The Mystery of Neolithic Slovakia’s Rotating Villages

It’s hard to think straight when your brain is asymmetric.

Over 5,000 years ago in what is today Slovakia, a Neolithic community erected a new building. It wasn’t the first “longhouse” in Vráble, an early town comprising about 100 buildings in all. But like those that came before it, the new construction sat a little leeward. So did the one after that. And the one after that. Over time, the entire village slowly turned counterclockwise—and the Stone Age inhabitants of Slovakia likely had no idea it was happening.

They weren’t alone. “We find [these longhouses] from the Paris Basin to Ukraine,” says Nils Müller-Scheeßel, an archaeologist at Kiel University and lead author of a recent paper, published last month in the journal PLOS One. “And what we find archaeologically is almost indistinguishably similar. They basically use the same building technique.”

These buildings were put up roughly once every 30 or 40 years, and each time the skew was counterclockwise—a pattern that occurred consistently over the course of 300 years.

Almost imperceptible today, and certainly invisible to the naked Neolithic eye, the curious rotation of the houses can be attributed to an esoteric glitch in the brain—a psychological process called pseudoneglect.

The sides of our brains have different responsibilities: The left hemisphere, for example, is in charge of producing speech, just as the right manages spatial attention. And those splits can sometimes manifest themselves in our interactions with the material world.

A portmanteau of “neglect,” pseudoneglect is a natural psychological phenomenon that causes individuals to pay more attention to the left side of their world. It has been observed in species other than humans, and in humans has been shown to affect senses other than sight, such as hearing. But it is most obviously apparent visually, and in the way that individuals will give weight to the left side of their field of view.

“It refers to a surplus of attention that is deployed into the left hemispace,” says Mark McCourt, a psychologist at North Dakota State University who is unaffiliated with the recent paper. “The commonly held idea is that it is a byproduct—an epiphenomenon—of the fact that the right hemisphere is specialized for the deployment of spatial attention.”

Twenty years ago, McCourt asked some test subjects to do a number of laboratory tests, all which split a line down the middle. (Some of the tests involved physical things like paper or a rod, others a cursor on a computer screen.) Few subjects split the line just so; most got it a little wrong, loitering on either side of the line’s true center. The majority of subjects erred to the left—a corroboration, McCourt says, of pseudoneglect’s imperceptible lefty bias in our brains.

Now, Müller-Scheeßel is arguing that the same process is responsible for the subtle rotation of Slovakia’s Neolithic towns. His hope is that his new research will prove the existence of the phenomenon on a larger, more manifest scale than McCourt’s experiment did.

In the Early Neolithic, much of Europe was dominated by the Linear Pottery Culture, so named for the population’s proclivity for making and using ceramics with linear designs, which litter the sites of their settlements across the continent.* These sites are also known for their longhouses, which have a particularly significant presence in southwestern Slovakia.

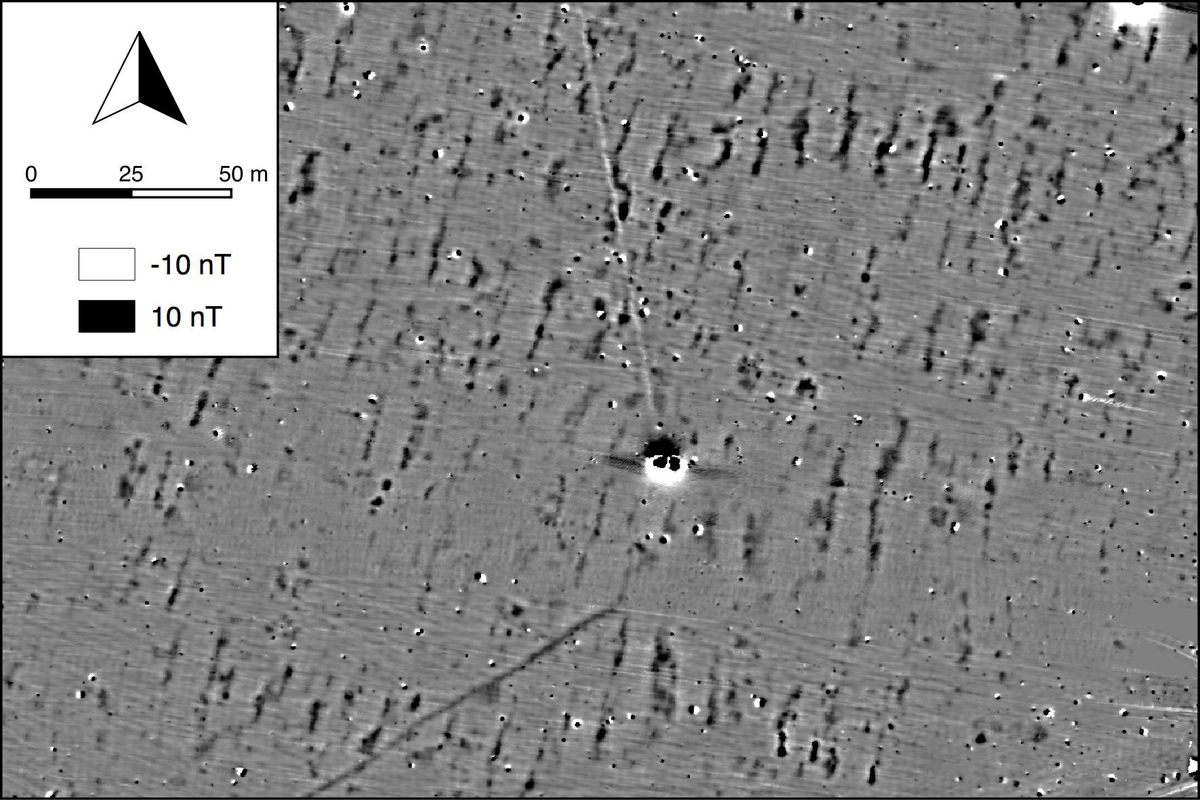

Though the buildings are long gone, Müller-Scheeßel’s team was able to use magnetic surveys to detect the parallel lines of timbers on which the houses were constructed. Despite the size of the settlements and the ample room the various communities had to work with, their urban planning—likely done by mere eyeballing—was pretty consistent.

“[They] could [have built] their houses in every direction,” Müller-Scheeßel says. “But there’s a certain tendency for alignment.”

Neolithic house rotation is evident in other sites across Europe, and a number of theories have been put forth about why the Linear Pottery Culture’s longhouses were oriented the way they were. Some argue that they were built at angles that would best withstand the wind. Others think that celestial bodies like the sun played a role. Still others suggest that longhouses were oriented toward each community’s ancestral homeland.

The matter is far from settled, but pseudoneglect could have played a role regardless of the primary reason for how the sites were laid out.

“It is very possible that the first house on [a] newly settled site was oriented according to the sun, and the others were aligned according to [that first house],” says Václav Vondrovský, an archaeologist at the University of South Bohemia in the Czech Republic who, last year, wrote a study proposing that the longhouses’ positioning was based on a solar alignment. “I don’t see the ‘sun theory’ and [the] ‘pseudoneglect effect’ [as being] in contradiction.”

What is certain, according to the recent magnetic surveys and earlier research, is that the Neolithic buildings at Vráble and elsewhere in Europe were built asymmetrically, and that their rotation was always counterclockwise. Müller-Scheeßel speculates that the advent of survey and construction tools would have put an end to those rotations. (Five-thousand years after the Vráble’s Neolithic heyday, the Greek dioptra and the Roman groma were used to measure right angles in construction, which hadn’t previously been possible.) Now, instruments like theodolites help surveyors get the angles they need with laser precision, and keep new buildings in line with older ones.

Pseudoneglect could also be connected to the environment of a given population. Recent research in Namibia showed that when rural populations moved to urban settings, they developed a greater left-leaning bias in their perception than they’d previously had.

Of course, those are modern populations. These are Neolithic ones. Which makes it a difficult thing to test. Studies of past groups force us to look at what they left behind. Without any ancient brains to study, it’s hard to say whether pseudoneglect operated the same way then as it does today.

“We can’t know how Neolithic brains differed from our own,” says McCourt. “It’s puzzling.”

There’s an old brainy joke about left-handed people being the only ones in their right minds. The rotating constructions of five millennia ago are a good way to remember that at the end of the day, we all bear left.

*Correction: This story previously stated that Corded Ware Culture sites were rotating. They were Linear Pottery Culture sites.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook