100 Wonders: Don Justo’s Self Built Cathedral

What does true belief mean? What is the difference between delusion and the divinely inspired?

Twelve miles north of Madrid in Mejorada del Campo, a 90-year-old man is working to finish his life’s work: a grand cathedral. It is a cathedral with no trained architect, no government approval and no benediction from the Catholic Church. It is either the work of a madman or that of a prophet.

Justo Gallego Martínez was a born a farmer to a very religious Roman Catholic mother. At the age of 10 he saw the effects of the Spanish civil war and witnessed communist forces shooting priests and ransacking the church. This left him with a distrust of government and a desire to enter into the service of the Catholic Church.

As a young Trappist monk in the 1950s, Don Justo fasted more, and worked harder. Too hard. He didn’t fit in. After eight years in the order—and just prior to taking his vows—Don Justo Gallego Martinez was asked to leave the order.

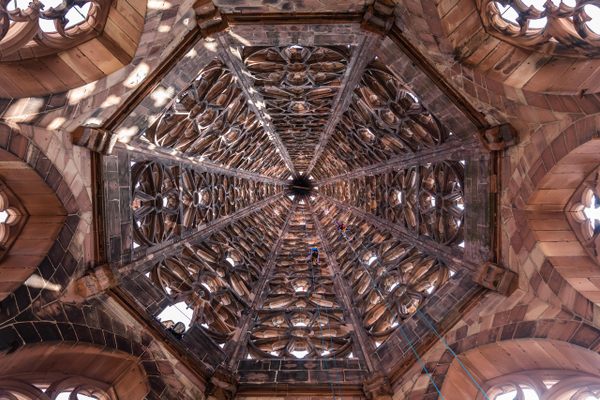

Heartbroken and determined to dedicated his life to God, Don Justo began laying the foundations of a great cathedral with his own hands on a plot of land bequeathed to him by his parents. For the last 55 years, Don Justo has been building this rogue cathedral, which aims to rival St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Everything has been done by hand, and, for the most part, by the hands of Don Justo. The stained glass is made with ground glass and glue. The huge dome is made from plastic food tubs. The pillars are concrete, cast using oil drums.

Today the frame of the cathedral, which has a 131-foot-tall dome modeled on St. Peter’s, towers over the town of Mejorada del Campo. The interior is roughly half the size of a football field. Below the main building there is a crypt, a complex of minor chapels, cloisters, lodgings and a library. The total area of the church is over 86,000 square feet. The entire structure was built without the use of a crane.

Despite being 90 years old, Gallego Martínez usually begins his workday at 6 a.m. and works for 10 hours a day—except on Sundays. Though he worked alone for the first 20 years, he now has help from family and volunteers. Nearly all of the building materials are scavenged or donated. Looking around, one can see columns made of concrete-filled plastic buckets or air ducts and stairs whose lips are formed from coils of wire. Piles of building materials—concrete, brick, rebar, even newspaper—line every wall and fill every nook. Though many of the stairwells are partially blocked by stacks of pipes, it is still possible to get to the roof for the best view of Mejorada del Campo. Don Justo’s full vision for the cathedral includes two narrow spires to reach almost twice as high as the roof of the edifice.

Cathedrals take a long time to build—more than a lifetime. Sometimes more than many lifetimes. It is unlikely Don Justo’s creation will reach completion during the life of its 90-year-old architect. What will happen to the building after Martinez’s death remains an open question. No one has yet stepped up to take over the project.

Given his age, Don Justo expects he will soon be with his maker, to whom he has dedicated his entire life in the form of this massive cathedral. The former monk has said that if he had his life again he would start the cathedral over, but this time would build it twice as big.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook