About

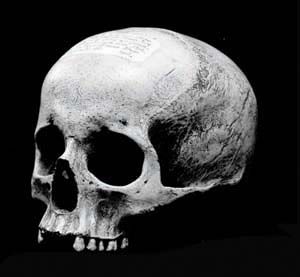

The thing about skulls is that, it can be remarkably hard to prove whose they were.

Of course, one can tell things like gender, age, sometimes history of disease or injury from a skull, therefore making a mismatch easy to identify. But even if all those elements match up, it's still difficult to make a positive match. With the advent of DNA testing, in theory, one should be able to scrape a little bone, run some tests, and voila: definitive proof of skull ownership... Alas, it's not so simple in the real world.

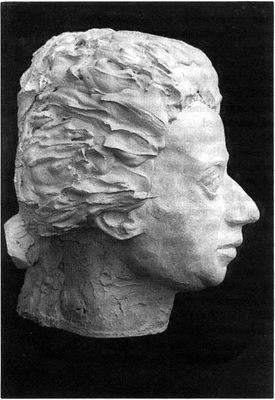

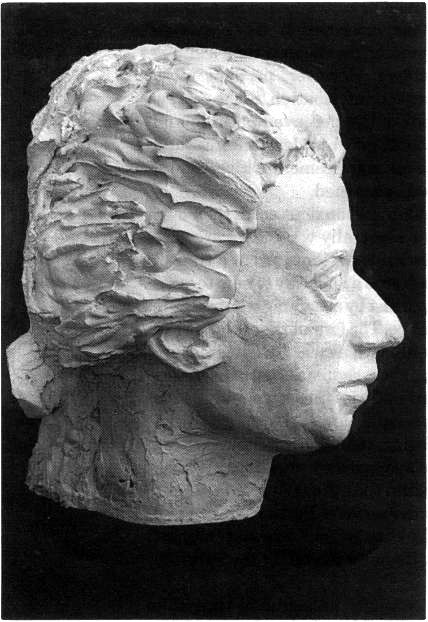

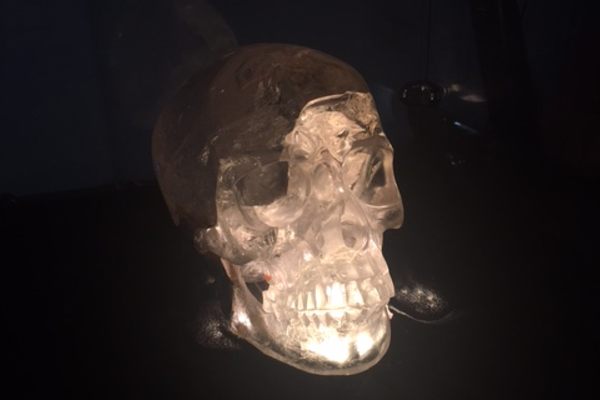

In 1902 the Mozarteum in Salzburg, Austria, came into possession of what was said to be Mozart's skull. Missing its lower jaw, this skull matched a historical record indicating that Joseph Rothmayer, a gravedigger, had taken the skull from the group grave in which Mozart was buried ten years after his death in 1791.

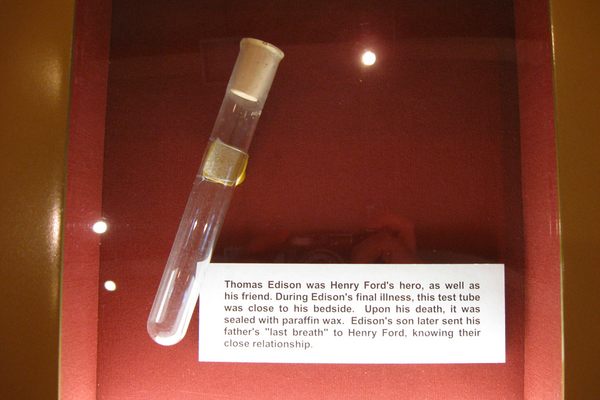

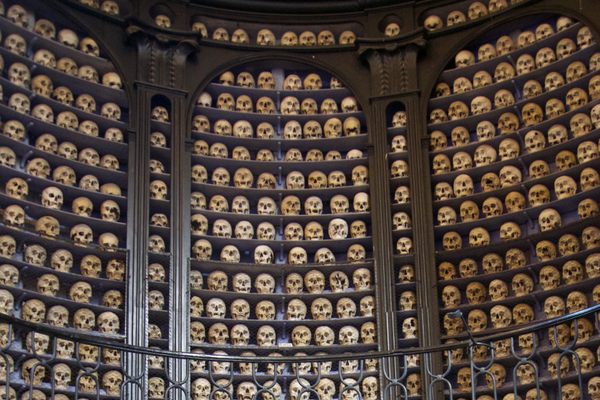

Though often said to be buried in a mass or pauper's grave, Mozart was actually buried in a grave with only four or five other bodies in it, a standard middle class burial procedure in those times. According to the story, the gravedigger attached a wire to the skull so that he'd know which one was Mozart's when he went to retrieve it. (That he would have waited ten years to do so, however, casts some doubt on this claim.) From there, the skull passed through various hands, a sexton, one Dr. Hyrtl's phrenological collection (which, excluding Mozart's skull, would go on to become the Mütter Museum's skull collection) before ending up in the hands of the Mozarteum in 1902.

So it was with great excitement that in 2006, 104 years after acquiring it, the Mozarteum was planning to prove once and for all that it possessed Mozart's skull. The plan was to test the skull's DNA against the DNA of Mozart's relatives, taken from his maternal grandmother and niece's thigh bones. The results were dismaying.

Using mitochondrial DNA, the results suggested that not only was the skull unrelated to the Mozart family's remains, but that the remains were unrelated to each other, casting doubt on the the family remains as well. Due to the confusion, the result was neither negative nor positive, but entirely inconclusive.

Perhaps the best case for the skull's being Mozart's is the fact that the skull shows that it took a hard hit about a year before its owner died. This would be consistent with the headaches that Mozart described in his last year of life and would provide some additional explanation of his early death. But this too is ultimately speculative, and the mystery of Mozart's skull will, for the time being, remains unsolved.

Though still at the Mozarteum, the skull is no longer on display, as it unnerved a number of the docents. However, with an advance request, a showing of the skull may be given.

Related Tags

Published

July 15, 2012

Sources

- http://www.moz.ac.at/english/index.shtml

- http://www.livescience.com/history/ap_060103_mozart_skull.html

- http://www.livescience.com/history/ap_060109_mozart.html

- http://europeanhistory.about.com/od/famouspeople/a/dyk11.htm

- http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/unsolved_mystery_mozarts_skull/

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/01/0109_060109_mozart_skull_2.html

- https://www.academia.edu/215794/Mozarts_skull_identification