The Fascist Building in Upper Manhattan

The Casa Italiana has a complicated history on Columbia University’s campus.

Casa Italiana at Columbia University. (Photo: Another Believer/CC BY-SA 3.0)

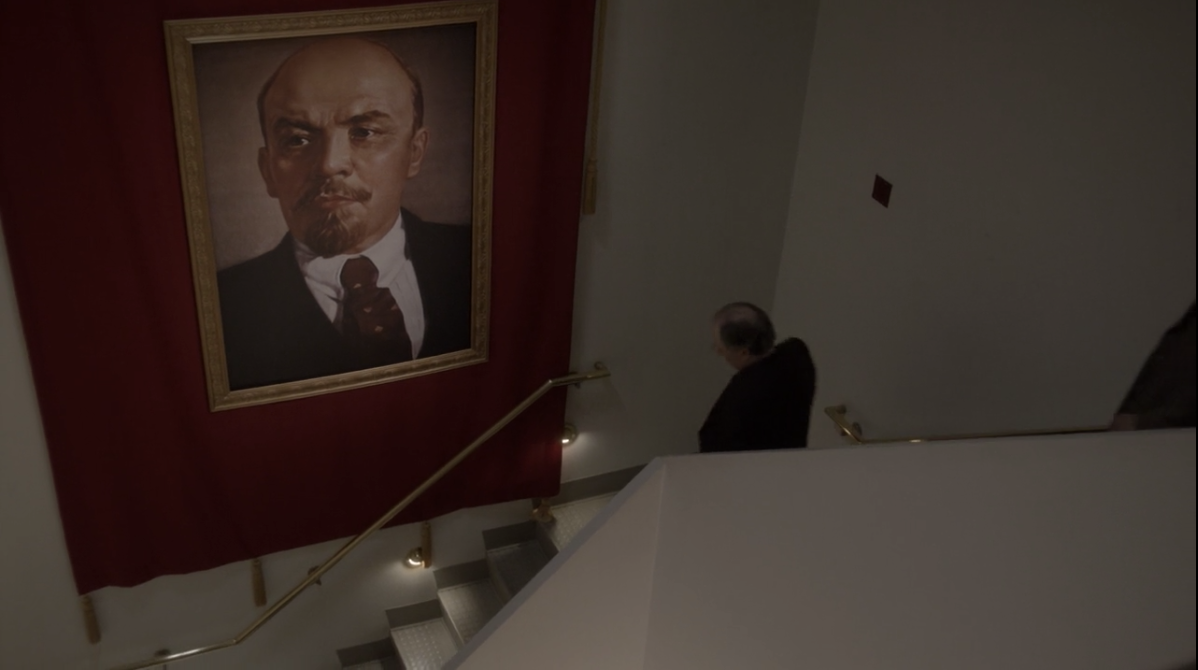

Columbia University’s Casa Italiana is most recognizable today for a star turn in FX’s spy thriller The Americans. While a carefully-constructed soundstage lookalike is used now, the Casa served as the original filming location for the show’s opulent Soviet Rezidentura. Its real-life history might be as interesting as its onscreen identity, though: the stately Casa currently hosts a renowned research institute—but the uptown Manhattan building has a history of political intrigue that’s little known outside the ivory tower.

Built in the tumultuous 1920s and intended to promote Italian culture in the United States, the Casa Italiana was political from the start. According to a January 20, 1926, article in the New York Times, Italy’s Fascist prime minister Benito Mussolini was involved with the Casa even before construction began, having first learned about the project from Columbia instructor and General Secretary of the Institute of Italian Culture Peter Riccio in July of 1925. As the Times reported,

“The Prime Minister was enthusiastic over it, offering to equip the entire house with Italian furniture of various periods, paintings and art objects obtained from the old royal palaces of Italy.”

The stairwell in Casa Intalian, as shown in The Americans. (Photo: Screengrab/FX)

The Casa’s first political scandal took place in February, 1928, when a prominent anti-Fascist named Luigi Criscuolo publicly complained that every lecturer scheduled to speak at the Casa had Fascist sympathies.

Just four months earlier, the Casa’s Columbus Day opening ceremonies had been presided over by radio technology pioneer and Fascist party official Guglielmo Marconi.

Annet Mahendru as KGB agent Nina in the Casa’s library from Season 1, Episode 4. (Photo: Screengrab/FX)

Columbia’s president Nicholas Murray Butler dismissed Criscuolo’s allegations, writing:

“The university does not permit itself to be used for what it has become fashionable to call propaganda of any kind, nor would it under any circumstances take part in or foment the partisan discussion of the international politics of any State or nation.”

Regardless of the truth of Criscuolo’s allegations, American support for Fascism was widespread when the Casa opened. In fact, a 1932 documentary about the Prime Minister titled Mussolini Speaks became a runaway hit with American audiences, who earnestly admired how Mussolini’s Fascist party had tackled Italy’s economic and infrastructure problems head-on. As the decade progressed, however, American criticism of Fascism gained steam.

On October 5, 1934, the front page of Columbia’s student newspaper was dominated by an article about an upcoming anti-Fascist protest planned by university’s Socialist Club paired with a withering editorial by an Oxford University student, who begged President Butler to take a stand against Fascism.

Mussolini was enthusiastic about Casa Italiana. (Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-08300/CC-BY-SA 3.0)

The next month, prominent political magazine The Nation took Butler to task for continuing to support—or, at least, not to denounce—Fascism. In an article bluntly titled “Fascism at Columbia University,” an anonymous writer singled out the Casa Italiana:

“[I]t is rather surprising that Dr. Butler says nothing about, and therefore presumably is not aware of, the subtle Fascist propaganda within the walls of his own university. The center of this propaganda is the Casa Italiana… it has become an unofficial adjunct of the Italian Consul-General’s office in New York and one of the most important sources of Fascist propaganda in America.”

The Nation’s campaign didn’t sway President Butler immediately, but as the prospect of a second World War loomed ever closer, the Casa’s activities became less political. In the decades since, the allegation that the building had served as a covert Mussolini mouthpiece in the 1930s has come to dominate student rumors about and even academic discussions of the building. American intellectual historian John Patrick Diggins even called it “a schoolhouse for budding Fascist ideologues.”

Radio pioneer and Fascist party official Guglielmo Marconi. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-39702)

“It’s true,” says Dr. Barbara Faedda, the associate director of the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies, which has operated out of the Casa since the early 1990s, “that members of the Fascist regime enthusiastically came to visit the Casa. The Fascist government sent checks for the purchase of appliances. And the Casa worked with the Fascist government to arrange for student exchanges.”

This is only part of the story, however. Contrary to the claims made by Criscuolo in 1928, Dr. Faedda has come across evidence in the archives showing that visiting lecturers were far from unanimously pro-Fascist—Marxist and Jewish gatherings were also held in the building in the 1930s. These findings only make the building more intriguing to Dr. Faedda, who noted, “I think it is impossible not to be fascinated by this building and its history.”

Columbia President Nicholas Murray Butler in 1916. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Still, Mussolini’s connection to the Casa Italiana looms large in campus legend. “Some visitors ask to see Mussolini’s portrait,” Dr. Faedda told me, “and seem disappointed when informed that we have no such portrait.” Ironically, during the building’s on-screen run as the Rezidentura, one of the biggest changes The Americans’ set designers made to the building was to hang in the Casa’s marble stairwell an enormous portrait of another controversial 20th century leader, Vladimir Lenin.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook