The Unsettling Legend of Maryland’s Native Cryptid, the Snallygaster

A strange, scary farce that brought together Old World legends and racist scare tactics.

On an unrelentingly hot day in August, I drove out to the borderlands between Maryland and Pennsylvania to see a museum that does not yet exist, devoted to a creature that never has. Sarah Cooper’s day job is as a travel ER nurse, but in her spare time she travels to various festivals and conventions with her collection, what she calls the American Snallygaster Museum—her goal being to open up a permanent site devoted to Western Maryland’s strange cryptid.

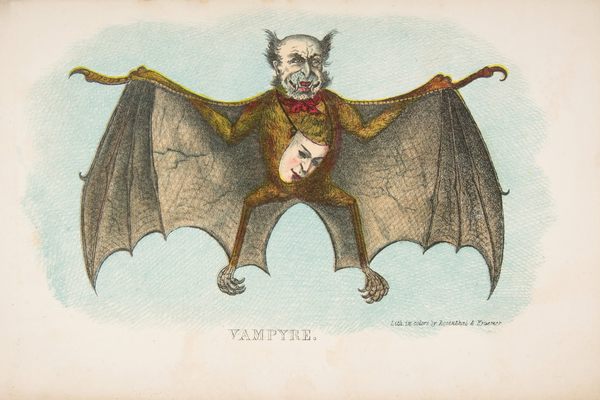

The Snallygaster is difficult to define—a baffling mixture of body parts and features that seems to change based on who’s telling the story. When its existence was first reported in 1909, in the Valley Register, a newspaper published out of Maryland’s Frederick County, it was described as having “enormous wings, a long pointed bill, claws like steel hooks, and an eye in the center of its forehead.” In the century since, descriptions have varied, tending toward the elaborate: T. S. Mart and Mel Cabre’s A Guide to Sky Monsters lists it as “Half reptile, half bird” with a “tentacle-like tongue and sharp teeth,” and Ed Okonowicz’s 2012 Monsters of Maryland: Mysterious Creatures in the Old Line State describes it as having “sharp talons made of hot glowing metal” and “possessing several octopus-like tentacles.”

When I arrived, Cooper took me into her kitchen, where she’d set out a selection of her museum’s holdings: newspaper clippings, several children’s books (including Fred Flintstone and the Snallygaster Show), and a model of the creature perched on a log, with black wings, silver claws, one eye, and a face full of red tentacles. Interpretations of it seem to tend toward the ineffable, the Lovecraftian: less garden-variety cryptid than otherworldly demon. Cooper first heard about the Snallygaster when she moved to the area in 2013 and was intrigued by the extensive local coverage and knowledge of something she’d never heard of before. Though she’s never put any stock in the creature’s actual existence, she’s made it her mission to give it a bigger presence, partly to attract tourists to the place that’s now her home, and partly to offer insights into the region’s odd and sometimes upsetting history.

Unlike some other cryptids, the Snallygaster’s origins are easy enough to trace. In early 1909, some strange tracks left in the snow outside a New Jersey home led to a furor over the “Jersey Devil,” now a beloved member in the pantheon of American cryptids. The story quickly gained national traction and Maryland-based journalists, it seems, wanted in on the action. Less than a month after the Jersey Devil sightings began, the Valley Register ran a story about a man named Bill Gifferson who had been walking home when a winged creature attacked him, carried him up to a hill, slashed his jugular with its beak, drained his blood, and finally dumped his lifeless body in a ravine. A flurry of other stories and sightings followed, including one report of a man who happened upon the Snallygaster as it was draining a hundred-gallon tub of water, after which it exclaimed, “My, I’m dry, I haven’t had a good drink since I was killed in the Battle of Chickamauga,” as though the fearsome, dragonesque creature was somehow the ghost of a dead Civil War soldier. This went on until July, when a final dispatch from the Valley Register described a scientific expedition to discover the nocturnal monster’s lair, whereupon it erupted from the ground and flew off to Virginia.

The excitement got as far as Baltimore, but the Snallygaster failed to enter national lore as the Jersey Devil had. But just because something is so obvious a hoax doesn’t mean it doesn’t have something to tell us. The Snallygaster, copycat that it is, offers a strange, fascinating, and upsetting story of its own. It’s a story about what hides in the mountains, stalks the woods, and lurks in the shadows, about real forces that get associated with the strange and impossible.

The name appears to have derived from the German schnelle geist, or “quick ghost,” a term that usually denotes some kind of poltergeist. In the 19th century, Western Maryland saw a flood of German immigrants, who settled there as the Seneca people were pushed farther west. They brought their folklore and superstitions—both ghosts and the belief that mountains were inhabited by dragons. As the physician and polymath Johann Jakob Scheucher had written in his 1723 travelogue of the Alps, the mountains were filled with “scaly dragons and slimy dragons, dragons with wings and feet, dragons with two legs and four legs, with and without wings, and sometimes without wings or legs, but with objectional heads with semi-human features, and an expression at once humorous and malignant.” These beliefs found their way to the Appalachians. Madeleine Vinton Dahlgren, a D.C. socialite who relocated to Maryland in the 1870s, published a book of local folklore, South Mountain Magic: Tales of Old Maryland, in 1882. It included the tale of the “Hoop Snake,” a dreaded creature that “puts its tail in its mouth, when in pursuit of its victim, and rolls on with an incredible rapidity. The reptile wears a horn on its head, and kills whatever it touches!”

Decades later, the Jewish-Austrian literature scholar Leo Spitzer (who’d escaped his home country in the 1930s and settled at Maryland’s Johns Hopkins University) suggested that the Snallygaster was likely instead derived from “The Wild Hunt,” an old story with Norse and Christian origins. In it, a troop of damned souls ride the sky between Christmas and the Epiphany, chased by the Wild Hunter (the Norse god of wind and the dead, Odin), snatching unwary travelers (especially children) along the way. Aside from Spitzer, very few scholars have attempted to unravel the meaning of the Snallygaster—it is perhaps too obscure, too regionally focused, or just too bizarre.

The Snallygaster seems to have emerged from the Old World, but by the time it found its way into print in the United States, it taken a far more fantastical and bizarre aspect, with reports of it sounding more like absurd tall tales than either journalism or traditional folklore. During the initial flurry of reports, the Hagerstown Mail ran a report that the Smithsonian had attempted to classify the creature: “They write back that it is either a winged bovulopus or a Snallygaster, as it has some of the characteristics of both. These animals are exceedingly rare and the hide of the Snallygaster is said to be worth a hundred thousand dollars a square foot as it is the only thing known that will properly polish punkle shells used by Africans of Umbopeland for ornaments.” This litany of nonsense with a vaguely scientific veneer, is what P. T. Barnum would have called a “humbug”—not so much a hoax, per se, but what Barnum self-servingly described as a put-on by an “honest man” who nonetheless “arrests public attention.” The humbug invites you in on the gag, daring you to both believe or disprove its wild claims. As Kevin Young explains in his book Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Faces, and Fake News, the humbug works by “making the audience part of the hoax, saying effectively, you’re smart, or better yet, you think you’re so smart: come and see for yourself.” Barnum’s success was in his boasting about obvious forgeries. So, too, it was with the Snallygaster—an obvious farce delivered with a straight face.

Sarah Cooper’s ultimate hope is to play with this very idea in a museum format—modeling the structures of a traditional natural history museum for a creature that seems to deliberately defy any stable, taxonomical possibility. She imagines displays and specimens and discussions of its classification that all play up how strange and amorphous the thing itself is. For now, it’s become a particularly malleable bit of local folklore, a name for anything weird that goes bump in the night. Cooper says that people from the region have told her about growing up with its presence. One told her, “My grandpa would tell me how it would hide in the port-a-potties and bite you on the butt.”

Because it lacks any clear definition, the Snallygaster is well suited to adapt with the times. In 1932, new reports appeared suggesting that the cryptid was drawn to moonshine stills hidden in the mountains. On December 12, the Register announced that the Snallygaster had fallen into 2,500-gallon vat of backwoods liquor after being overcome by the fumes. By the time officials got there, the alcohol had completely eaten away at the animal, leaving only its bones, which were, for some reason, subsequently dynamited. (Dragon Distillery in Frederick now sells its own “Snallygaster Rye.”)

The Snallygaster seems to have been invoked by Marylanders whenever something suspicious was in the news, often with a wink. When a UFO (what we might call a UAP today) was sighted in July 1947, the Frederick News scoffed that flying saucers “cause little reaction in Middletown Valley. Middletowners have had snallygasters to talk about since 1909.” In 1949, after Maryland passed the Subversive Persons Act (spearheaded by lawyer Frank Ober), which required candidates for public office to take a loyalty oath, the Baltimore Sun reported that the Snallygaster had been seen in Massachusetts, where it was “quoted as saying it was trying to escape the Ober bill.” Through the years this monstrous mountain dragon has become associated with various invisible elements of culture, as though a thing could only become really real once this unreal creature had formed an opinion. And what emerges in all these old reports is that the Snallygaster—an invisible thing, perpetually hidden—was most often invoked in connection to other invisible, unseeable things. Bootleggers, flying saucers, communists—anything out of the public eye (intentionally or due to nonexistence), anything feared or wondered about—Marylanders connected these things in particular to the Snallygaster.

Beneath these seeming frivolities lurks something darker, stranger. Many of the original reports of the cryptid strikingly note that the Snallygaster specifically preyed on Black people. On February 12, 1909, the same day that the NAACP was founded, the Valley Register ran a story titled “The Colored People Are in Great Danger,” which described the creature and how “this vampire-devil only attacks colored people.… It is seldom seen during the day, feeding at night only, and the strange part is that it seems to prefer colored men to colored women, though it attacks the latter at times.” Another article from that period quotes an eyewitness who claimed that the Snallygaster “was an omen of ill for colored voters who deserted the Republican party in the Presidential election.” For all its apparent silliness, there was a not-at-all-hidden threat baked into the legend.

As a border state that permitted slavery but never joined the Confederacy, Maryland has a fraught racial legacy. After Emancipation, the Black community in Western Maryland was initially left to fend for itself as white enslavers refused to pay for work they had previously gotten for free. Organizations such as the Freedmen’s Bureau quickly stepped in to provide housing, places of worship, and jobs, and in a short time some newly emancipated Marylanders there seemed like they might have a chance to thrive. An 1870 census taker told a local newspaper at the time that the Black families of Western Maryland all “seemed to be industrious, well-to-do, and intelligent.” However, by the turn of the century, Black Marylanders were leaving for Baltimore and other urban environments—and this context that offers a full appreciation of the Snallygaster’s origins.

Reports, for example, that the “great bird preys upon Negro children out after dark,” are in keeping with the kind of weaponized superstition tactics that were common in the South, before and after the Civil War. Folklorist Gladys-Marie Fry’s 1975 Night Riders in Black Folk History documents the numerous ways in which whites would attempt to use urban legend, folklore, and the supernatural as means of control. “The primary aim of such pressure was to discourage the unauthorized movement of Blacks,” she writes, “especially at night, by making them afraid of encountering supernatural beings…. From the post–Civil War period to World War I, the method helped to stem the tide of Black movement from rural farming communities in the South to the urban industrial centers of the North.” As one of her sources, Evelyn McKinney, explained in 1964, “These stories were about things that happened at night. And these were the things that kept you from going out.… I mean these things that kept you in fear not of the master himself, but of the supernatural. You knew that you may be able to avoid the master because perhaps he was sleeping. But you couldn’t avoid the supernatural.”

There were ghosts that haunted crossroads, forests, and cemeteries (all of which, particularly before Emancipation, would have been vital thoroughfares for those escaping slavery). There were “Night Doctors,” men who lurked in Northern cities and kidnapped and murdered Black people for use in anatomical dissection and medical experimentation. It was not uncommon, particularly during the first era of Ku Klux Klan activity during Reconstruction, for a group of white men to show up on the porch of a Black sharecropper after midnight, claiming to be the ghosts of Confederate soldiers. (Suddenly the “Chickamauga” Snallygaster story becomes clear.) It was a violent and malicious kind of humbug: an “honest” hoax, so to speak, that dared its victims to disbelieve.

Fry also documents how supernatural beasts served similar purposes, as “marauding night creatures. Generally the animal to be feared was not named but only partially described, which added to the slave’s fear by leaving his imagination free to explore all kinds of terrible possibilities.” Headless animals were also popular. As another source related to Fry, “They would have a puddle of blood and claim that something came and killed someone…. Well, they would make as though there was probably some ferocious animal, or some spirit coming back. I mean, they used all types of tactics to keep people afraid down there.”

The Snallygaster—ambiguously described, operating at night, preying on Black people who stay out too late—belongs to this violent, racist tradition. During the 1932 resurgence of the lore, one local paper even went so far as to connect the Snallygaster to another urban legend, “Uncle Perry.” According to a story well known among older locals, a janitor at the University of Maryland’s medical department was told that he would be paid $15 for bodies that could be used in the anatomy lab. As the legend went, the greedy Uncle Perry began a career of murder and body-snatching. “While the story persisted,” Frederick’s paper The News continued, “none but a boldly venturesome person dared to risk his body out of the house after sundown…. During the time this story prevailed it is said that the streets of Frederick were clear of hundreds who usually were seen going back and forth.” The Uncle Perry tradition, the paper concluded, is still well known, and “has the earmarks of the ‘snallygaster’ tale.”

Sarah Cooper doesn’t shy away from this, and wants this part of the Snallygaster story told as well. “A big thing for me,” she says, “was watching memes like Peppy the Frog get turned into racist dog whistles.” She fears a story like the Snallygaster could “easily become that.” Thus she wants it a prominent part of her future museum. “I feel like part of making the museum and part of acknowledging the ugly history,” she says, is that it “prevents people from making it into a racist dog whistle…. I don’t ever want it to become something ugly again. I want it to be something interesting and something we can learn from.”

The Snallygaster was born of an unholy union of Germanic legends and racist scare tactics, the Wild Hunt and Night Doctors, Odin and the Klan. But thankfully, its story did not end there. Its history reflects the durability of American folklore, for both good and ill. The Snallygaster’s lack of any kind of definite form may be what has allowed it to persist, adapt, and teach. Maybe some day soon it will fly again over Western Maryland—with a whole new shape.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook