An Elegy for Colombia’s Tropical Glaciers

“We are the place on Earth where glaciers shouldn’t be, and they are here.”

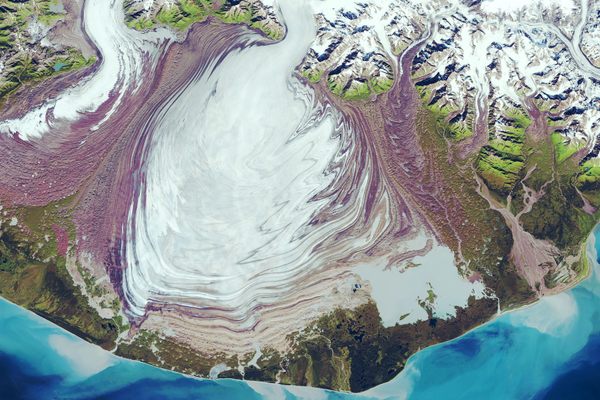

As Jorge Luis Ceballos scales the steep mountain slope, the memories of the past 15 years wash over him. His shoes crunch on frigid gray rock. Only a few years before, it was covered in the ice of Nevado Santa Isabel, one of Colombia’s few remaining “tropical glaciers.” But he’s watched it disappear before his eyes, leaving behind only dates, spray-painted in red on nearby rocks—1960, 1970, 2003, 2006, 2013, 2017—each farther up the mountain than the one before. According to the latest research, in 30 years or less, all that will be left of Colombia’s glaciers will be those numbers.

“This is a glacier that is perishing,” Ceballos, 56, says, his backpack full of heavy scientific gear. The thin scientist comes across a lingering patch of wet, crackling ice and lets his hiking pole sink into it. “It’s dying.”

The very existence of tropical glaciers—rivers of ice near the equator—seems to defy logic: flukes of weather, nature, and topography. These formations survive in the tropics because of both elevation, high in the mountains, and connections with lower ecosystems—in this case Andean forest and alpine grassland called páramo that keep them fed with precipitation.

Only three zones of the world have such glaciers: the Andes (Peru has the most tropical glaciers by far), scattered mountains in East Africa, and parts of island Southeast Asia. Existing in such a precarious balance, it’s little surprise that these ice islands in the sky are disappearing rapidly.

“They are truly at the front line of climate change,” says French glaciologist and science television host Heidi Sevestre. “These are not glaciers that are going to disappear in 100, 200 years, these are glaciers that are going to disappear in the next few years.”

As a whole, Colombia has already lost 90 percent of its ice, according to a report by Colombia’s Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology, and Environmental Studies (IDEAM).

Ceballos has tracked these melts since 2005, the first year the government began to collect comprehensive data on them. Now Ceballos travels through Colombia’s coffee region and up into the sky once a month to reach the most “terminally ill” of the six, Nevado Santa Isabel.

The glaciologist—sometimes with a team, sometimes alone—winds along a rocky road in a 4x4, first through dense jungle that fades into highland meadows, where he hikes for hours among espeletia plants, sunflower relatives also known as “frailejones” or “big monks.” With mules led by a local farmer lugging scientific equipment, Ceballos arrives at the ice cap, which sits wedged, almost hidden, in a crook of the mountain. Few Colombians even know the country has glaciers amidst its snow-covered peaks.

Among the six glaciers in the country, and one more in Venezuela, El Cocuy is the strongest, Ceballos says. It winds between 21 robust snow peaks up against the Venezuela border. The Sierra Nevada lies in indigenous lands near the northern coastal city of Santa Marta, hovering over dense jungle and largely inaccessible even to the scientists attempting to study it. In neighboring Venezuela, Humboldt is even more deteriorated than even Santa Isabel, and is letting out its last gasp.

“As a scientist you’re not supposed to talk about emotions, you’re not supposed to talk about the way you feel,” says Sevestre. “But you couldn’t help but feel so sorry for these glaciers.”

For years Ceballos’ work has involved drawing lines—literally—as he spray-paints rocks to mark the level of the ice, and then returns to see how much farther the ice has retreated. He soon connected with researchers in Peru and Argentina—which have many more glaciers than Colombia—and increased the detail of his studies by drilling holes in the ice to document the melt with long orange poles.

“It was the first data, you could know how a glacier here in Colombia behaved,” he explains. “How it grows, and shrinks, grows, shrinks. We began to see that it was shrinking more than it was growing.”

Surrounded by low-hanging clouds, Ceballos and his assistant Andres Cruz Mendoza check the poles sticking out of the ice, take measurements and photographs, and then scrawl the bleak results into a notebook.

In just a month, the glacier had lost, staggeringly, nearly nine feet of depth. Ceballos says his hope has gone with it.

“The damage has already been done,” he says. It’s almost as if he’s playing historian when he visits nearby schools to explain his work. “Now I’m turning into a storyteller about what happened.”

Young activist Marcela Fernández has the same impulse, but where Ceballos saw an elegy, she saw a call to action.

The Colombian was surprised to learn—just a year ago—that the glaciers even existed, when she read a story about their decline in a Colombian newspaper. They were “disappearing in silence,” she says, so she formed Cumbres Blancas, a coalition of glaciologists, including Ceballos and Sevestre, photographers, mountaineers, and activists dedicated to at least documenting the glaciers.

“We have to say goodbye properly. If they are going to disappear, they are not just going to go away and vanish all of the sudden,” she says. “They need company, we need pictures, we need to document. You don’t let a terminally ill person die alone. That’s what’s happening with our glaciers.”

Sevestre is particularly concerned about what the loss of the glaciers will mean for local populations who rely on them as sources of water. For Fernández, the rapid melts are also a sign of pieces of indigenous and Colombian culture withering away.

Deep in the Santa Marta mountains, near the Sierra Nevada glacier, the Kogi indigenous people believe that humankind’s purpose is to maintain the nature around them. The culture worships the interconnected ecosystems represented by their glacier—the cycle of water, snow, and ice that also feeds the páramo and the dense jungles below. Their traditional dress includes white, bell-shaped hats to represent the snow peaks.

“They know everything is interconnected and that the drop of water that comes from up there, Fernández says, “it’s the one that feeds the crop, it’s the one that makes snow clouds.”

Scientists believe these glaciers are past saving, but Fernández says Cumbres Blancas hopes to use their example to spur action to save other tropical glaciers around the world.

In recent months they’ve worked on a documentary to pressure Colombia’s government to allocate more funds to preserving the glaciers and showing the public that they exist. If nothing else, they want Santa Isabel to stand as a warning.

“We want to make Colombia the place where this glacier revolution starts,” she says.

“We are not Antarctica, but we don’t have to be Antarctica. We are the place on Earth where glaciers shouldn’t be, and they are here,” she adds. “We still have hope, and we still have snow.”

As Ceballos treks along Santa Isabel, he peers up at the cracks zig-zagging up the ice face, streaked with ash from the nearby volcano. They seem to mirror his mood.

“It makes me feel …” he says, trailing off.

“Nostalgia?” asks Mendoza.

“No,” he answers, “something more feo, ugly.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook