About

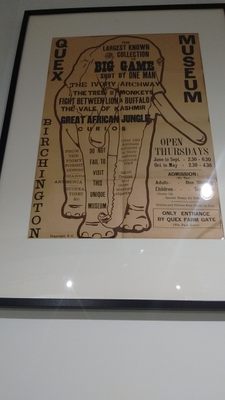

The Powell-Cotton Museum started out as a single room, built on the grounds of explorer and conservationist Percy Powell-Cotton's Birchington-on-Sea estate in 1896 to house the collection of natural history specimens gathered on his trips to India and Tibet. It grew to include more than 16,000 artworks, zoological specimens, and ethnographic objects that he and his family collected on their travels. But it's the dioramas at the museum that are truly notable. These artfully arranged, lifelike displays made Powell-Cotton a pioneer in the field of taxidermy.

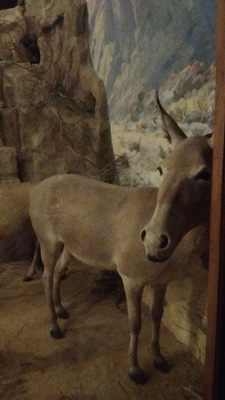

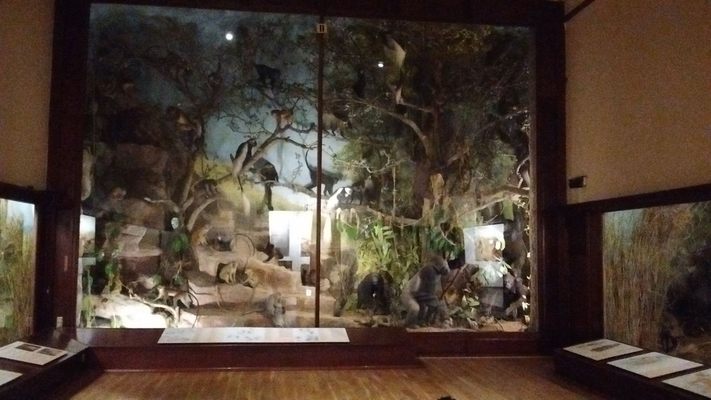

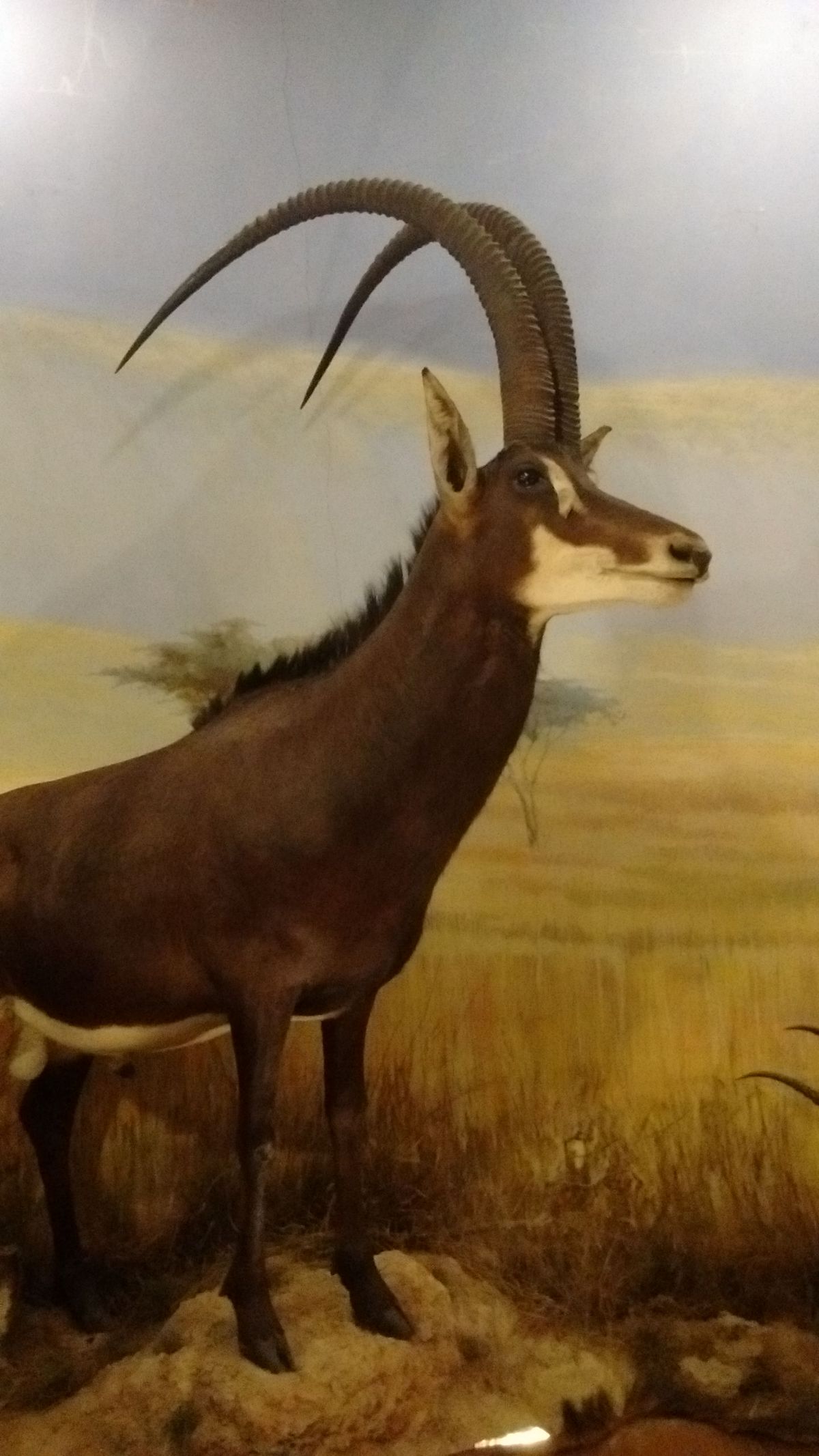

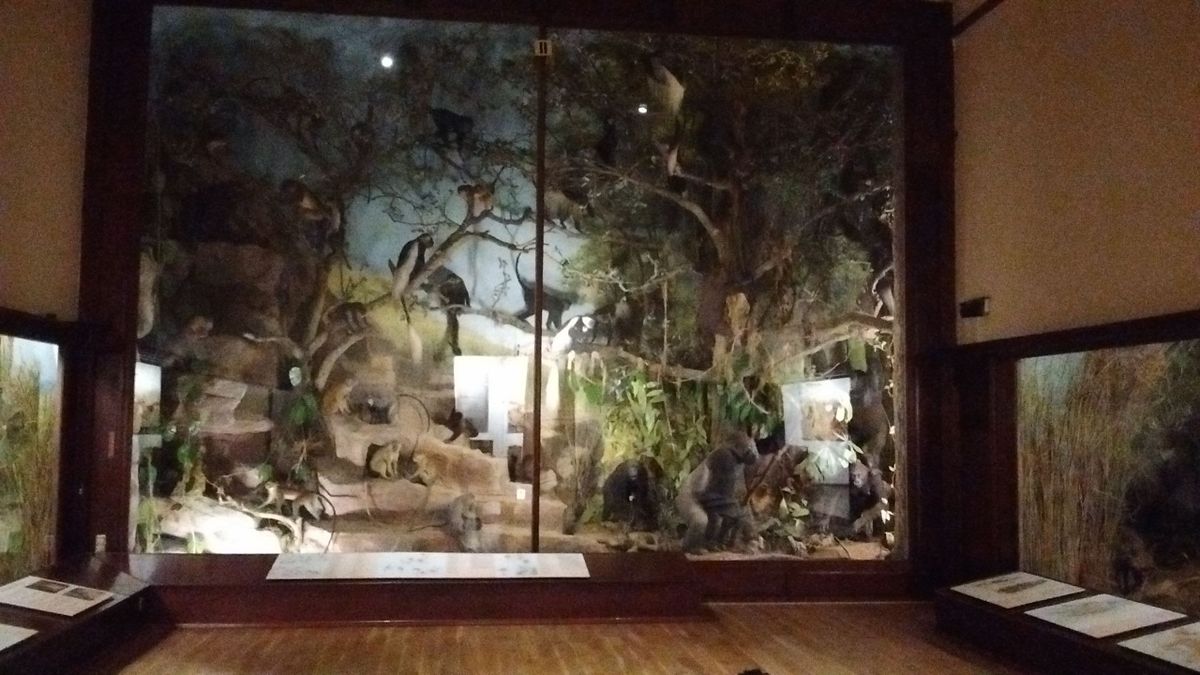

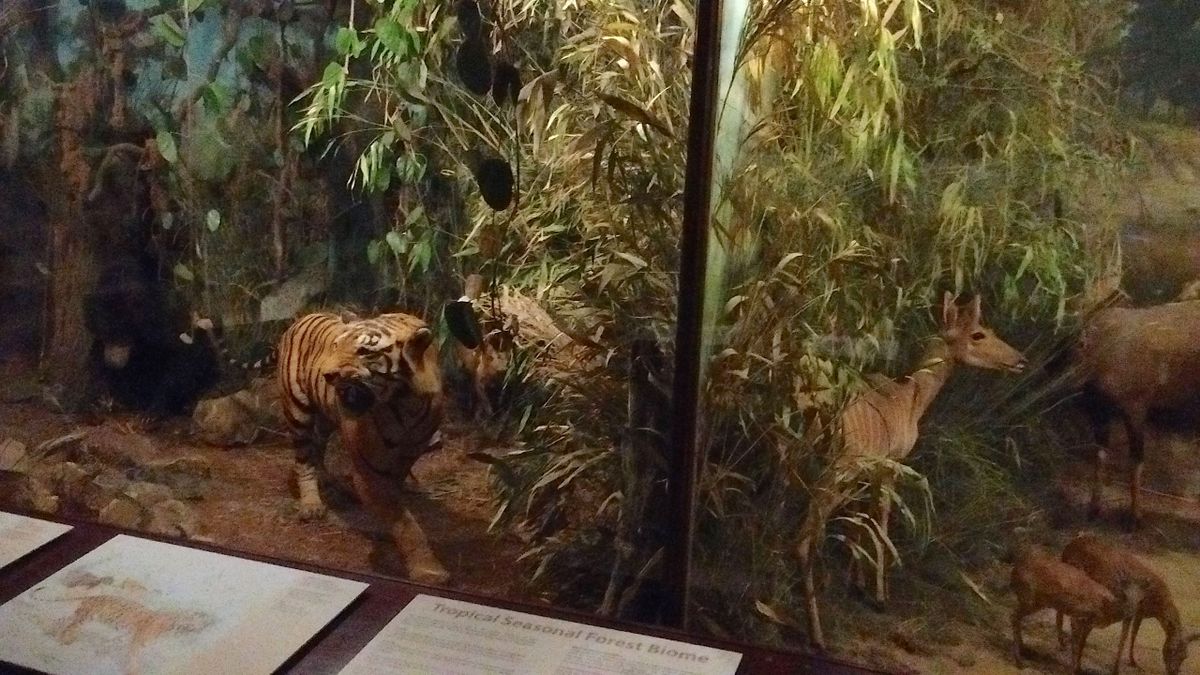

Powell-Cotton created his dioramas to show the animals in surrounding that echoed their natural habitats. At a time when many natural history displays were just mounted animal heads, Powell-Cotton recognized the scientific and educational benefits that exhibiting whole animals could have. He posed the animals in ways to show their facial expressions, body movements, and anatomy. In some instances, the animals' veins and blood vessels are visible.

The painted landscapes in some of the dioramas have impressive and interesting backstories. Many were painted during WWI by a shell shocked Belgian soldier, who was part of a refugee group in exile staying at Quex Park during the war. The soldier, who had become mute due to battle trauma, was a talented landscape painter before the war and was encouraged to craft the backgrounds by Cotton's daughter as a form of art therapy.

Although he was an avid hunter, Powell-Cotton's interests were far more varied than that. He took an interest in helping to catalog many of the animals he came in contact with, taking field notes and photographs. He also took an interest in the people he met along the way, collecting objects and stories that spoke to their lives, experiences, and cultures. Many new species and subspecies were "scientifically discovered" by the major during his trips and a lot of African mammals bear his name. Species "discovered" by the major include the nearly extinct Northern White rhino, (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) a subspecies of honey badger with purely black fur (Mellivora capensis cottoni), a subspecies of the Angolan Colobus monkey (Powell-Cotton's Angolan Colobus), and a subspecies of the African Golden cat (Profelis aurata cottoni) among others.

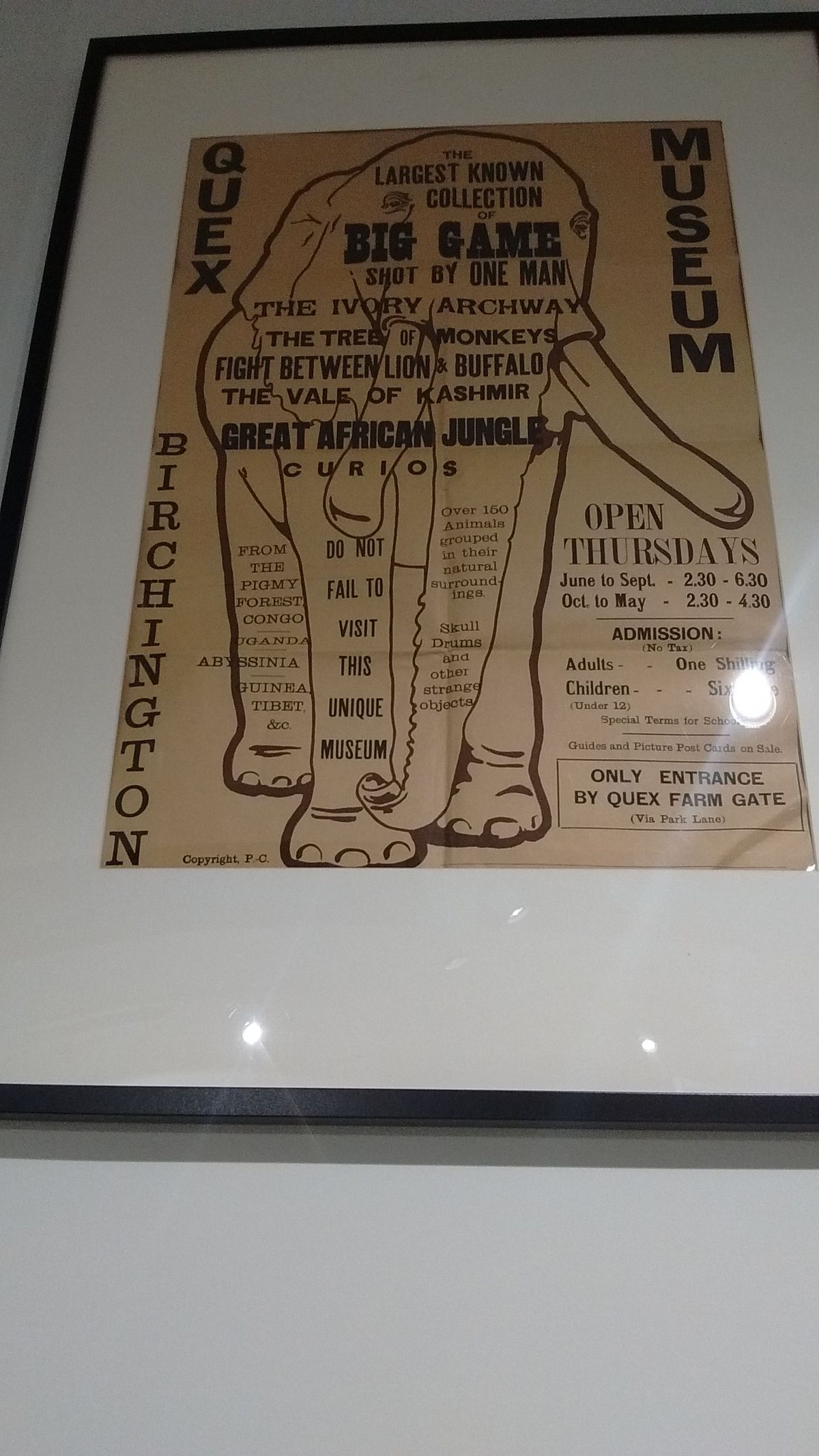

Between the years 1887 and 1939, he traveled throughout Africa and Asia 28 times to collect zoological specimens. In the late 19th and early 20th-century, dioramas were an innovative way to display wildlife, and Powell-Cotton's were certainly no exception. In the days before affordable global travel or nature documentaries, for many poorer Edwardians, visiting the museum on a day trip from a seaside holiday in nearby Margate was a top attraction and the only way that they could experience what the distant jungles of the Congo and mountains of the Himalayas and see what their wildlife might look like.

His collection is now displayed in eight galleries, each representing a different aspect of Powell-Cotton's travels, from Chinese Imperial porcelain to his remarkable dioramas. In Gallery 2, a diorama representing the Himalayas at dawn is considered the oldest untouched diorama of its type in any museum, and to this day remains visually impressive. There are also over 30 films (some of which may be watched on visual displays) Powell-Cotton and his daughters made of their travels to Sudan, Somalia, and Angola.

Many of the specimens within the dioramas have fascinating and eccentric stories behind them. For example, the magnificent lion that is locked in an eternal primeval struggle to the death with a buffalo in gallery three, thanks to the wonders of Victorian taxidermy, is the skin of the same individual lion that had attacked and almost killed the major during his honeymoon trip to Africa in 1906. The wounded animal suddenly charged the major, pinning him to the ground and clawing him before his security was able to shoot it dead. According to his own accounts his life was saved by a rolled up copy of the satirical magazine Punch, which kept the lion’s claws tearing into the flesh of his stomach. In gallery two you can see the mangled magazine and the major's badly mauled hunting outfit. The Buffalo also has an interesting story as well, as the major essentially "discovered" this subspecies of the Cape Buffalo, Bos brachyceros cotton, hence it being named after him.

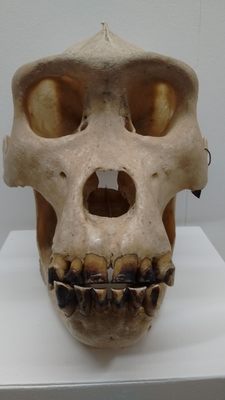

Today, the museum is also active in the field of conservation, working to help protect animals threatened by over-hunting and habitat loss. Artifacts from the museum have helped researchers find solutions for the declining black rhino population through contributing to genetic research and help conserve primates through taxonomic research and to protect habitats.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

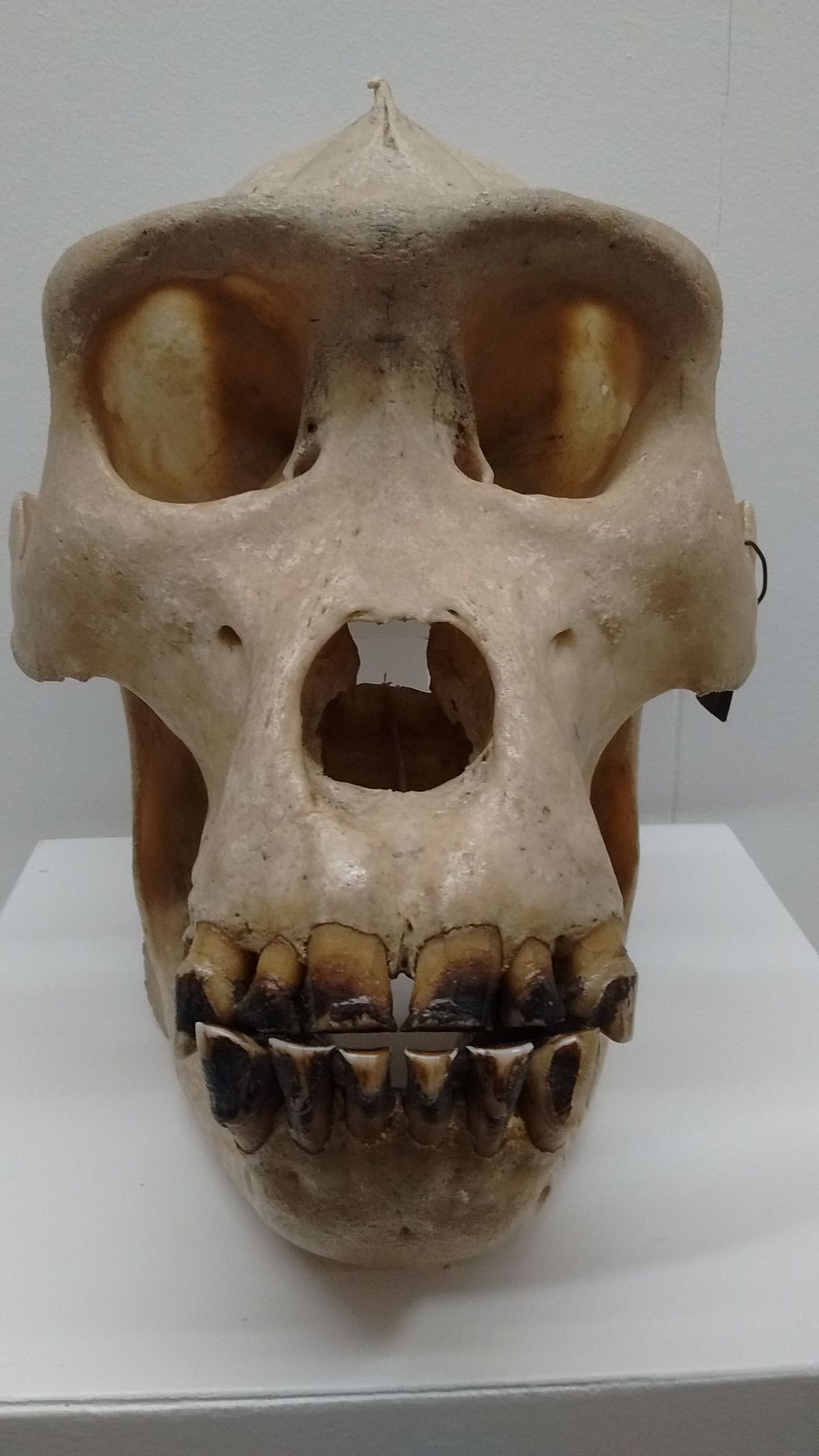

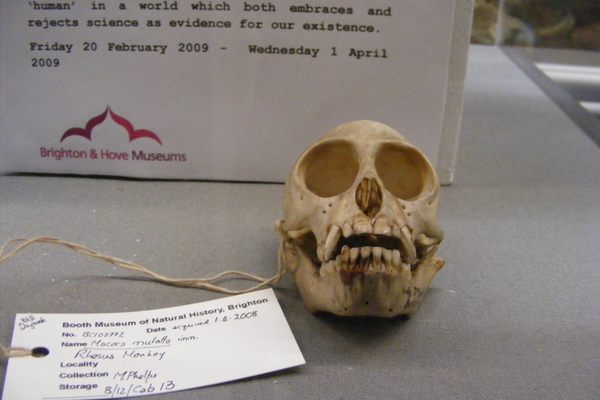

Gallery 6 at the end of the museum is an impressive handling exhibition where visitors are able to handle objects from the museum's collection ranging from tiger and colobus monkey skins, lion or Chimpanzee skulls, Antelope horns, taxidermy crocodile infants, Bronze West African sculptures and Japanese netsukes.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

October 13, 2017