The Free Cookie in Your Chinese Takeout Is Actually Japanese

Fortune cookies emerged from one of America’s darkest moments.

The streets leading to the vermillion gates of Kyoto’s Fushimi Inari Shrine are filled with mom and pop shops. Vendors sell shaved ice, grilled eels on skewers, lacquered chopsticks, and sweet potatoes baked over red-hot coals. But one man in a crisp white cap is making and selling cookies that don’t look Japanese at all.

Inside his shop, Hougyokudo, Takeshi Matsuhisa presides over a dozen or so round iron molds with long thin handles. Opening one, he peels off a brown disc of dough, then deftly folds it and tucks a slip of paper inside. The finished product is a bit bigger and browner, but otherwise it looks exactly like something most often found atop the check after a meal of spring rolls and chow mein: a fortune cookie.

Fortune cookies—that sweet treat served with a side of pithy wisdom—are such a staple in Chinese-American restaurants that many diners are surprised to learn they are not from China. Often described as an invention of immigrants in California, they can in fact be traced back to Japan, where bakers such as Matsuhisa still make the original version, known as tsujiura senbei or omikuji senbei. “These have been around since the Edo period,” Matsuhisa says.

Fortune-telling culture is strong in Japan. The custom of getting an omikuji, or a fortune printed on a slip of paper at a temple or shrine, stretches back at least a millennium. Worshippers still tie them to sacred trees on the way out. It’s also not uncommon to see palm readers on street corners, and the rokuyo calendar, which predicts lucky and unlucky days, is routinely used when planning weddings and funerals.

Tsujiura is a kind of fortune telling done by interpreting the conversations and characteristics of random people in crowds, especially in sacred places. In the Edo period, this kind of fortune telling became a populist form of entertainment, says Satsuki Matsuhisa of the Matsuya bakery in Kyoto. “In the middle of the Edo period, tsujiura was sold to the common people,” she says. “There were various types of poems written in the 7, 7, 7, 5 [syllable] style, playful poems about love between men and women.” They were sold on street corners and plied by geisha in teahouses.

This ancestry is still apparent in Kyoto’s shops. One fortune from Hougyokudo is a 7, 7, 7, 5 style poem that roughly translates to: “Until becoming a mother / Is not being a mother / Because of an argument at Izumo?” Since Izumo is a part of Japan where gods are said to reside, the implication is that having a child is up to the gods.

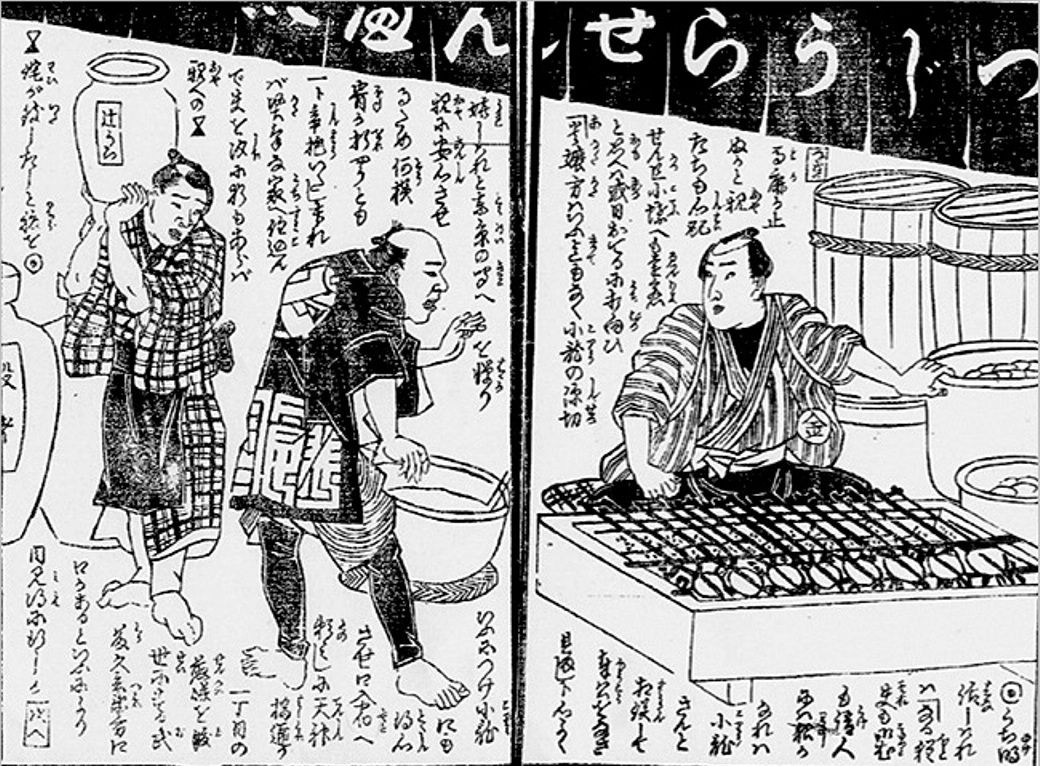

References to Japan’s fortune cookies go back centuries. One of the earliest is a passage in Tamenaga Shunsui’s “The Young Grass of Spring,” which describes brittle cookies containing fortunes. A woodblock print from 1878 depicts a character named Kinnosuke making tsujiura senbei in an Osaka shop using the same method followed by bakers in Kyoto today. And the zoologist Edward Morse memorialized them with a sketch in his 1883 book, Japan Day by Day Vol. II. He writes that the cookie was “pinched up in a triangular form” and “was made of molasses and was brittle, and tasted like a gingersnap without the ginger.” The message inside the cookie, Morse wrote, was a motto: “Determination will go through rocks, why then can we not be united?”

When the fortune cookie appeared across the Pacific, in the United States, it did so in California, the home of fast-growing Chinese-American and Japanese-American populations.* Immigrants from China began arriving in large numbers in the 1800s, drawn by the Gold Rush and the need for agricultural, factory, and railroad laborers. Japanese immigrants came soon after, in later decades.

White Americans described their growing presence as a “yellow peril” and passed xenophobic laws in response. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 halted all immigration from China. When industrialists recruited Japanese workers to fill the gap, similar laws soon blocked their arrival, including, eventually, the 1924 Immigration Act that prevented all new immigrants from Asia.

As the Gold Rush waned, those in cities were shunted into low-wage jobs such as restaurant and laundry work, often congregating in enclaves due to policies limiting where they could live. It was in these enclaves that several people—of both Chinese and Japanese ancestry—claimed to have originated the American fortune cookie. But the best and earliest evidence points to San Francisco’s Japanese Tea Garden.

Established in 1894 by Makoto Hagiwara, who came to the U.S. in the 1870s and started several businesses, the Japanese Tea Garden still serves fortune cookies in Golden Gate Park. “There’s been several references to the Hagiwara [Japanese] Tea Garden ‘tea cakes,’” says Rosalyn Tonai, executive director of the National Japanese-American Historical Society, in reference to the earliest accounts of American fortune cookies. Served with tea, the cakes contained thank-you notes, which, Tonai says, “evolved into the fortune cookie we know today.”

“The idea of writing something inside began with a party Hagiwara held for his vendors and other guests,” says Benh Nakajo, who has worked at the Japanese Tea Garden for 10 years and for nearly 50 at Benkyo-do, a confectionary in San Francisco’s Japantown that was founded in 1906. After the cookies were popular with visitors, he adds, Hagiwara replaced the thank-you note with a fortune.

The Hagiwaras introduced the cookie between 1910 and 1914, and outsourced it to Benkyo-do in 1918, when they could no longer handle the volume, writes Gary Ono, the grandson of Benkyo-do’s founder, Suyeichi Okamura. The cookie had a savory flavor from miso or soy that wasn’t as popular in America, so Okamura suggested they sweeten and lighten it by adding vanilla flavor.

As the cookies gained popularity, more Japanese bakeries in San Francisco and Los Angeles began making them. In addition to selling them to the public, the bakeries also supplied them to Chinese restaurants, many of which were owned by Japanese people, as Japanese food wouldn’t become popular for at least 50 years.

Pearl Harbor accelerated the fortune cookie’s cross-culture journey. When the United States entered World War II, the government rounded up Japanese Americans across the West Coast and interned them in camps. Their businesses and homes were shuttered, including Japanese-owned Chinese restaurants and most of the bakeries that made fortune cookies. Both the Hagiwaras and the Okamuras were imprisoned. The Japanese Tea Garden was renamed The Oriental Tea Garden, the Hagiwaras were replaced by Chinese staff, and the Hagiwara home and the Garden’s Shinto shrine were destroyed. Benkyo-do closed as well.

In the vacuum, Chinese businesses thrived. “San Francisco’s Chinatown quadrupled its businesses between 1941 and 1943,” writes Jennifer 8. Lee in her book The Fortune Cookie Chronicles. “A sharp rise in the demand at Chinese restaurants combined with a lack of Japanese bakers gave Chinese entrepreneurs an opportunity to step in. One of America’s beloved confections emerged from one of the nation’s darkest moments.”

Chinese restaurant by Chinese restaurant, fortune cookies spread from San Francisco and Los Angeles across the country. Eventually, they became vastly more popular and well known than their Japanese ancestors, and so associated with American-Chinese food that Gary Ono had to rediscover the role his family, and Benkyo-do, played in bringing fortune cookies to America.

Today, you can still find fortune cookies being made traditionally in a few places in Japan. In the precinct around Kyoto’s Fushimi Inari Shrine, a handful of family-run shop owners are emphatic that tsujiura senbei are homegrown. “This kind of senbei has existed since the end of the Edo period,” says Masakiyo Go of Souhonke Inariya, whose grandfather founded the shop because he liked the area’s cheerful mood and spiritual atmosphere.

Along with nearby Hougyokudo and Matsuya, Souhonke Inariya’s’s cookies, says Go, are modeled on miso senbei from Ogaki City, which is about 70 miles away. There, a company called Tanakaya Senbei, whose process and product look just like the ones at Fushimi Inari, has been making cookies for 160 years. The one key difference is that Tanakaya Senbei’s cookies are flat, lacking the distinctive suzu, or “bell,” shape.

At Matsuya, you can watch the baker pour batter made from flour, sugar, miso, water, and sesame onto a hot iron-grill mold called a kata. Ten minutes later, as the batter starts to brown, the baker peels it from the mold and folds it in half, then again, tucking in a fortune while it’s still warm. Working a dozen or more kata at a time, he’ll rotate them as they bake. “They get shiny, which is different from regular rice crackers,” says shop proprietor Satsuki Matsuhisa. “They become glossy, which takes special technique and is not easy to do. I’m proud of these.”

To anyone familiar with American fortune cookies, the end result is both instantly familiar and clearly distinct. The brown, crispy cookies are nearly double the size of the typical American specimen. They’re thicker, too, more hearty and less sweet than their counterparts. The miso adds an underlying note of savory tang, and the sesame lends a nuttiness. The fortunes themselves are reminiscent of a shrine’s omikuji: great luck, middle luck, small luck, and future luck, accompanied by a cryptic line or two.

Japanese bakers are well aware of the fame of American fortune cookies. “Hagiwara is not the one that made the cookies originally,” says Go. “He just brought the technology from Japan.” Still, English-language articles mentioning Souhonke Inariya and Benkyo-do hang on the walls. Gary Ono, who visited in 2017, says he was struck by their similarities. At this point, both families have been making a version of these cookies for several generations.

For his part, Takeshi Matsuhisa reckons that sales of tsujiura senbei—to both foreign and domestic tourists—has picked up since people started to realize that fortune cookies originated in Japan.

Fortune cookies may have traveled from Japan to the United States, but you won’t find them on restaurant tables in Japan. Instead, people travel to these specialty shops and take them home to enjoy with tea or coffee. They might be harder to find, but the reward is even sweeter.

*Correction: This post previously described fortune cookies appearing “across the Atlantic, in the United States.” It has been corrected to say that the United States is across the Pacific from Japan.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook