This Seattle Arts Building Was Once an Immigrant Detention Center

Inscape Arts takes its name from the Immigration and Naturalization Service, or INS.

When Jayashree Krishnan was 21 years old, she walked through the doors of an imposing government building in Seattle’s Chinatown, hoping to become a citizen of the United States. The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) building had bars on its windows; it determined the fates of countless people, issuing green cards and passports while also detaining and deporting thousands. “The first time I was here, it felt very impersonal and cold,” Krishnan says.

The building now stands transformed. What was once a hybrid government office and immigration jail—and before that, a gold-weighing and assay station dating back to the Gold Rush—is known as the Inscape Arts and Cultural Center. When the INS building closed in 2004, the Department of Homeland Security moved detainees to a privately run detention center. A few years after the move, the city sponsored a loan to purchase and develop Inscape, and today the hulking structure is filled with artist studios.

Krishnan, who originally came to the United States on a spousal visa from Bangalore, India, has the unusual distinction of maintaining a studio in the same building where she interviewed for citizenship. She received a green card in 1994 and citizenship in 1999. In 2015, Krishnan became a full-time artist.

When Krishnan had her studio at Inscape, her neighbors included printers, tarot readers, theater companies, and the Tibetan Nuns Project. The building has housed the workspaces of such high-profile Seattle creatives as Lindy West, author of Shrill, and Nate Gowdy, a photographer known for his images of 2016 presidential candidates. Just a block or two from CenturyLink Field and the landmark Uwajimaya market in Chinatown, artists can rent studios starting at $1.10 per square foot.

Jeff Babienko, an architect who emigrated from Canada, also received his green card in the old INS building. Babienko is of Ukranian descent and had a very similar experience to Krishnan’s. “I had to wait in line in the rain like everyone else,” he says. The room where he was interviewed for his green card is now a theater.

Babienko and his architecture firm are now housed in the Inscape building, and he says that he loves the community and collaborative spirit that the building fosters. “We were some of the first to move in,” he says. “We had a hand in designing our own space.” He also appreciates the construction of the building itself: The pilings are so effective in Seattle’s coastal soil that the building has stayed at virtually the same elevation since its construction, even as a walkway out front sank over time.

Some of the art here takes the Inscape Building’s difficult history as a starting point. Christian French installed “The INS Game,” a set of satirical board game squares, in the floor of various hallways. These Monopoly-style game squares include instructions such as, “National Holiday. Sing the national anthem or lose a turn.” “No clerks speak your language. Lose a turn.” “Your name appears on a terrorist watch list. Draw a legal card. Lose 2 turns.” The squares are now so worn from foot traffic that some visitors wonder whether these were actual messages on the floor of the former immigration center.

A few blocks to the northeast, the Wing Luke Museum houses an archive of immigrant stories and collaborated with Inscape on an installation, Voices of the Immigration Station: 72 Years of Immigration on 5 Floors. The partnership kept these voices alive in several installations. Detained, a nonfiction graphic novel by Eroyn Franklin, preserves the stories of Many Uch from Cambodia and Gabriela Cubillos from Mexico. Metal panels throughout the building record the stories of the named and nameless. The panels have a matte finish that does not reflect much light; the image of the onlooker, like the identities of many who have been detained or deported, is erased by the metal.

In the Inscape Building basement, printmaker Elisa Dore created woodcuts and screenprints as part of Print Zero Studios co-op (though she now works out of her home). “It’s impactful to be aware of the history, not to just be in a nameless building,” Dore says. Born and raised in Atlanta, Dore’s work focuses on feminine and specifically Latina experiences. “When I was a kid my mom used to tell us, ‘You’re half Puerto Rican,’” Dore goes on. “My family used to ask me, ‘Which half?’”

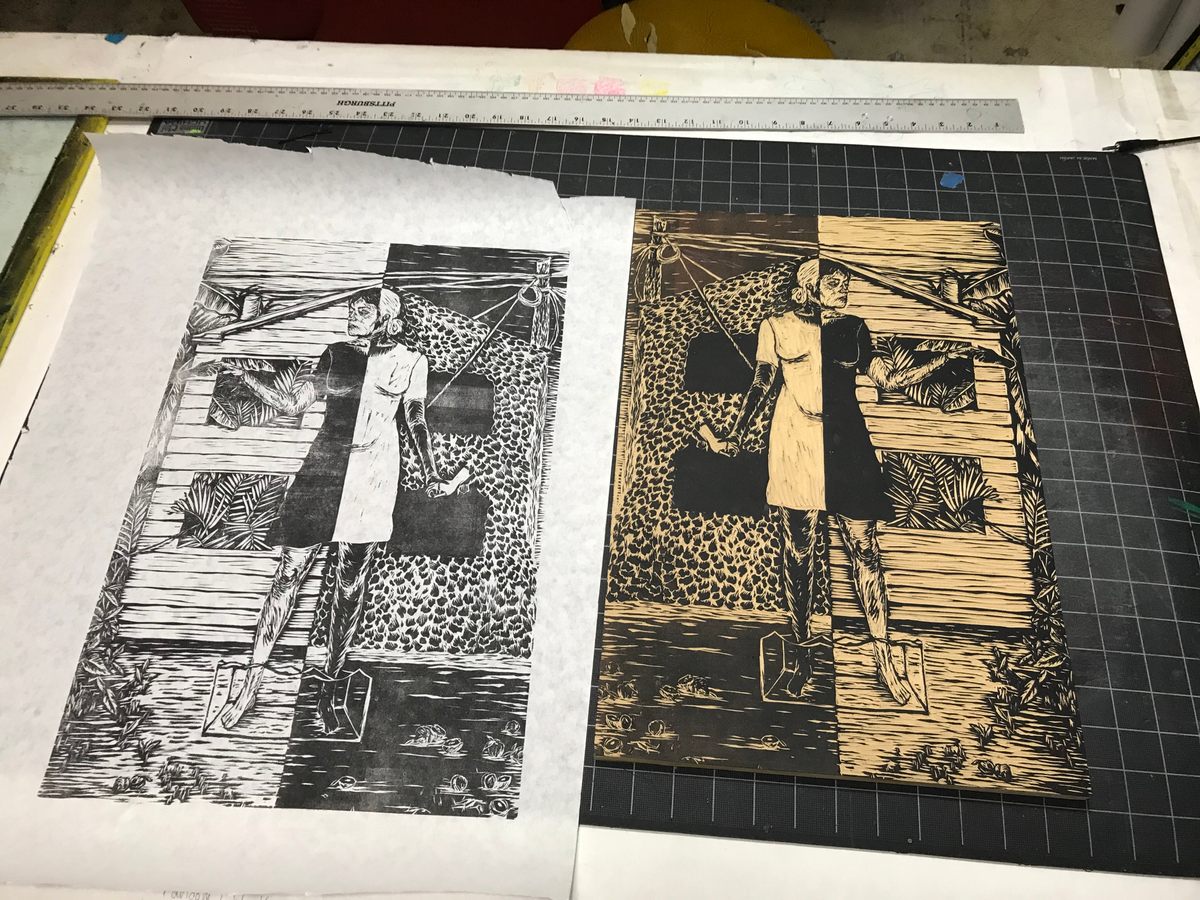

For one project, Dore created prints from a woodcut depicting a woman, dressed simply and standing in front of a modest house. In a touch of surrealism, tropical fronds grow into and out of the house, but only on one side. The composition is nearly symmetrical, cut down the middle by a stark line. What’s white on one side of the image is black on the other.

The building retains many other reminders of incarceration. A yellow line runs the length of a dank hallway in the basement; according to Mike Donnelly, the building manager, this marked the queue where people would stand for “processing.” Decades of graffiti, mostly names and nations of origin in a myriad of languages, can be found on a courtyard wall. Signs throughout the building mark locations such as “Confiscated Materials,” “Control Room,” and “Detention Cell.” One of the most harrowing historical features is that of two painted handprints on the wall. Here, immigrants were searched as they placed their hands in the designated space and spread their legs. The building, like so much of Seattle and the surrounding area, still exists on Duwamish tribal land that was occupied without treaty.

Krishnan, who is self-taught, went to the Inscape building because she was dissatisfied with her former studio; it had no ventilation or windows, which limited the paints and other materials she could use. “I did not remember that this was the same building until I applied,” she says. “When I got here, that’s when I realized that I’d been here a couple times before.” For an oil series, nine dancers posed for Krishnan, each exemplifying a different emotion. Krishnan frequently paints portraits of Asian women, pointing out that they remain underrepresented in the art world.

Although she says the building’s history has been meaningful to her, it’s not a direct inspiration for her work. She seems far more interested in the building’s present—a common sentiment among the Inscape residents, past and present. “There are so many creative people in this building,” she says, “and everyone’s busy doing something.”

This story originally ran in 2020; it has been updated for 2023.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook