The Prohibition Party Still Exists–And Is On the Ballot In At Least 3 States

Progressive cred, theatrical candidates, and a weird, bipartisan platform–the oldest third party in the country has it all.

Gene Amondson, a recent Prohibition Party presidential candidate, wielding a chainsaw in homage to radical temperance pioneer Carrie Nation. (Photo: Rick Dahms/CC BY-SA 3.0)

In this divisive election cycle, as Republicans and Democrats fight tooth and nail for votes, it can be easy to forget that there are other options.

Maybe you’d prefer to throw your weight behind a party that supported women’s rights decades before the others, proposing an equal pay amendment way back in 1892. Maybe you’re intrigued by conventioneers who, as recently as 2008, nominated a presidential candidate best known for standing outside wineries dressed as the Grim Reaper. Or maybe you’re looking for a platform that combines second amendment hawkishness with climate change awareness, and chases it all down with a nice glass of cola. Meet the Prohibition Party–the original alternative to politics as usual.

The Prohibition Party is the oldest third party in America. Even though it has never drawn more than 2.2 percent of the popular vote, it has shown up on every presidential ballot without fail since 1872. While it has occasionally participated in a showstopper, like the 1920 nationwide alcohol ban that bore its name, it is generally content to chug along in the background, its long-lasting presence victory enough. Over its 147-year tenure, its outsider stance has manifested in an astounding variety of ways.

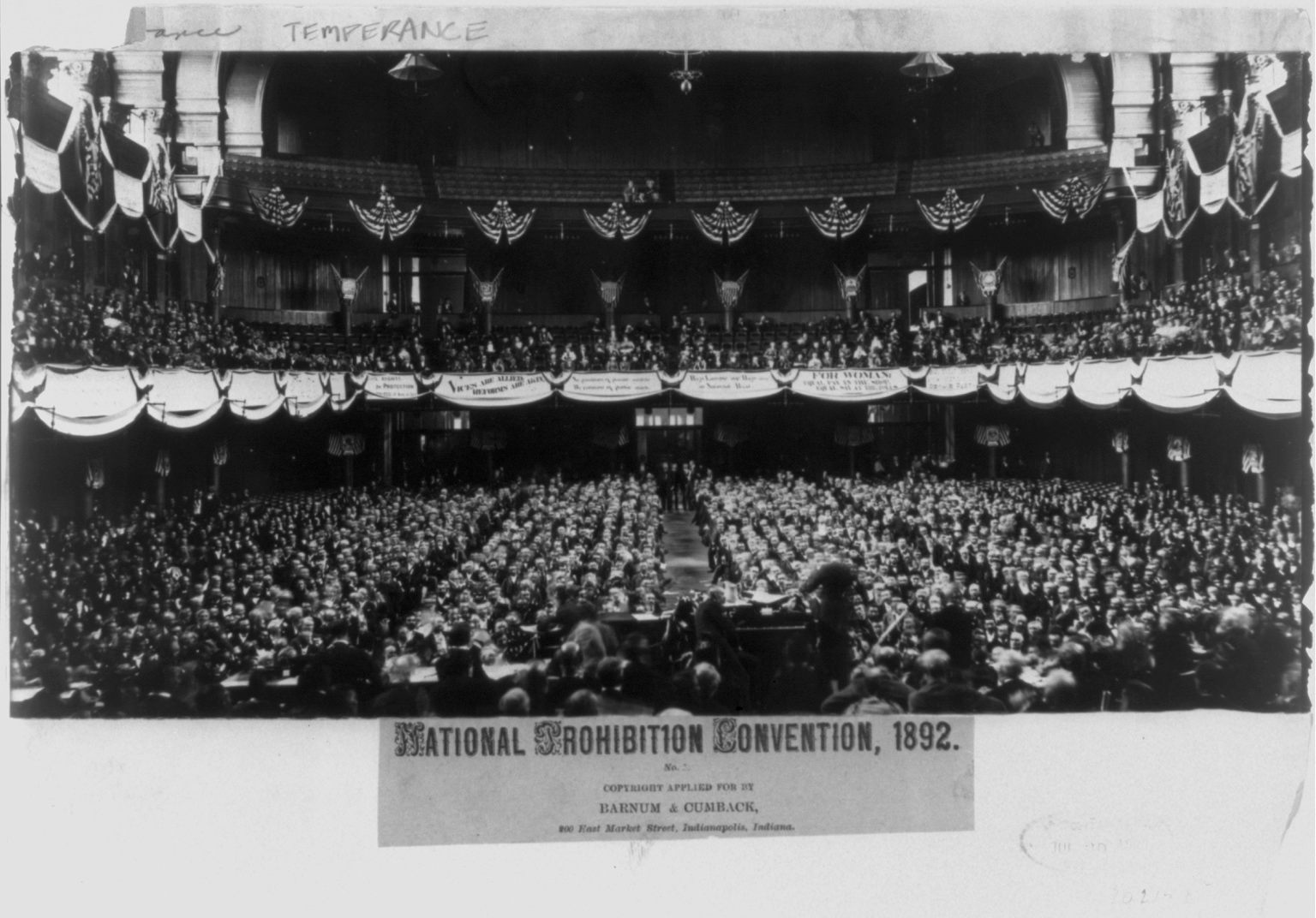

The well-attended National Prohibition Convention in Cincinnatti in 1892. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-59668)

“I think hardly anybody knows about us, and that most of those who do think that we’re a one-party issue because of the name,” says Jim Hedges, Executive Secretary of the Prohibition Party. Hedges has been a proud Prohibition Party member for half a century, and is their presidential candidate for 2016. He describes his party as a piece of “living history,” and starts his emails “Thanks for noticing the Prohibition Party!”

Although the party’s signature issue is, and always has been, the prohibition of alcohol, it “has always been interested in social reform more broadly,” Hedges says. He sees its continued existence as “an opportunity to do some teaching and to create some public awareness” about history, temperance and social reform.

The Prohibition Party was founded in 1869, by a coalition of “temperance advocates and former abolitionists,” writes historian Lisa Andersen. Just as Trump paints the establishment as critically weak on immigration, or Sanders’s cascade of wide-ranging proposed solutions stems chiefly from financial reform, early Prohibition Party members saw, in 19th-century alcohol policy, both major parties’ major failings. In the Prohibitionists’ eyes, the alcohol industry “infiltrated the Democratic and Republican parties by offering bribes and threatening to withdraw votes,” Andersen writes. Not only that, drinking frayed the very fabric of democracy by “destroy[ing] a voter’s ability to recognize his self-interest.”

The Prohibition Party championed women’s rights a full half century before they even had the legal ability to vote. Many women, in turn, found that the party’s platform of temperance aligned with their moral and economic values. From the party’s founding, female members “spoke from the floor, entered debates, introduced resolutions, and voted on the party platform,” writes Andersen.

Long before Hillary Clinton named equal pay for women as one of the main social issues she would tackle as president, the Prohibition Party’s 1892 platform included a call for equal pay between genders. In 1896, suffragette Elizabeth Cady Stanton endorsed the Prohibition Party, declaring that “no woman with a proper self-respect can any longer kneel at the feet of the Republicans.”

An 1887 portrait of Susanna Madora “Dora” Salter, the first woman to hold elected office in the U.S. (Photo: Kansas Historical Society/Public Domain)

Susanna Madora Salter, the first female elected political official in America, was a Prohibition Party candidate when she was sworn in as mayor of Argonia, Kansas, in 1887. Originally nominated as joke, she won handily. Susan B. Anthony congratulated her personally, reportedly slapping her on the back and exclaiming “Why, you look just like any other woman!”

In 1924, the Prohibitionists also became the first to put a woman on the presidential ballot when they named Marie C. Brehm as their vice presidential candidate. The New York Times registered the pioneering nomination with a tellingly broad headline: “DRYS NAME WOMAN FOR VICE PRESIDENT.”

Through the early decades of the 20th century, the Prohibition Party slowly built up local and national support. They managed to elect a governor, Florida’s Sidney J. Catts, and a three-term Congressman, California’s Charles H. Randall. From 1900 through 1916, they consistently drew over 200,000 votes in Presidential elections–small potatoes in the scheme of things, but not bad for a third party.

The Party’s biggest coup was, of course, Prohibition–the thirteen-year stretch, beginning in 1920, during which “the manufacture, transportation, and sale of intoxicating liquors” was outlawed in the United States. (This was not due entirely to their efforts–other temperance groups, such as the Anti-Saloon League, played a greater role–but they certainly helped out.) Paradoxically, this success meant that many of the party’s supporters fled, considering their work finished. “With the coming of prohibition the party has shrunk to nothing,” wrote New York Times editorialist Charles Willis Thompson in 1920.

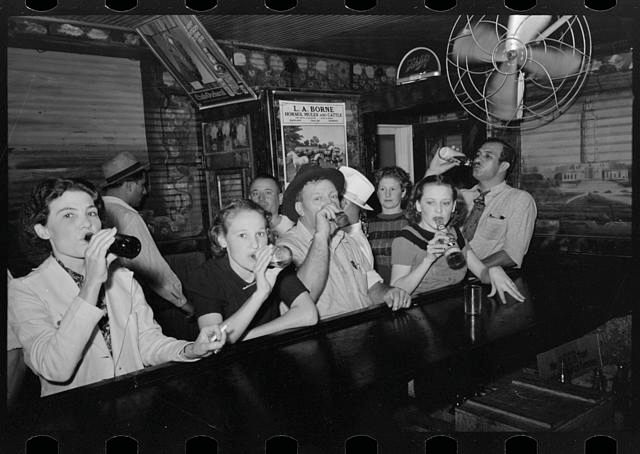

Men and women drinking together after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. Photo by Russell Lee. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USF33-011654-M4)

With the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, and the start and finish of the Second World War, the party’s support continued to dwindle. Their presidential vote totals shrank into the tens of thousands, and then into the hundreds. Their base’s demographic shifted, too: the exodus of progressives and the lack of new youth enrollment “left the party in the hands of religious conservatives whose denominations forbade drinking,” says Hedges. To this day, Baptists and Methodists remain the group’s core support.

This massive switch, along with the party’s unique agenda, has meant recent Prohibition Party presidential candidates really run the gamut. Gene C. Amondson, the party’s 2004 and 2008 presidential nominee, spent his pre-politics years touring the nation reenacting Billy Sunday sermons and visiting wineries dressed as the Grim Reaper. (He was also known to honk twice every time he drove past a tavern.) Jack Fellure, the 2012 nominee, ran on a platform that consisted only of “the Authorized 1611 King James Bible.”

Hedges has the distinction of being the first Prohibition Party candidate in this century to hold any office at all: he was the Tax Assessor for his township in Pennsylvania from 2002 through 2007. Though he downplays it–“it’s a very minor local office, and there was no opposition”–this, combined with his tenure as Executive Secretary, has given him some power. He describes himself as “the left wing of the Prohibition party,” and has used his relatively high position to muscle in some more liberal planks.

The Prohibition Party’s current homepage. (Screenshot courtesy: prohibitionparty.org)

These tensions–between the past and present; between individual opinions and collective influence–have resulted in a Prohibition Party platform that, even in today’s political climate, appears somewhat schizophrenic. Calls for free college education and climate change legislation nestle alongside strong statements against gun control and same-sex marriage. Proposals to raise the minimum wage coexist with appeals against the federal health care system. The party that once boasted more female members than men in major cities now holds a strong anti-abortion stance.

Then, of course, there is still the call for prohibition itself, now expanded to include current recreational drugs. It’s difficult to imagine that anyone who is attracted by some of these positions won’t be utterly repelled by others.

Talk to their top brass, though, and you get the sense that this doesn’t matter all that much. Like their forefathers, 21st-century prohibitionists are playing the long game. Hedges, who turns 78 this year, is not much of a campaigner. There’s no money to send him around the country. Ask him to pretend he’s making a stump speech, and says, “if a bunch of guys sit around and get smashed and then try to draw up a policy, it’s difficult to get it right”–which, while undoubtedly true, isn’t much of a peg to hang a “Make America Dry Again” hat on.

Last year, for the first time in the party’s history, their convention was held not in a civic center or chain hotel, but over conference call. “There wasn’t much enthusiasm for going anywhere,” says Hedges.

Instead, for the 2016 election season, Hedges is focusing on getting on the ballot in as many states as possible, a difficult process for third parties. So far, they’re on there in Colorado, Arkansas, and Mississippi, and are trying for Florida, Iowa, New Jersey, South Dakota, and several others. He expects the usual number of protest votes–”people will say ‘a plague on both their houses’ and vote further down the ballot,” he says–which, if multiplied through enough states, could garner them about ten thousand votes. (Last year they got only 512.)

“If we can demonstrate to the public again that we’re a going concern and a serious party by getting a lot of states this time,” he says, “I hope that people will come out and vote for us because they realize that it does make a difference.” At the very least, it keeps a bit of unique living history with us for one more year.

Update, 3/6: The original version of this article said that Jim Hedges was the tax assessor for his county; he was actually tax assessor for his township. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook