The Medieval Prophetess Who Used Her Visions to Criticize the Church

Hildegard of Bingen fought the patriarchy from her cloister.

A depiction of Hildegard von Bingen. (Photo: Zvonimir Atletic/shutterstock.com)

Recently, groups of progressive nuns have become increasingly vocal in their opposition to the patriarchy and regressive social views of the Catholic Church. However, few have ever openly dressed down their church elders, or called a world leader a “juvenile fool.” This honor is held by Hildegard of Bingen, the brash and brilliant medieval abbess, author, herbalist, composer, prophetess and visionary who ruled her own monastery of Rupertsberg, high on a hill in rural Germany.

Hildegard’s teachings, opinions, and prophecies, told through “visions” she referred to as both “illuminations” and “reflections of the living light,” compelled hordes to people to visit her, and made her a force to be reckoned with in the power circles of 12th century Europe.

Hildegard was born around 1098, in the Rhineland-Palatinate region of Germany. The tenth and last child of wealthy parents, Hildegard felt different from an early age. “I was only in my third year when I saw a heavenly light which made my soul tremble,” she would later write. “But because I was just a child I could not speak out.”

These visions, which Hildegard claimed to experience while fully awake, with open eyes, terrified the young child. “When I became exhausted I tried to find out from my nurse if she saw anything at all other than the usual objects,” Hildegard wrote. “She answered, ‘nothing,’ because she saw nothing like I did. Then I was seized with a great fear and did not dare to reveal this to anyone.”

The remains of the monastery Disibodenberg. (Photo: saharadesertfox/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Perhaps because of her sensitivities, or as part of her noble family’s tithe to the church, Hildegard was “enclosed” as an anchorite, along with a teenager named Jutta, at the remote Benedictine monastery of Disibodenberg when she was still a child. Anchorites were metaphorically “buried” in a small cell or structure attached to a monastery or church. They were often given food through grilles, and were allowed little or no communication with the outside world.

The charismatic Jutta soon became famous throughout Germany for her holiness, sage wisdom, paperwhite skin and frail, ethereal appearance. This fame attracted male and female seekers and rich would-be-nuns to Disibodenberg, and within a few years the metaphorical “sepulcher became a kind of monastery,” with Jutta as its official abbess. Jutta took Hildegard under her wing and treated her as a daughter.

For the first half of her life, Hildegard essentially served as Jutta’s right-hand woman. In 1136, an emaciated Jutta died, and Hildegard, long in her shadow, became Disonbodenberg’s unofficial abbess. She continued to have visions, which were usually accompanied by dreadful bouts of illness, but kept them a secret from almost everyone. This changed in 1141, a moment which Hildegard described in Scivias (Know the Ways), her first book:

And behold, in the forty-third year of my passing course, while I was intent upon a heavenly vision with great fear and tremulous effort, I saw a great splendor, in which a voice came from heaven saying to me: ‘O weak mortal, both ash of ash and rottenness of rottenness, say and write what you see and hear. But because you are fearful in speaking and simple in explaining and unlearned in writing these things, say and write them not according to human speech nor the understanding of human creativity…speak the things you see and hear; and write them not according to yourself or any other person, but according to the will of the One Who knows, sees, and disposes all things in the hidden places of his mysteries.’

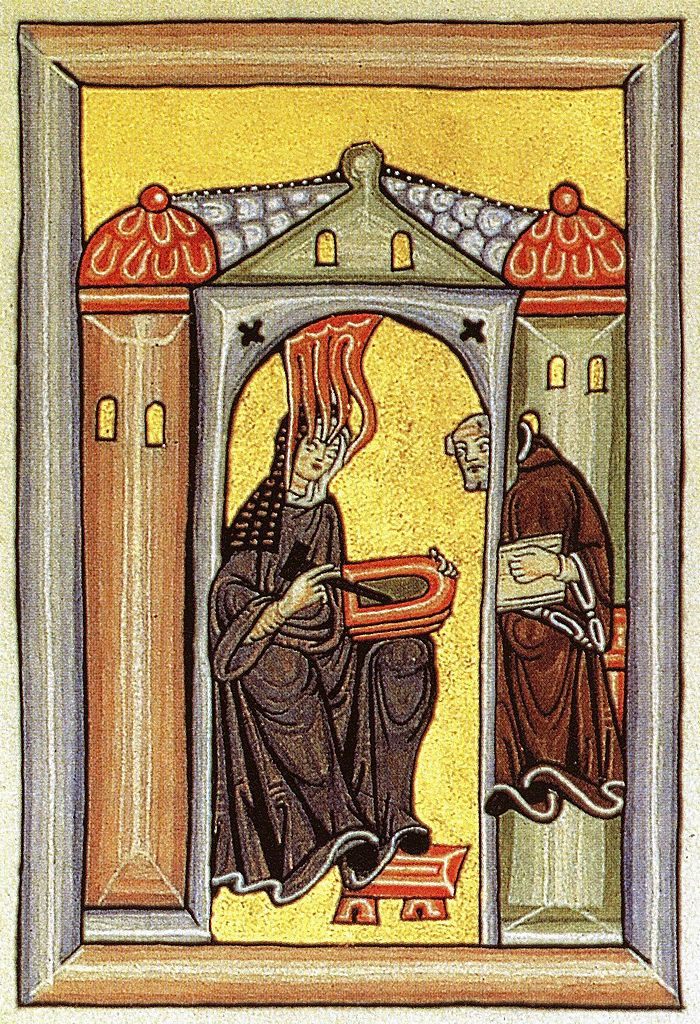

Hildegard shown receiving divine inspiration. (Photo: Public Domain)

Hildegard, always obedient to the “voice” she believed was of God, began to write down her visions and thoughts on wax tablets. Her friend, the monk and scribe Volmar, would then translate her writings into proper Latin. In 1147, Pope Eugenius III, presented with the first parts of Scivias, declared Hildegard’s prophetic writings authentic and important works.

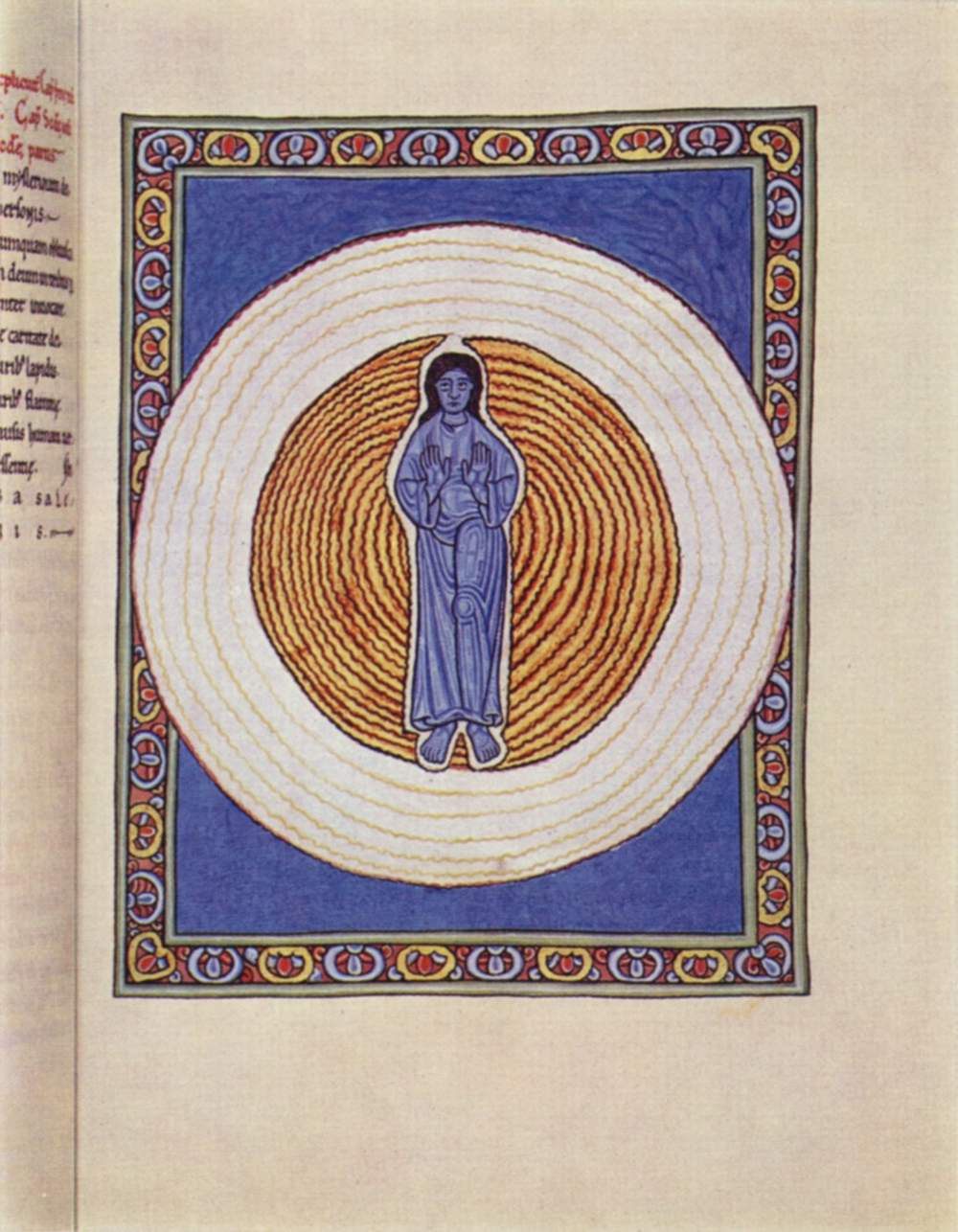

These 26 visions are at turns beautiful, brutal and confounding. The most famous version of Scivias, produced at Hildegard’s new monastery of Rupertsberg, includes artistic renderings of her visions. Although it is unknown if Hildegard painted the interpretations of her visions herself, there can be little doubt that she at least oversaw their creation. Their strange composition, along with Hildegard’s descriptions of the showers of light, wavy lines, and pain that accompanied her visions, have caused neurologists like Oliver Sacks to believe she may had suffered from severe migraines or temporal lobe epilepsy. (The original codex, lost since World War II, was painstakingly recreated by nuns in the 1920s.)

Hildegard’s biographer Barbara Newman believes these visions were a canny way to have a voice in an overwhelmingly patriarchal society. According to Newman, Hildegard used “visionary style and prophetic authority as modes of empowerment for a woman who would otherwise have no license to speak—let alone write or preach—about the things of God.” Although she was a great supporter of women, and in many ways a proto-feminist, Hildegard often railed against the “womanish time” she was living in, where a spineless church and evil state tussled over prestige and power.

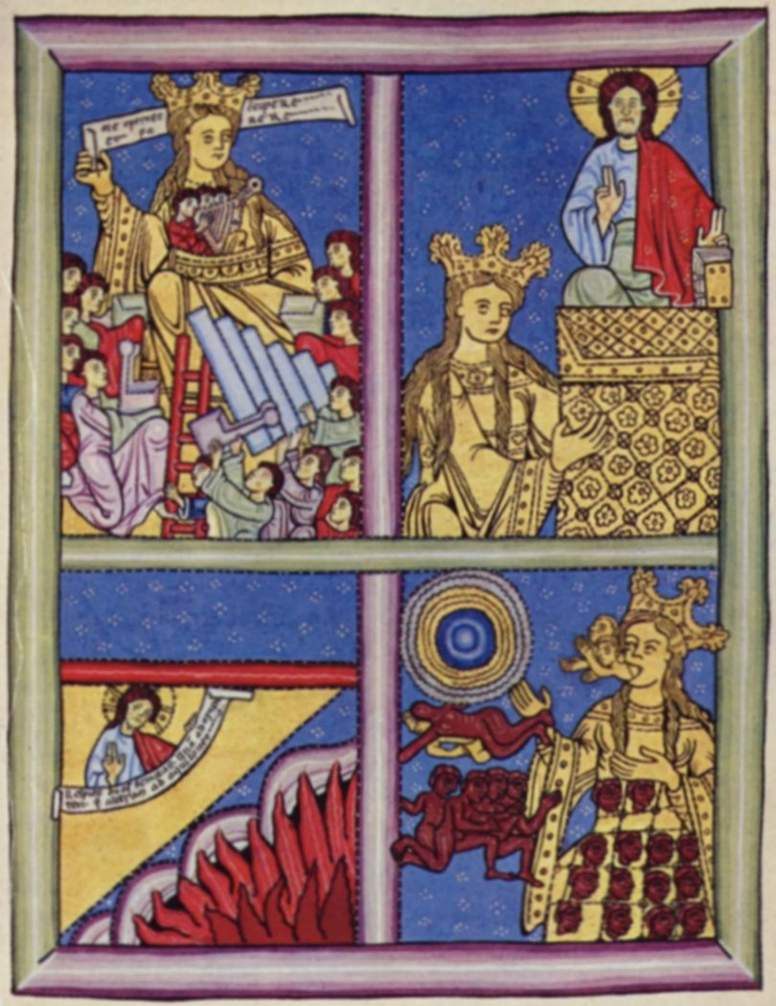

Motherhood in the spirit and the water, also from the Scivias. (Photo: Public Domain)

Take for example, one of the most horrifying illustrated visions in the Rupertsberg codex, that of a woman with a monster protruding from her nether-regions during the end of times:

And from her waist to the place that denotes the female, she had various scaly blemishes; and in that latter place was a black and monstrous head. It had fiery eyes, and ears like an ass’, and nostrils and mouth like a lion’s; it opened wide its jowls and terribly clashed its horrible iron-colored teeth. And from this head down to her knees, the figure was white and red, as if bruised by many beatings; and from her knees to her tendons where they joined her heels, which appeared white, she was covered with blood. And behold! That monstrous head moved from its place with such a great shock that the figure of the woman was shaken all through her limbs. And a great mass of excrement adhered to the head; and it raised itself up upon a mountain and tried to ascend the height of heaven.

This vision was seen as a thinly veiled attack on the Catholic Church. The woman was the Holy Mother Church, but the monster–literally Satan–represented the reformists and corrupt officials that Hildegard believed were destroying the one true faith. Always a reactionary in terms of church politics, Hildegard was disgusted by reformist religious sects and the money grubbing of the Catholic Church. This vision was a way to warn her readers to support her version of Catholicism–or the end of days would soon be upon them.

Rupertsberg monastery, shown c. 1620. (Photo: Public Domain)

Hildegard also used her visions and supposed mystical powers to buck tradition in more practical ways. In 1148, as her celebrity and religious order grew, Hildegard claimed to have had a vision in which God directed her to leave Disibodenberg Monastery and build a new monastery atop the nearby Mount of St. Rupert. When the church elders, wary of a woman leading her own establishment and unhappy with losing the revenues brought by her fame, refused to grant her permission to leave, she fell into a grave sickness. Fearful for her life, the elders finally relented. Miraculously, Hildegard “rose up very sprightly as if she had not at all been disabled for so long a time.”

Rupertsberg Monastery opened around 1150, and quickly became a self-sufficient complex. At Rupertsberg, Hildegard used her visions to challenge long-standing traditions that she did not agree with. When critics complained that Hildegard allowed the 50 or so nuns at the Romanesque complex to dress resplendently in white, their hair worn long instead of shorn, Hildegard replied that God himself had directed her to do it, writing: “I saw that a white veil to cover a virgin’s hair was to be the proper emblem of virginity.”

With her widely recognized “gift” as ammo in her pocket, Hildegard became an advisor and honest critic of Kings, Queens, Emperors, Popes and priests. Over 400 of her letters survive, and according to biographer Fiona Maddocks, they offer fascinating insight into the different ways she portrayed herself. To men, she was but a poor, frail woman, who was speaking what God had told her. In her correspondence with women, she was much more straightforward and honest, often dispensing practical advice from one of her many areas of expertise.

From the Scivias: The true Trinity in true unity. (Photo: Public Domain)

A true Renaissance woman, Hildegard would leave behind an astounding body of work. She composed over 80 songs for her “virgins” to sing in the monastery chapel. She founded a second monastery. She wrote Causae et Curae and Physica, which offered common sense nutritional and medical advice, listed thousands of herbal remedies, and discussed sexuality in, at times, surprisingly modern terms. She would go on four speaking tours in her later years, where she denounced the corruption of the church to co-ed crowds, an almost unheard of act for a woman of her time. Most mysteriously, she made up her own language, which consisted of over 900 words and an alternate alphabet.

After one last victorious fight with her clerical superiors, during which she accused them of being “ensnared by Satan,” Hildegard fell seriously ill. She died at Rupertsberg on September 17, 1179, at the age of 82. Her contemporary biographer, Guibert of Gembloux, wrote that as the canny, brilliant prophetess lay dying the mountaintop was showered with a light show consisting of a giant red cross, multi-colored circles and smaller crosses.

“It is worthy of belief,” Guibert wrote, “that by this sign God was showing how bright was the splendor with which he was illuminating his beloved one in heaven.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook