—flanked by seagulls vomiting up shards of plastic. It’s a grim scene that depicts a real threat to wildlife. Roughly 1.8 trillion pieces of trash have coalesced into the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, prompting artist Maria Cristina Finucci to issue passports to the mythical, dystopian Garbage Patch State. (We’re all already citizens, whether we have passports or not.)

Some of the artists at the City Reliquary do describe their work as a kind of activism—Ullman’s boxes are meant to normalize composting as a practice—but most of the artists in the show appreciate trash not only as statement but also a material for silliness and surprise. Lubliner’s bottle garden features succulent rosettes made of plastic bottles—both of which are known for storing water. The puns roll on: She called her first balloon-animal-like dog, also made of bottles, Pupsi.

For Lubliner and her fellow artists, scrounging is an engine for creativity. “I think of plastic as a new ‘natural resource’ because it’s just so prevalent,” she says. “Yes, there’s a statement about artificiality and overuse of plastic, but I’m also responding in a creative way, like, ‘Look what we can do with this abundance of trash.’ I respond to what’s around.” She has weaved metal tapestries from leftover circuits from a lighting factory, and fashioned little figures from tubes that once held bolts of fabric.

Price finds it to be a stimulating. creative challenge, too—and one that feels personal because his materials come from his own life. Empty glue tubes, crusty paint brushes, aluminum foil, tea bags, tape—“everything that’s byproduct can be made into art,” he says. Eventually, he hopes to make his supplies available to any artist who wants to come experiment. “We see art everywhere,” he says. “Like, ‘What can we do with this?’”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook