In Ancient Egypt, Jar Burials May Have Helped the Dead Be Reborn in the Afterlife

First found at the ancient fortress of Tell el-Retaba, child burials in ceramic jars perplexed early archaeologists.

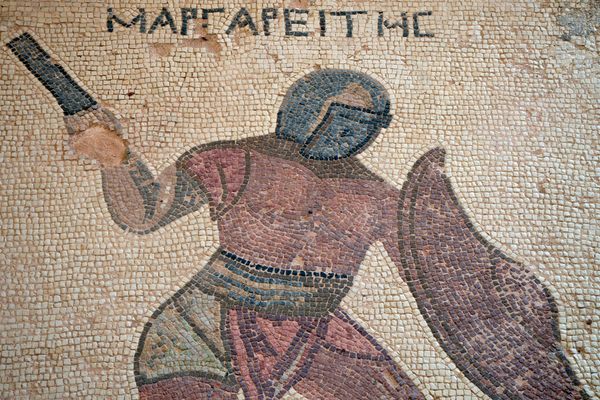

When journeying northeast from Cairo, a traveler will eventually reach the geographical line which sharply divides the Nile Delta and the Sinai. This is where the verdant fields of grain, little irrigation ditches, and thick loamy soil give way to the arid desert of the peninsula. Outcroppings of limestone, tempered with fragments of ancient fossils, and driving sands characterize the region. This border region hosted the impressive fortress of Tell el-Retaba, fortified and expanded more than 3,000 years ago during the reign of Egypt’s militaristically minded pharaoh, Ramesses the Great. The fortress was one of several that formed a formidable defense network along the north coast of the Sinai Peninsula. This chain of fortresses was known in ancient times as the Ways of Horus, and was used by the Egyptian army on its way to fight Pharaoh’s enemies across the Near East.

But Tell el-Retaba did not just house soldiers, it was also home to their families. While conducting excavations at Tell el-Retaba in the early 20th century, British archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie found a curious burial. It was not located in the dedicated cemetery, outside the fortress, but rather cut into one of its actual mudbrick walls. The burial contained an infant, possibly less than a year old, whose body had been placed inside a ceramic amphora, a type of storage jar.

Unfortunately, but also rather typically of archaeologists of the era, Petrie responded to the find by constructing a rather imaginative narrative: He claimed the pot burial was evidence of both human sacrifice and non-Egyptian occupation of the site (in the minds of Victorian archaeologists such as Petrie, ancient Egypt was simply too civilized to have practiced such a brutal tradition). Petrie was wrong on both counts. The ancient Egyptians did, at one time, practice human sacrifice, and the pot burial was not evidence of any non-Egyptian occupation; many more such interments would be found throughout Egypt.

In pot burials, also called jar burials, the body is interred in either recycled or purpose-made ceramic containers. And the ancient Egyptians were not the only civilization to use them. Such practices are found from ancient traditions in the Philippines and Malaysia to Japan’s prehistoric Jomon period, to third-century burials in Iran, and similar customs on Corsica that lasted until the sixth century.

Petrie may have been the first archaeologist to find a pot burial at Tell el-Retaba, but he was far from the last. Excavations conducted by other teams at the site located more pot burials of young children. Across Egypt, hundreds of pot burials, containing the bodies of both children and adults, have been found from the Predynastic, about 6,000 years ago, to the end of the Pharaonic Period around 30 B.C.

Traditionally, scholars have considered these pot burials as a practice of the poorest members of ancient Egyptian society: people who could not afford a wooden coffin and had to resort to repurposing a container used to store wine, olive oil, or pine resin for their loved one’s remains.

However, recent research has suggested that the pot burials were not limited to lower-status individuals. There was a cultural association between pots and the womb, and they may have been chosen as a way to aid the deceased individual’s rebirth into the afterlife. The ovoid shape of these vessels also invokes the idea of an egg, another symbol of rebirth and regeneration in Egyptian mythology.

During the reign of Ramesses the Great, about the time the infant was buried at Tell el-Retaba, a popular style of coffin emerged in Egypt, which is distinguished by being made entirely out of clay. Known as slipper coffins, they did not impress early archaeologists, such as British Egyptologist William Perry, who dismissed them as having been used only by “poor people”—even though they would have required both significant skill and resources to create. The fuel alone needed to fire a full-size human coffin made entirely from clay would have been considerable, particularly in Egypt, where trees and timber for burning were always scarce.

In fact, what connects recycled pots and amphorae used in burials with purpose-made slipper coffins is not who used them, but the clay they were made from.

Egyptian clay, used for making both pots and coffins, came in two varieties: Nile silt clay gathered from the river’s banks, from which most Egyptian jars and the slipper coffins were made, and Marl clay, mined in the desert and used primarily for certain types of amphorae. Some pottery vessels were even made from a mixture of these two types of clay. Throughout the Pharaonic era, clay and mud were associated with rebirth and regeneration, perhaps inspired by the black silt mud of the Nile, which fertilized Egypt’s fields every year, nourishing crops and feeding the country. The goddess Taweret, associated with birth and rebirth, was depicted as a hippopotamus due to the association of this animal with the black mud of the river. The god Khnum, the divine potter, god of the source of the Nile and lord of created things, fashioned humans out of clay on his potter’s wheel, causing them to come to life.

Given this strong link between clay and birth, it is perhaps not strange that so many ancient Egyptians wanted their remains—including those of their youngest and most precious family members—surrounded by this potent substance as they were placed in their tombs, to begin their long and arduous journey towards the afterlife and their own desired rebirth in the Fields of Reeds.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook