The Fierce Female Warrior Who Fought Tasmania’s Colonizers

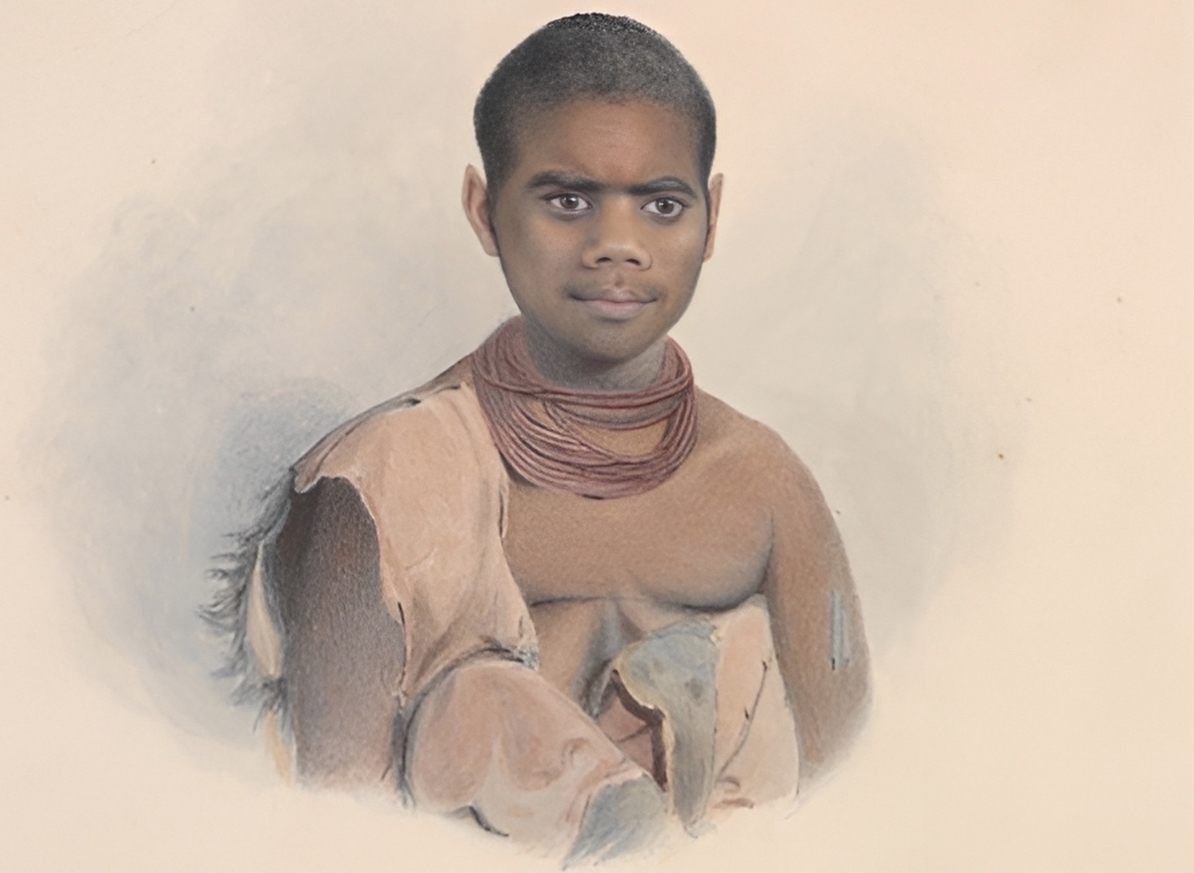

An Aboriginal woman from northwest Tasmania, Tarenorerer became one of the war’s most feared soldiers.

Excerpted and adapted with permission from Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of by Valorie Castellanos Clark, published March 5, 2023 by Chronicle Books. All rights reserved.

Like many Indigenous peoples’ stories, those of Tarenorerer were dismissed by colonizers. Large swaths of her record are lost to time. Even her name is often obscured by the name white enslavers gave her: Walyer. It’s hard to say why they changed her name to this. Perhaps it meant something to them; perhaps “Tarenorerer” was too hard for British fishermen and soldiers in the early 19th century to pronounce.

The parts of her story that we’re the surest about are the tragic parts: when and how she died. Languishing sick in prison, she died in late May or early June 1831, after most of her clan had been slaughtered by people who turned her homeland into sheep grazing land.

Tarenorerer was probably born in 1800. It’s commonly believed that she was a member of the Tommeginne clan, which joined at least seven other clans in northwest Tasmania—a large island that is part of present-day Australia—to form the North West nation. The Tommeginne was a maritime group that relied heavily on coastal resources. While the North West clans moved up and down the coast with the seasons, the Tommeginne spent most time at Table Cape, a peninsula in northwest Tasmania.

Ocher, a natural clay earth pigment, was sacred to the Tommeginne and used in both ceremonies and medicine. However, there wasn’t a lot of access to it in their region, so they built relationships with North nation clans to acquire it. Like any political relationship, these were always in flux; the Tommeginne clan was known for using its position at Table Cape for leverage in some of these relationships. (Table Cape provided easy access to Robbins Island, which North nation clans traveled to in order to hunt and gather shells. The Tommeginne clan could deny access if North nation clans refused to give them to ocher.)

Little is understood about Aboriginal spiritual beliefs or practices today because colonists didn’t record much of it, but we know that each of the roughly 100 clans had a designated animal as their totem. Indigenous people called the island they lived on Trowunna, a name often forgotten.

Tarenorerer grew up in the final years of this traditional lifestyle, though no one knew that was the case then. There’s little documentation of the perspective of the Aboriginal clans, but they probably knew of Europeans long before white people colonized Trowunna. Europeans had begun exploring Oceania as early as 1606, but the British were the first to establish a colony there, initially pushing Aboriginal people out of Botany Bay (now Sydney) in 1788.

Only 15 years later, in 1803, they expanded to the island of Trowunna. They called it Van Diemen’s Land, for Anthony van Diemen, a governor-general of the Dutch East Indies who had funded Dutch explorer Abel Tasman’s trip east. Tasman landed on the shores of Trowunna in 1642. (Colonists named the island Tasmania, after the explorer, in 1856.)

European sealers began using Van Diemen’s Land as a jumping-off point for their seal hunts in the late 1700s. They established mostly transactional relationships with the local clans they encountered, trading seal carcasses, tobacco, flour, and tea for kangaroo skins. This relationship was possible precisely because sealers weren’t there to stay and made no claim to the land. However, sealers were known to kidnap women from the North West nation for hunting seals and, one can guess, forced sexual relationships.

At some point before 1825, Tarenorerer was one of the many women kidnapped and enslaved by sealers. She was held against her will for years, though exactly how long is unknown. During this time, she learned English and how to use a gun.

While she was enslaved, colonists came to the island to live and cleared land for their sheep to graze on. This quickly brought them into conflict with the clans that had occupied the land for generations. European observers later documented that colonists “would shoot Aborigines whenever they found them,” leaving the clans no option but to defend their homes with violence. Individual skirmishes escalated into the Black War by the mid-1820s.

Sometime in 1828, Tarenorerer escaped her enslavers. She became the leader of the Plairhekehillerplue, a clan that lived around Emu Bay, southeast of Table Cape. Her position with the Plairhekehillerplue may be where the confusion around her birth clan comes from. Many clans had been decimated by colonial violence by the early 1800s, so the Plairhekehillerplue was likely a collection of people from many different clans.

Tarenorerer immediately began teaching clan members to use firearms to defend themselves from the colonists and to kill the colonists’ sheep and steers. She carefully instructed them to strike the colonial soldiers “when they were at their most vulnerable, between the time that their guns discharged and before they were able to reload.” During skirmishes with European shepherds, she would “stand on a hill and give orders to her men to attack the stockmen, taunting them to come out of their huts and be speared.”

At this time, Tasmanian Aboriginal clans began fighting each other for limited food and power. Challenged by other aspiring clan leaders, Tarenorerer escaped to Port Sorell on the northern coast with four of her siblings, some of whom the sealers had enslaved with her.

In 1829, Tasmania’s Lieutenant Governor, George Arthur, hired preacher and master builder George Augustus Robinson to try to make peace between the colonists and Tasmanian Aboriginal people whose lands they were stealing. The two British officials were heavily influenced by their evangelical beliefs and the antislavery discourse sweeping the British Empire; they firmly believed that the Tasmanian Aboriginal people were their “brothers in Christ” and should be saved from destruction by the colonists.

But their effort toward peace was far too little and far too late; the Tasmanian Aboriginal population had already been reduced to 1,000 people from an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 that had lived in Trowunna in 1803. Conflict was the main course of interaction by the time Robinson began his mission, and many people had given up hope of a peaceful solution.

Robinson kept a detailed account of his work and his concerns. He was more or less on the side of the clans who were being slaughtered. He believed that he could create peace by relocating Aboriginal people to missions or reservations on Swan Island, off the northeast coast of Trowunna, a trick he’d learned from the U.S. government’s treatment of Native Americans.

He negotiated for colonists to return land they had taken, as well as begged them to stop killing kangaroos for sport. In his journal, Robinson wrote, “[Aboriginal] children have witnessed the massacre of their parents and their relations carried away into captivity by these merciless invaders, their country has been taken from them, and the kangaroo, their chief subsistence, have been slaughtered wholesale for the sake of paltry lucre [money]. Can we wonder then at the hatred they bear to the white inhabitants?… We should make some atonement for the misery we have entailed upon the original proprietors of this land.” These notes were later sent to the King William IV and later published in 1966.

In his work, Robinson met Tarenorerer and recorded his thoughts about her. It’s largely through Robinson that we know she existed, though his logs are seen as problematic today due to their “white savior” perspective.

On September 20, 1830, Robinson records being stalked by members of Tarenorerer’s clan by the Rubicon River, near Port Sorell. He had heard of her and her warriors, who had been accused of committing violent acts against colonists. He wanted to capture them but thought that they intended to kill him; in the end, he didn’t try. By September 30, he wrapped up this journey around Trowunna without interacting with Tarenorerer’s clan.

By December 1830, Tarenorerer was captured and brought to Swan Island, where Robinson had set up reservations. She had been seized by sealers and taken to an island in Bass Straight, the body of water separating Tasmania from Australia. She refused to work for them, then attempted to kill the sealers while sailing with them one day.

According to James Parish, a sealer who became Robinson’s coxswain, Parish arrived just in time to save the sealers from Tarenorerer’s revenge and single-handedly took her away. The sealers were reportedly happy to give her up, but Parish’s story strains credibility. That he showed up in another ship just in time to single-handedly subdue a woman on her way to killing several sealers seems suspicious, but it’s the only recorded version of the story.

Tarenorerer was not immediately identified when she arrived at Swan Island. Robinson had not met her before this moment and learned who she was only because she was “given away by her dog Whiskey and by other Aboriginal women.” When he realized who the sealers had captured, Robinson recorded it as a “most fortunate thing that this woman is apprehended and stopped in her murderous career…The dire atrocities she would have occasioned would be the most dreadful that can possibly be conceived.”

Once ensconced on a Swan Island reservation, Tarenorerer began circulating a story that Robinson was bringing in soldiers to either jail or kill all Aboriginal people. Naturally, this caused unrest, especially because Robinson had expressly promised the people living on Swan Island that they would be safe there. Exasperated, he sent Tarenorerer away as quickly as she’d come so he could maintain order. She was forced to go with Parish while he searched for more Aboriginal women hiding in the Bass Strait Islands.

But Tarenorerer wasn’t done. When she returned to Swan Island at the end of December 1830, she riled up the population within just a few hours with repeated warnings that “the white people intended shooting them.” When confronted by Robinson, she told him that she “liked lutetawin, the white man, as much as a black snake.”

By some accounts, at this point, she was isolated to prevent her from inciting revolt. She was imprisoned on Gun Carriage Island, known today as Vansittart Island, where Robinson was moving the Tasmanian Aboriginal people living at his mission.

Influenza and other diseases ripped through these settlements quickly, and Tarenorerer was one of their many victims. Some people note her death as May 1831, others as June 5, 1831. She was probably buried in one of the graves on the island. Following what little we know about Aboriginal traditional burials, she should have either been cremated or buried in the soft sands on the beach, but probably did not receive this burial.

Robinson was “relieved” when Tarenorerer died. Though many members of various clans resisted colonial oppression, he came to blame her and her soldiers for “nearly all the mischief perpetrated.”

The death of Tarenorerer marked the beginning of the end of the Black War. Several small groups, all that was left of the original clans of the North and North East nations, surrendered to Robinson in stages. There were no more reports of violence between colonists and Aboriginal people in the settled areas of Tasmania after January 1832.

By 1835, Robinson reported that the entire Aboriginal population had been moved to various island missions and prisons that he had established. While the colonists had occasionally called for the military to “kill, destroy, and if possible, exterminate” every Aboriginal person in Tasmania, some of them did survive this war. As of 2016, more than 23,000 Tasmanians identified as Aboriginal, and Tasmanian Aboriginal culture is experiencing a resurgence.

All told, at least 1,000 lives were lost during the Black War: about 225 colonists and anywhere from 600 to 900 Tasmanian Aboriginal people. Tarenorerer was a forceful resistance fighter in a war her people ultimately lost. That so little about her is recorded is a stark reminder of how disposable the colonists saw Indigenous people in their quest for capital gain. As of 2023, discussions had begun to commission an Aboriginal artist to create a monument to the lives lost, but no memorial is currently standing.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook