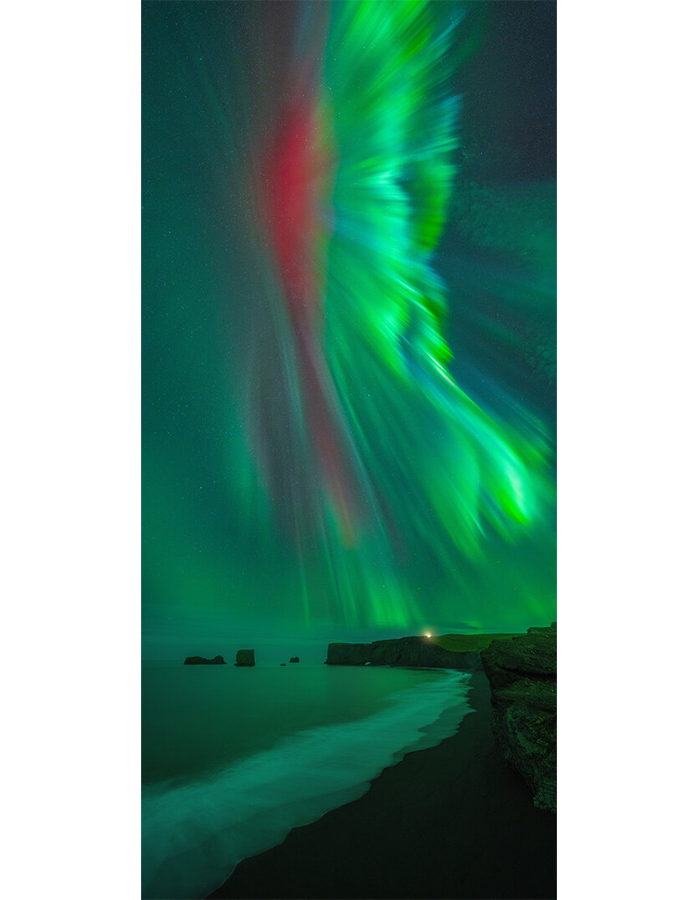

Aurora Hunters Capture the Wonder of the Northern (and Southern) Lights

A curated collection of images shows why this natural phenomenon has fascinated and inspired humans for millennia.

Across the Arctic, people have revered—and sometimes feared—eerie, shifting lights that arrived without warning in the night sky and never appeared the same way twice. Ancient explanations for the lights vary widely among the Saami, Tlingit, Vikings, and other northern cultures, changing from one fjord to the next and over centuries. The aurora borealis, or northern lights, have been described as the spirits of women who never married or of the stillborn; as restless, lonely souls of those who died from suicide or murder; as reflections glinting off the armor of fierce Valkyries; as malevolent spirits who might chop off your head if you whistled at them too loudly. Regardless of how they were explained, it appears that everyone who witnessed the lights was filled with wonder and the need to understand the phenomenon.

The first known documentation of auroras was more than 4,500 years ago in China, but some archaeologists have interpreted much older cave art as depictions of prehistoric auroral displays in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Auroras occur near both poles, but are more commonly reported in northern high latitudes simply because most humans—more than 80 percent—live north of the equator.

Science has since sorted out most of the details about what auroras really are. Charged particles borne on a solar wind smack into Earth’s magnetic field and transfer their energy to oxygen and nitrogen in our upper atmosphere. The explosive process creates brief bursts of light, typically green and sometimes red (both from oxygen) and less commonly blue (from nitrogen), in regions near but not at the geomagnetic poles. (The exact area where auroras are visible, a band known as the auroral oval, fluctuates based on solar wind activity and shifts in the magnetic field, which also affect how individual auroras appear.) While the origin of auroras is no longer a mystery, these elusive, hauntingly beautiful phenomena still mesmerize anyone fortunate enough to see them.

Thanks to dedicated, aurora-chasing photographers, all of us can get a glimpse of these dancers in the sky. The travel photography blog Capture the Atlas (not affiliated with Atlas Obscura) recently announced their fifth annual curated Northern Lights Photographer of the Year collection, sharing dozens of images—of both northern and southern lights—that capture auroras in all their glory. Here are a few of our favorites.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook