The Untold Stories of the Women Who Led Slave Revolts

Their inspiring acts of resistance were ignored or erased for centuries—until now.

In Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, we talk to female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history.

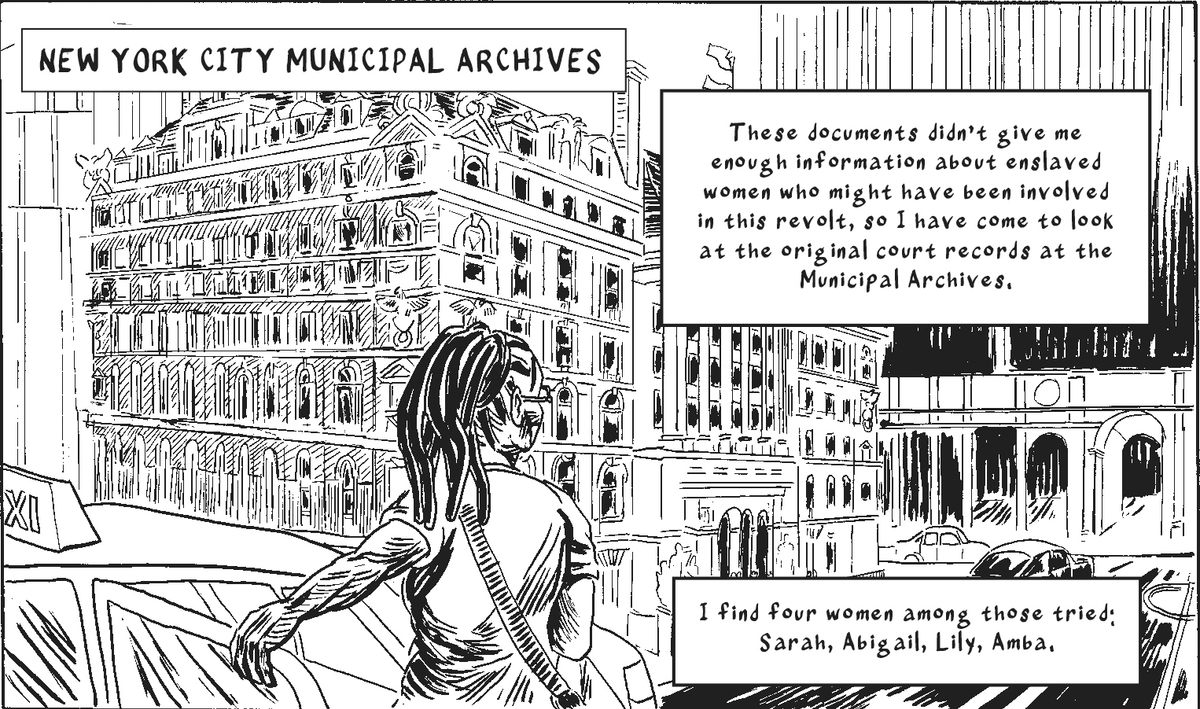

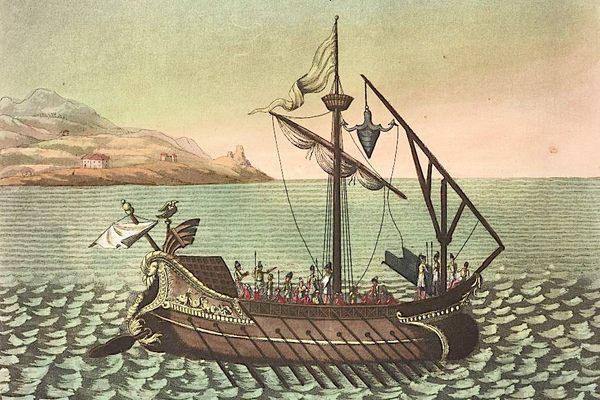

In scrawling cursive, an English enslaver named Robert Norris, captain of the slave ship The Unity, wrote an entry in his log marked June 6, 1770: “The slaves made an Insurrection which was soon quelled…with the loss of two woman slaves.” On June 22, “the slaves attempted another Insurrection after the death of a girl slave.” Then again, four days later on June 26, “a few of the slaves got off their Handcuffs but were detected in Time.” That’s three uprisings on one ship, in less than a month, all involving female African captives. Historian Rebecca Hall, author of the graphic novel Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts, says that’s not an anomaly; enslaved women and female captives led numerous uprisings, such as those onboard The Unity.

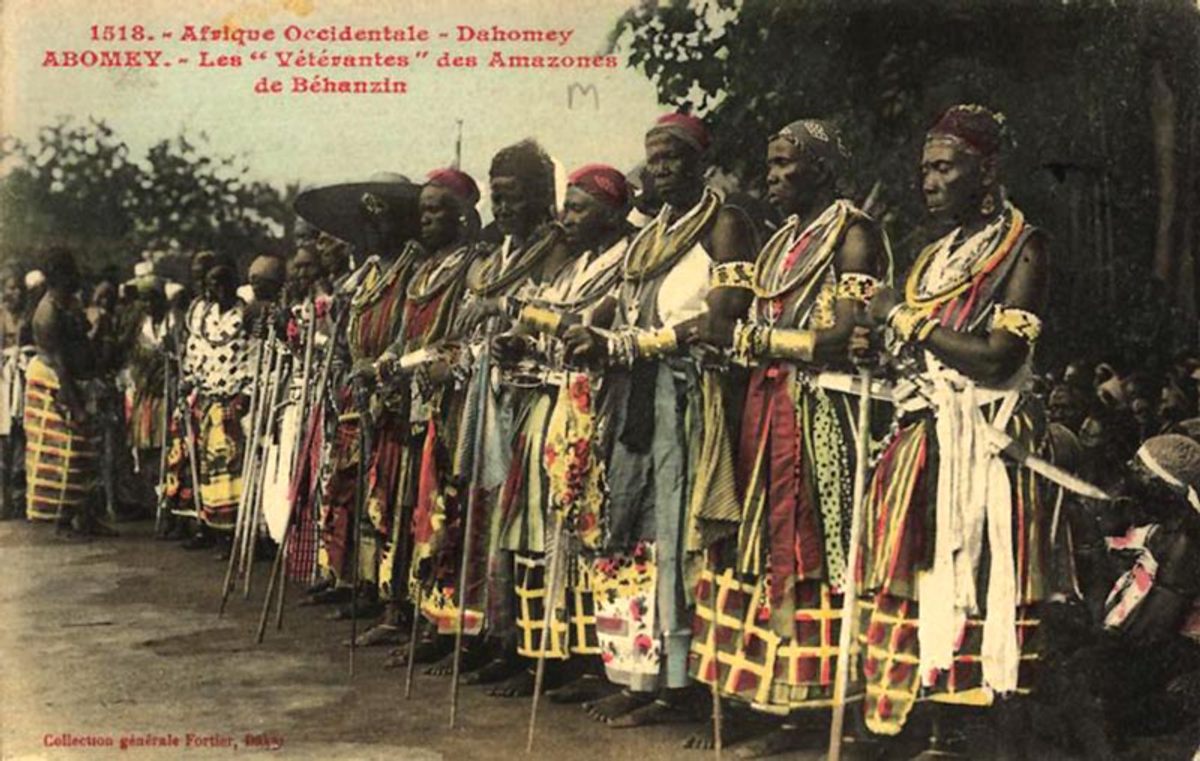

In her new book, Hall opens with a “measured use of historical imagination,” working with her illustrator, Hugo Martínez, to visualize how the women on board The Unity fought back in 1770. It wasn’t hard to do, considering that 227 of the African captives on board were sold to Norris in Abomey, the capital of Dahomey, where women were trained as skilled warriors. “There were constant revolts,” says Hall. Atlas Obscura spoke with Hall about why she’s drawn to these women, such as “the Negro Wench” who led a 1708 slave revolt in New York City, and their enduring legacy.

What is it about female warriors that have drawn you to their stories?

Since I was a little kid, I remember watching women who fought back on TV. I watched Charlie’s Angels and The Bionic Woman. I’ve always been drawn to women warriors because I find the idea of women fighting back in that way very inspiring.

I’m interested in women warriors also as a historical category of analysis. I’m fascinated by the ways in which women warriors are valorized and disavowed at the same time. There are women warriors throughout history, but what happens is that the history is erased or the women become some kind of exception: She became this way because her husband died and she had to take over leadership. It’s always tied to a woman’s role. She ends up becoming the exception that proves the rule over and over again that women aren’t warriors. In my own research in recovering the women who led slave revolts and participated in slave revolts, there was such pushback because people couldn’t even imagine the concept.

What’s the first woman-led slave revolt you uncovered?

A woman led a revolt in what’s now Queens [in New York City]. It was in the city of Newtown, which is [now] Elmhurst. She led a revolt and she was captured. She was burned at the stake and the men who were involved in the revolt were hanged. And I would love to tell you her name, but it’s not preserved. She was referred to as the “Negro Fiend,” so that’s what I call her.

How do we know a woman led this revolt in 1708?

There was one newspaper in the British colonies. It was The Boston Weekly Newsletter. So there are a couple of articles that describe what happened and talk about her. There’s a correspondence between Lord Cornbury, who was then governor of New York [and New Jersey], to the Privy Council in England describing the events. [There was also a 19th-century book, written by a self-styled historian, called The Annals of Newtown.] It describes this revolt and the family that was killed: a man, his wife who was pregnant, and five kids. So those are all the sources related to that incident, and they all refer to this woman—the “Negro Wench” or the “Negro Fiend.”

Your book opens with a female-led revolt on a slave ship. How did you learn about women’s involvement in ship insurrections?

There’s this incredible database. It’s called the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, a searchable database of over 36,000 slave ship voyages. Historians using it found that there was [about one revolt for every ten voyages], which is much higher than anyone expected, because it’s basically suicide. Then they were like, “Okay, so what’s the difference between ships that have revolts and ships that didn’t have revolts?” The only statistical difference was the more women on the ship, the more likely a revolt. And then they just dismissed their own findings by saying, “But we all know that women weren’t involved in this kind of militant fighting.”

What might explain why more women on a ship made a revolt more likely?

[The slave trade] was a highly regulated business. So the rule was when you’re on the coast of West Africa and you’re loading captives onto your ship, everyone was kept below deck and in chains, because there was a risk of what’s called a “cut-off,” where men and women would come and attack the ship and try to free the people on board. So to avoid that, [enslavers] kept everybody chained below deck. But once the ship was in the Atlantic, they took all the women, unchained them, and put them on deck, which is where the weapons were. It was about sexual violence and control, but it was also dismissing women as potential danger sources. A lot of these slavers died because they didn’t take [these women] seriously.

Why are there such detailed records of slave ship insurrections like those on board The Unity in 1770?

The reason why these revolts were documented was for insurance purposes. So Lloyd’s of London or [another insurance company] would insure slave traders and their ships and their so-called cargo. One of the things they would insure them against was something called the insurrection of cargo—which is crazy if you think about it because how can cargo insurrect? So [enslavers] needed to document every revolt, and that’s why there are such good records on it.

What’s the most important thing readers should know about female-led slave revolts?

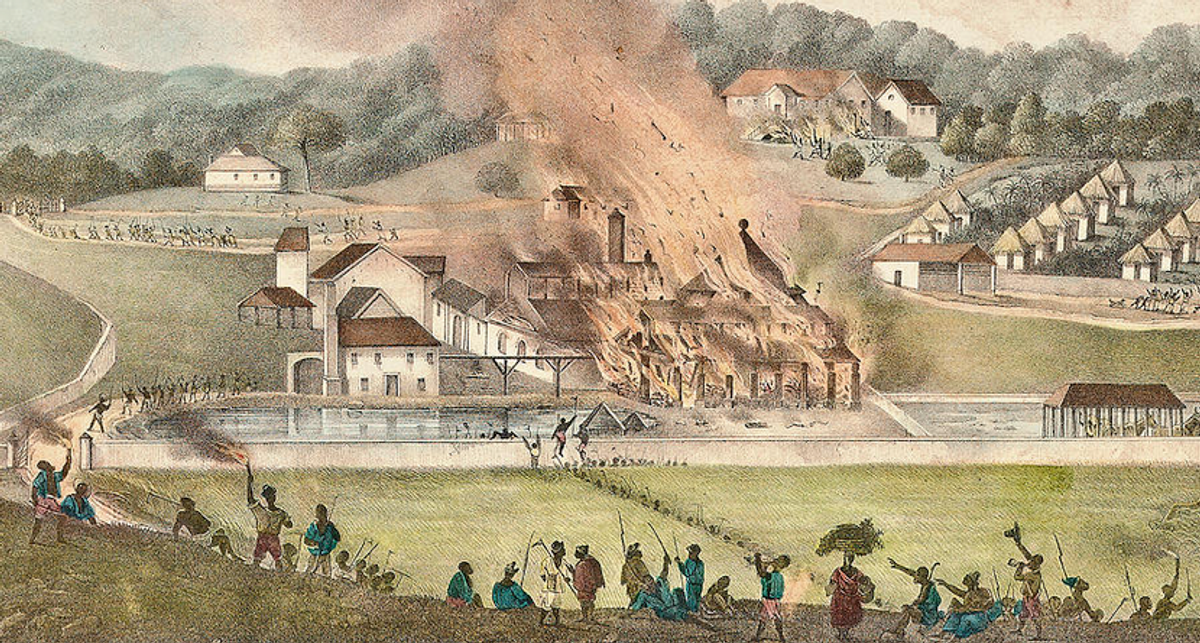

Slave revolts, generally speaking, are so important and underappreciated in the Atlantic world [and] British-American history. So, first of all, I would like people to know that there were slave revolts. There were constant revolts. And that these revolts put so much pressure on—and helped to bring about the end of—the slave trade and the institution of slavery itself. I want people to know that we’ve been fighting this whole time.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook