Skull-Shaped Beer Steins Were Once Popular Graduation Gifts

They were part of a broader wave of adventurous stein-craft.

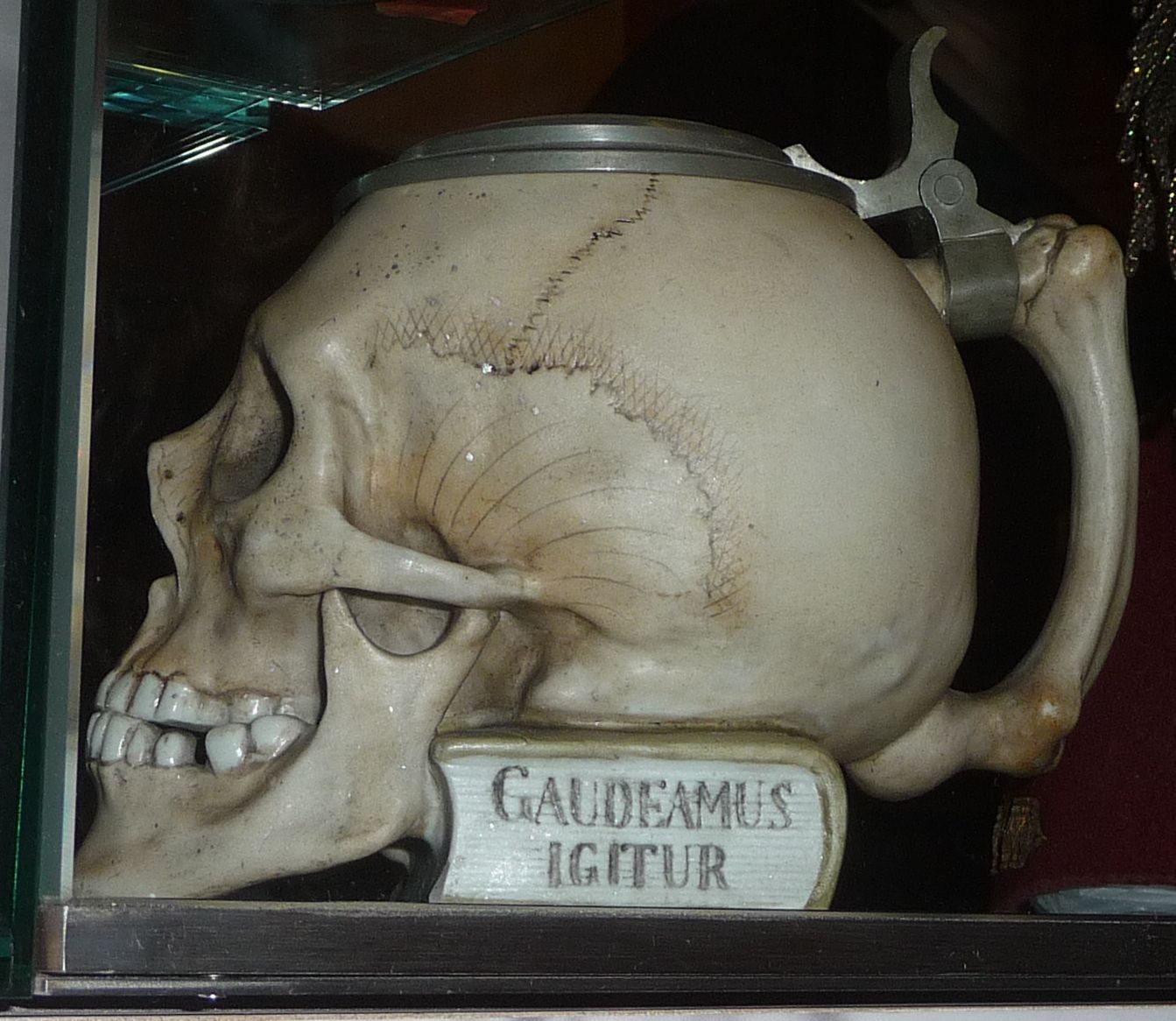

It’s the late 1800s in Germany, and you’re graduating with a medical degree. You’ve got your robes, your anatomical sketches and, of course, your trusty skull stein. You grab it by the bone-shaped handle and raise it for a toast, as you and your friends sing, “Gaudeamus igitur, juvenes dum sumus.” In other words: “Let us rejoice while we are young,” before our bones are buried in the earth.

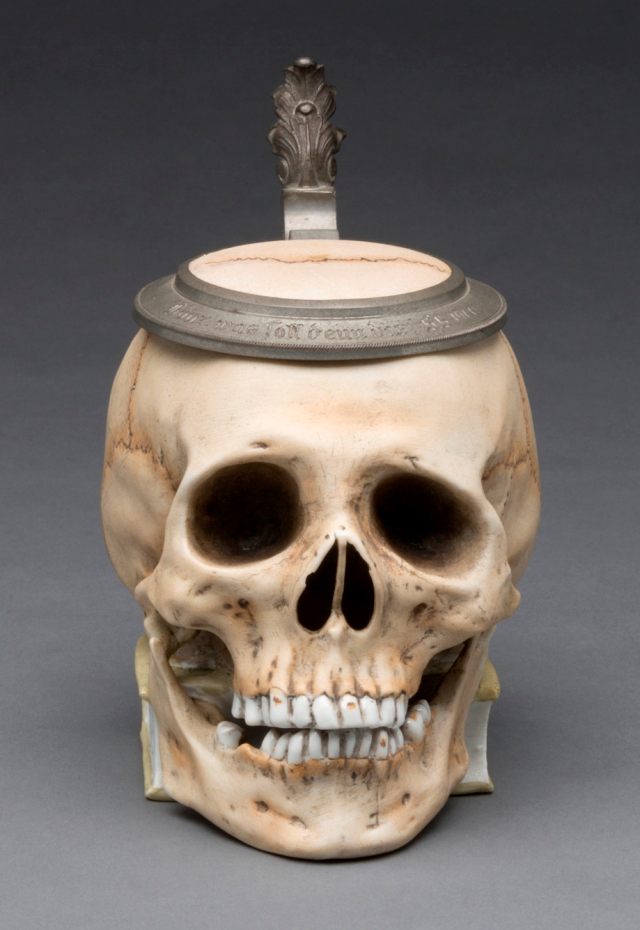

Yes, the skull stein—a hollowed-out model skull that could hold up to half a liter of beer in place of a brain—was all the rage in late-19th and early-20th century Germany, particularly in the central state of Thuringia. As beerstein.net explains, the skull stein’s precise origins are unknown, but it’s clear from their present ubiquity how popular they became. According to the site, they “seem to appear in almost every beer stein auction,” even as other kinds of steins from the same time and place are incredibly rare.

No manufacturer was so closely associated with the skull stein as E. Bohne Söhne, whose porcelain factory in the town of Rudolstadt churned our more than a dozen distinct versions of it. The best-known iteration, according to beerstein.net, was the so-called “skull on book,” which was pretty much exactly what it sounds like. The base of these steins, under the skull itself, is a Kommersbuch, a book that collects traditional student drinking songs such as “Gaudeamus Igitur,” whose opening lyrics are written on the book base. A particularly elaborate take on the “skull on book” stein embellished the book base with a music box, which would actually play the song. These features helped turn the skull stein into a popular graduation gift across different departments, even if medicine made the most immediate sense.

Other entries from the Bohne factory included a two-faced skull stein with a regular skull on one side and the devil’s face on the other, as well as another that replaced the bone handle with a pair of coiling snakes. This serpentine handle was an apparent nod to the “caduceus,” Hermes’ mythological snake-bearing staff, which was garnering significance as a medical symbol and could therefore appeal to medical students and doctors, the skull stein’s target demographic. While other porcelain manufacturers also tried their hand at skull steins, none cornered the market nor produced such striking varieties as Bohne. Some stoneware manufacturers in Germany’s Westerwald mountain range also produced skull steins, but in far fewer quantities and variations.

The Milwaukee Art Museum, which has a Bohne skull stein on display, situates the artifact within the broader phenomenon of “character steins,” which are hardly limited to themes of human anatomy. These steins were formed to look like singing pigs, elves, radishes, and even political figures such as Otto von Bismarck, to name but a few. The museum attributes this great boom in novelty to the technological advances of the Industrial Revolution, which gave manufacturers the tools to experiment more easily. And why not? These innovations in the craft remain appreciated to this day by amazingly prolific collectors—radishes, skulls, and all.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook