A Jewish Commodore Saved Monticello, And His Family Got Hell for It

The public debate around the Founding Father’s house being in ‘alien hands’.

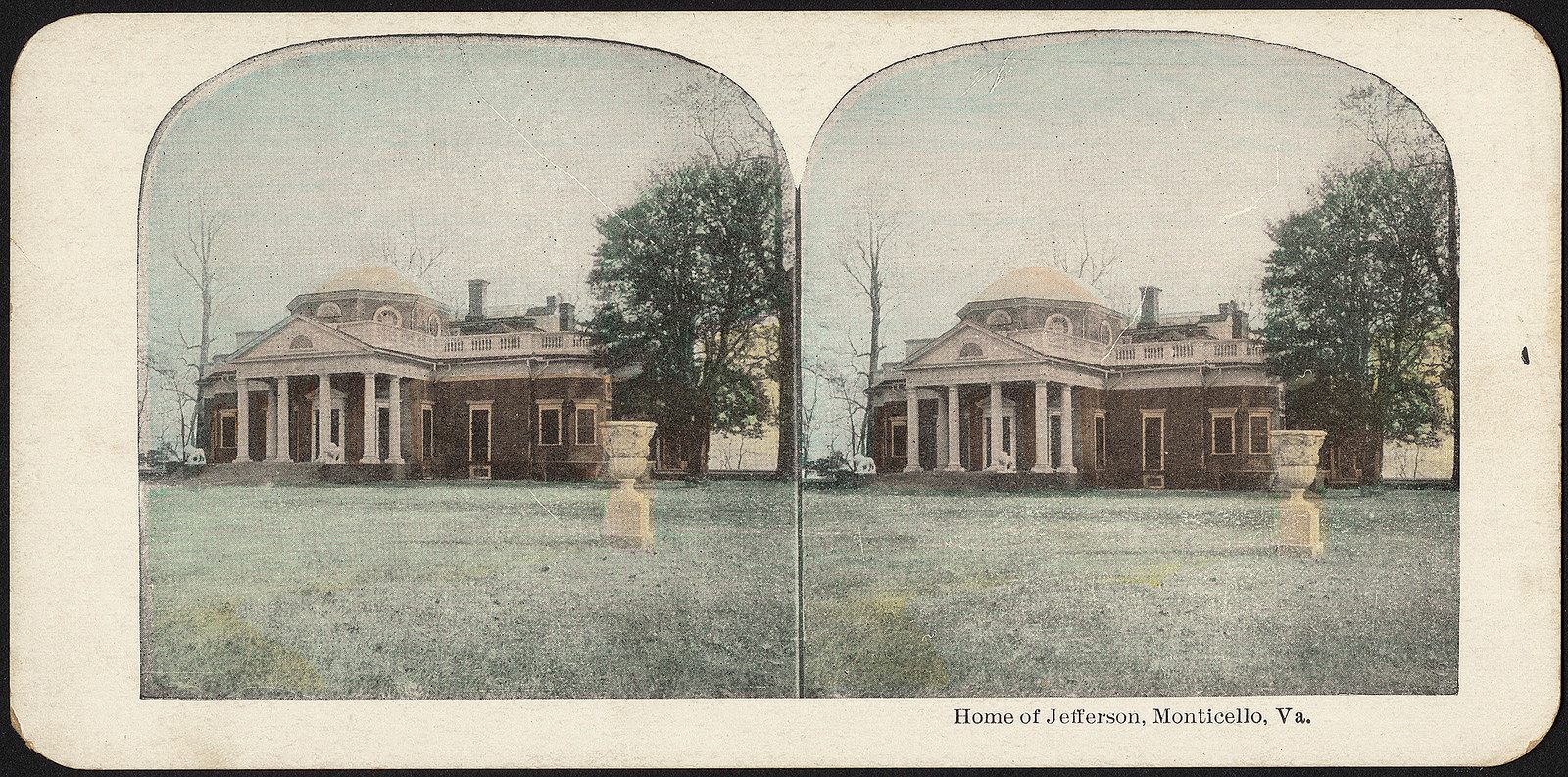

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. (Photo: Martin Falbisoner/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fifty years after Thomas Jefferson died in debt, vines choked the bricks of his 700-acre Virginia farm Monticello. Its famous oaks had been felled, and relic hunters chipped away at his grave.

But Uriah P. Levy really wanted the farm anyway. The first Jewish Commodore in the Navy, he had handled anti-Semitism, and he liked the way Jefferson wrote about American religious tolerance. He had even commissioned a statue of Jefferson in 1834 that lives in the Capitol today.

Levy’s own death in 1862, however, did not secure the future of one of America’s most famous homes. Levy left a complicated will, which imagined Monticello used as a farm school for Navy warrant officers’ orphans. During the Civil War, the Confederacy seized Monticello but after the war, it reverted to the Levy heirs, who disputed its ownership the next 14 years.

What happened next was a now-forgotten decades-long national controversy, adorned with no small measure of anti-Semitism. Jews have been a part of American life in the South since the country’s founding, but have rarely been as visible as the Levys.

Uriah Phillips Levy, commodore of the US Navy. (Photo: US Navy/Public Domain)

By 1879, Monticello was a mess again. When Jefferson Levy—Uriah’s great-nephew—bought Monticello from his relatives, tourists had chiseled off bits of ornamental friezes, cows had lived in the basement, and pigs had dug up the lawns. Levy was a New York lawyer, real estate speculator, and congressman. He added some details, like a brace of stone lions guarding the west portico. He used Monticello as a second home, and hosted grand parties there. His nieces remembered seeing Theodore Roosevelt in the great drawing room.

Also a guest was Maud Littleton, the wife of another New York congressman. “Thomas Jefferson was uppermost in my mind,” she wrote of her night at Monticello. “I could think of no one else. Somehow I had never connected Mr. Levy with Mr. Jefferson and Monticello. He had not entered my dreams.”

Not being in Littleton’s dreams was evidently incendiary, because she decided Levy should not own Monticello. “By what right must the people of the world ask Mr. Levy for permission to visit the grave and home of Thomas Jefferson?” she wrote. “Surely he does not want a whole nation forever crawling at his feet for permission to worship at this shrine of our independence.” Littleton launched a campaign. She circulated petitions, gave speeches, and wrote a pamphlet called “One Wish.”

The statue of Thomas Jefferson that was presented by Uriah Phillips Levy to the Congress in 1834. (Photo: US Capitol/Public Domain)

People took up Levy’s side, too. One was Flora Wilson, who was the daughter of the Secretary of Agriculture. She and Littleton were both suffragists, so Wilson was happy to see Littleton standing up for her cause, even though they disagreed. But when Littleton cried in front of Congress, Wilson shuddered. “Can we ever achieve our purposes employing as does a spoiled child the last resort to get his own way?” she wrote. “I cannot find any evidence of tears dampening Catherine de Medici’s poison potions.”

And Levy spoke up for himself. “Every stone and brick in the home of Jefferson, every tree, every nook and corner, every foot of Monticello is dear to me,” he said. “Mrs. Littleton is a woman,” he said, “and consequently I am not offended, but only hurt, at the criticisms. ” By 1912, Littleton had 10,000 petitions going around. In November of 1912, Levy said, “I spend yearly $10,000 for its upkeep. Visitors are welcome. I see no reason for an organization trying to take from me the home of my forefathers.”

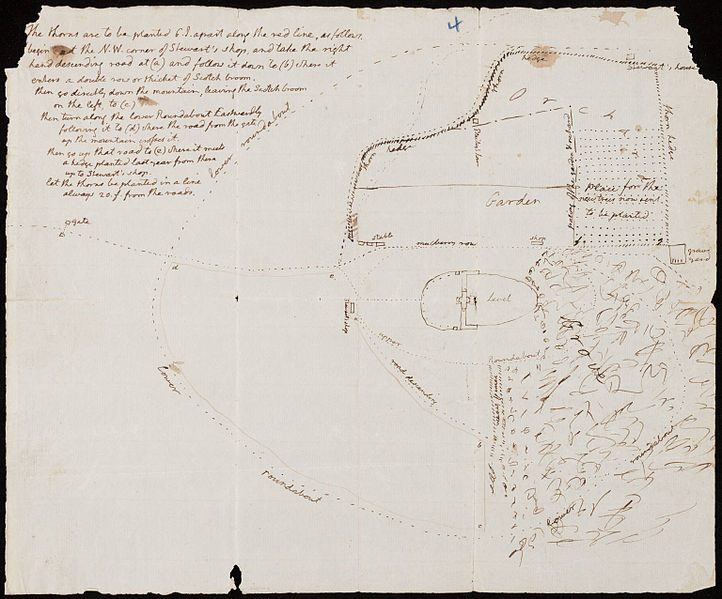

A drawing of the gardens, orchards and grove at Monticello, Albemarle County, Virginia, by Thomas Jefferson, in a letter to J. H. Freeman. (Photo: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University/Public Domain)

“Forefathers nothing!” Littleton told one reporter who came to her house at 113 East 57th Street in New York, and found her in the midst of piles of maps, pamphlets and records, with eight secretaries working at her dining room table. “Mr. Levy is no relation to Thomas Jefferson. He objected to my mentioning everywhere that he is not the grandson of Jefferson on the ground that it had nothing to do with the case.” This despite the fact that Levy hadn’t ever claimed to be Jefferson’s blood relative; his parents named him Jefferson to honor the family hero.

That was the kind of thing that indicated a more sinister presence at work. As Marc Leepson writes in Saving Monticello, much of the anti-Levy campaign “contained more than a whiff of anti-Semitism.” Littleton referred to Jefferson Levy as an Oriental potentate, and wrote that Jefferson’s grave was tainted by Levy’s “ruthless commercialism.” In 1914, popular advice columnist and Littleton partisan Dorothy Dix wrote an article in Good Housekeeping in which she wrote that Monticello was in “alien hands,” after “Captain Levy refused to part with his bargain.”

A stereograph of Monticello. (Photo: Boston Public Library/Public Domain)

Levy responded over the course of Littleton’s drive in ways that ranged from the plaintive—“The property is mine—to the courtly—“This campaign has been attended by numberless and wholly unnecessary misstatements about Monticello, and about my uncle, Commodore Levy—those about myself, I suppose, I must overlook…I have said that I do not expect gratitude, but I think every American will feel that I am entitled to fair play.”

Congress agreed. Despite Littleton’s efforts, no one wrested Monticello from Levy. A bill that would have explored the idea of buying Monticello was defeated in 1912.

But by 1914, Levy, worn down by the financial burden of maintenance and the constant pressure to give in, was willing to consider relinquishing Monticello; secretary of state William Jennings Bryan supported a plan to make it a presidential retreat that he liked. Congressional hearings in 1915 about Monticello’s future demonstrated some softening on both sides. Littleton acknowledged that Levy had done “probably as well as such an exacting public task could be done by an individual.” Monticello never became a retreat, but did end up open to the public. Levy died in 1924, one year after a fund raised by national subscriptions paid him for his property.

Update, 8/4: The story originally had the wrong date of Uriah Levy’s death. We also clarified that Monticello is open to the public, but managed by a private foundation.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook