Why Chuck E. Cheese’s Has a Corporate Policy About Destroying Its Mascot’s Head

It doesn’t usually involve sledgehammers in a parking lot.

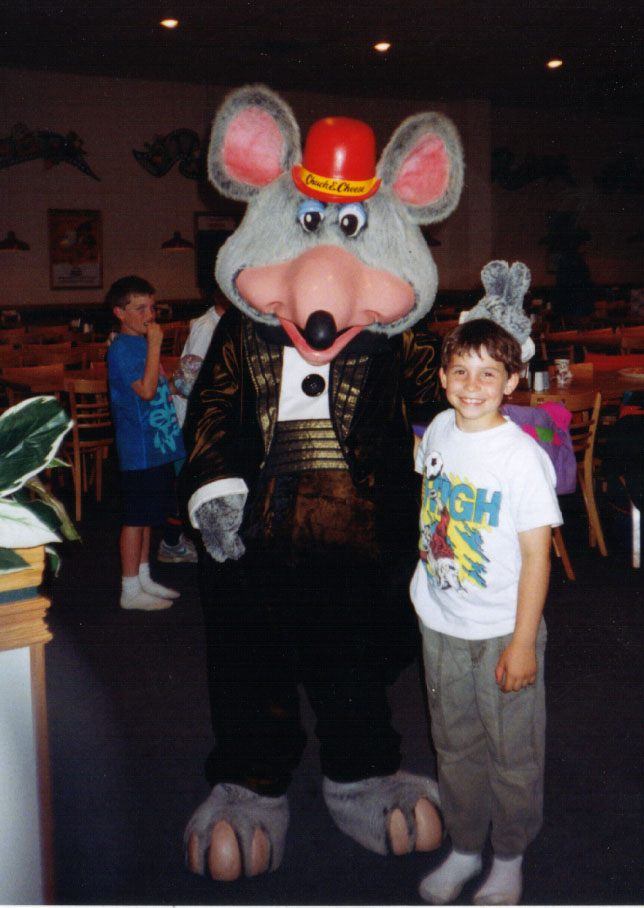

Chuck E. Cheese’s, the combination pizza restaurant and arcade, has been serving up entertainment since it first opened as a “Pizza Time Theatre” in 1977. Early on, its eponymous cartoon character was a cigar-smoking rat from New Jersey. Chuck has since gone through several rebrandings—he’s now a wide-eyed mouse whose full name is Charles Entertainment Cheese—and, starting this year, the restaurant’s animatronic band has retired. Still, the Chuck E. character, which remains a fixture at their many national and international locations, is played by a rotating cast of store employees in costume. They often lead children in conga lines through the restaurant.

Several weeks ago, a local Patch report in Illinois revealed a seemingly disturbing underpinning of the Chuck E. Cheese universe: A former employee told the paper that a company policy required them to demolish branded items, among them the cartoon character’s head, which is part of the costume. A Patch video captured two former employees of the recently-shuttered Oak Lawn location bashing Chuck’s brains in with a sledgehammer.

Why did executives at CEC Entertainment, Inc. establish a policy mandating the destruction of their business’s beloved namesake?

For many current and former employees, the policy is mysterious. “If [kids] saw a random Chuck E. head floating around, that might be a little bit problematic,” offers Loree Stark, a public interest attorney who formerly worked at two locations in Kentucky for several years. “Or maybe there’s some kind of sacrifice involved in order for the grounds where Chuck E. Cheese’s was to not be haunted.”

But Meredith Rose, an intellectual property attorney and a policy advocate, has surmised the policy’s purpose since her brief time working at a Middletown, New Jersey, Chuck E. Cheese’s in high school. “If you own this intellectual property writ large, you don’t want a secondary market to pop up. [You don’t want] people selling animatronic Chuck E.’s on eBay,” says Rose. “So if someone were to set up, say, an entire backyard-like sideshow thing where they replicate the animatronic band and all this swag, it might conceivably be viewed as not exerting control over your trademark.” In a future where the mascot is regularly seen outside Chuck E. Cheese’s, the company could lose the legal right to monopolize the character.

CEC’s reasoning is similar to Rose’s observations, and it reveals how difficult it is to maintain the fantasy of Chuck E. Cheese’s for kids. Brian Dahlke, the company’s Real Estate Manager, says that employees are indeed required to destroy Chuck E.’s head when it’s no longer needed, which often happens when a location closes, or the costume is updated. “Even if the head is past its useful life, our practice is to take all of the parts off the head, so we salvage the nose and the ears and some of the other parts,” he says.

The idea is two-fold: So that no one can find a Chuck E. Cheese costume in a dumpster, and also so that children never see the disembodied head of Chuck E. “Our policy at Chuck E. Cheese’s, for when the stores operate, is to never bring that head out by itself when the store’s operating,” he says. “Because that can be very traumatic for a child.”

Dahlke says that destroying Chuck E. is usually done “out of sight.” In the case of Oak Park, Chuck E.’s head was slated to return to a warehouse in Kansas where games and robots are typically shipped following a store’s closure. “But those employees went rogue and took that outside … they should not have been doing that,” Dahlke says. He is quick to add that most Chuck E. Cheese’s locations don’t keep sledgehammers around, and they appeared in Oak Lawn to break down old furniture. Usually, he says, Chuck E.’s head isn’t bashed in. Instead, stores will slice it in half or otherwise “find a way to make sure that it’s not recognizable.”

Why not just ship Chuck’s head to another restaurant? Former employees say that the Chuck E. costume isn’t built for survival, and the matted fur costumes get a lot of use. “By the time they close down a Chuck E. Cheese’s, those things have been used for a couple of years,” says Rose. “And if the frequency of not cleaning them is still the norm, then I wouldn’t want to have anyone else set foot in that.”

While most former Chuck E. Cheese’s employees are unaware of the corporate destruction policy, they say the measure supports the store’s stringent rules surrounding the character. “A lot of the training I had at Chuck E. Cheese’s was sort of [like] how you hear about Disney making the magic and stuff like that. It’s all about keeping up that image,” says Louis Micheli, an NPR revenue accountant who worked at two Chuck E. Cheese’s locations in Pennsylvania.

“I do remember they were very keen on maintaining the Chuck E. image,” says Georgia Davidson, who worked at the Johnson City, New York*, location during the summer of 1983. That meant “no talking in costume … even if a kid with a Bic lighter runs up to you asking ‘Does Chucky burn?’”

Employees have innumerable other examples of struggling to maintain the mascot’s innocent, kid-friendly image. One former Chuck E. Cheese’s General Manager recalls a group of kids storming the stage where the animatronic band played. “They got up onstage, and before I could get up there and tell them to get off, they had taken all the clothes off Chuck E.’s outfit, off the robotic body,” she says. “And kids were screaming because it was just a cyborg with a Chuck E. head.” Fun has often turned to mania at Chuck E. Cheese’s, which has a well-documented history of brawls. The former manager says that she “had the police on speed-dial, because the fights in the store were through the roof … [Anarchy] is a really good word to use for Chuck E. Cheese’s.”

What was perhaps hardest for costumed employees about keeping the magic of Chuck E. Cheese’s alive, though, happened when kids’ curiosities got the better of them. “Honestly, sometimes it was really fun to be in the costume because you got to dance and throw some tickets up into the air,” says Micheli. “And sometimes you get kids in their karate outfits who want to show Chuck E. how strong they can kick, and you just get kneed in the shins.”

*Correction: This post previously stated that Georgia Davidson worked at the Chuck E. Cheese’s in Johnson City, Tennessee. She worked at the Johnson City, New York location.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook