The Weird and Very Long History of State Liquor Laws

It’s about control.

(Photo: Tripp/CC BY 2.0)

This week, Pennsylvania enacted its biggest liquor law reform since Prohibition, which will soon enable its residents to, among other things, get wine directly shipped to their homes from wineries out of state.

Pennyslvania’s laws on booze had been, up until recently, among the country’s most restrictive, in part due to the state’s Quaker heritage, and the penalties for importing wine under the old laws could get very, very serious. A judge in the state last year, for example, ordered over 1,300 bottles of wine to be poured down the drain to penalize a man who allegedly illegally imported the wine from California and Germany, among other places. (He struck a deal to keep 1,000 other bottles.)

Elsewhere, America’s liquor laws don’t get much more rational. In Massachusetts, for example, happy hours are illegal. In Utah, home to the country’s most specific prohibitions, no beer on tap can be more than 4.0 percent alcohol, you have to order food with your booze at restaurants, you can’t order doubles, and, for restaurants open after July 2012, cocktails will be mixed only out of the sight of customers. In Maine, you can’t buy a drink after 9 a.m. on Sundays, except when that Sunday happens to be St. Patrick’s Day. In Louisiana, you can buy a daiquiri in a drive-through but can’t drive with it if a straw is inserted into the cup. In Nevada, you can drink pretty much anywhere and public drunkenness simply isn’t a crime.

Around the world, regional regulation like this is seldom seen. In Germany, beer purity regulations are encoded in the country’s law books. Alcohol is banned throughout all of Saudi Arabia, and in many other Muslim-majority countries. Other countries, like France, take alcohol to be a huge (if fading) part of their national identity, and encourage moderate, everyday drinking for healthy living .

So why is the U.S. different? You can blame the Founding Fathers, for one thing, since they didn’t care to address the issue in the Constitution, leaving states to decide how to handle it. But you can also blame our country’s long, complicated, and polarized relationship with alcohol.

For centuries, Americans have drank, and drank, and drank, often at rates far surpassing other countries. If France, for example, can be personified as a refined couple at a table sharing a bottle of Beaujolais, the U.S. is the drunk at the bar taking shots and making a scene, and every so often forcing the cops to show up. But the widespread overindulgence has also inspired repeated and successful campaigns for temperance, culminating with Prohibition, a 13-year legal ban on making and selling alcohol in the U.S. that ended in December 1933.

Prohibition wasn’t the first time buying booze was made illegal in America, though. The first bans, on the state level, were enacted decades before, and laid the groundwork for the wildly inconsistent mishmash of liquor laws we have today. Indeed, the Prohibition Party is the oldest third party in America, although it has never received more than 2.2 percent of the popular vote, since first appearing on the ballot in 1872.

Most of today’s laws about alcohol are rooted in a sort of puritanism, but, as the years go by, many also begin to take on their own inertia. Why can’t you buy a refrigerated beer of more than 3.2 percent alcohol in Oklahoma? No one knows! But, in 2016, the state is still having a really hard time changing that.

At any rate, it’s clear this mess might have been inevitable from the beginning.

In the decades after the Revolution, according to ”Liquor Laws and Constitutional Conventions: A Legal History of the Twenty-first Amendment” by Ethan P. Davis, most Americans drank all day, everyday, in a time when the best way to get your baby to stop crying was to put some liquor in its bottle.

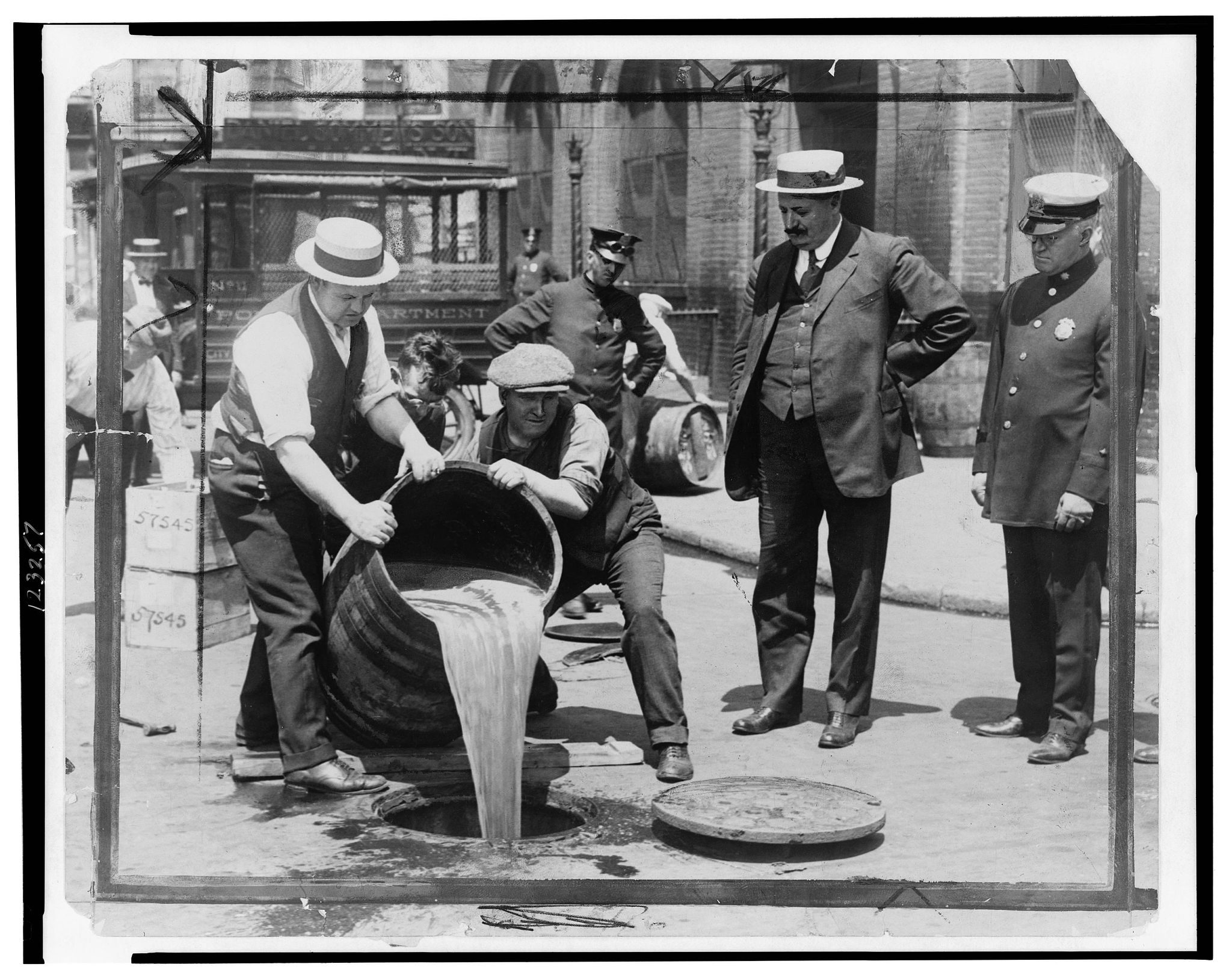

Pouring out alcohol during Prohibition. (Photo: Public Domain)

The first state, in fact, to make the sale or manufacture of booze illegal was Maine in 1851, mainly spurred by temperance advocates who were horrified by American drinking, Davis writes. Other states enacted similar laws, but most of these laws seem to have disappeared by the time of the Civil War; America probably needed a drink.

Still, the drive for temperance picked up again after Reconstruction ended in 1877, and dozens of states began outlawing the manufacture and sale of booze. But there was only one problem: they couldn’t stop it from being imported from other states, and, in 1898, the Supreme Court ruled that it was an American’s constitutional right to buy imported alcohol, no matter what state they were living in.

And so the conflict continued, with the temperance movement continuing to pick up steam, spurred on in part, Davis notes, by anti-German sentiment stoked by World War I. Millions of German immigrants had brought their beer-drinking culture to America, setting themselves up to be partly blamed for the country’s drinking problem. There were also temperance radicals, like Carrie Nation, an activist who carried out a campaign of attacks on saloons, in which she would walk in and start smashing things with a hatchet.

In 1919, the Eighteenth Amendment passed, and, a year later, Prohibition formally began. The next 13 years were a well-documented American disaster, with the rapid rise of bootlegging and organized crime; just seven years after Prohibition began there were calls to repeal it, and, indeed, by 1933, Prohibition was officially dead.

Happily drinking in 1938 after Prohibition’s repeal. (Photo: Public Domain)

And that’s where, on a state level, things got more interesting, since states were once again free to regulate alcohol as they saw fit. In the years after Prohibition’s repeal, many states opted to form monopolies, in which only state-run stores sold liquors; over two dozen others set up complicated licensing systems for liquor sales, and a handful of states decided to stay dry. Every state eventually turned wet in some form, with Mississippi being the last in 1966.

This was all, in fact, by design, because Congressional debate on alcohol always made one thing clear: as long as it was legal, it would be left up to state control. This was in part because of the divide between the pro-alcohol wets, who tended to live in cities, and the anti-alcohol drys, who tended to live rurally. Local control was important. But this also made it inevitable that the system would produce quirks. Or merely anachronisms, like South Carolina’s former ban on buying booze on Election Day, which was originally intended to reduce bribery from a time, 130 years ago, when bars sometimes served as polling places.

So think about that when you’re at your regular spot in Iowa, and the bartender won’t let you keep a running tab. Some lawmakers once thought about that, and probably debated it for awhile, and then made a very considered decision.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook