Zoology’s Favorite Hoax Was an Island Rat That Hopped on Its Nose

Harald Strümpke didn’t just create a lost archipelago, he created a sensation.

In the 1950s, tragedy struck the Pacific archipelago of Hy-yi-yi. It was once a tranquil place, populated only by little rodents with strangely specialized snouts, and the smattering of scientists who studied them. But an unfortunately timed spree of nuclear weapons testing by the U.S. military coincided with a conference that drew all the world’s experts on the rodent population to the islands. Soon the entire island chain was gone, and with it all of the snouty shrews as well as their dedicated researchers, including one Harald Stümpke.

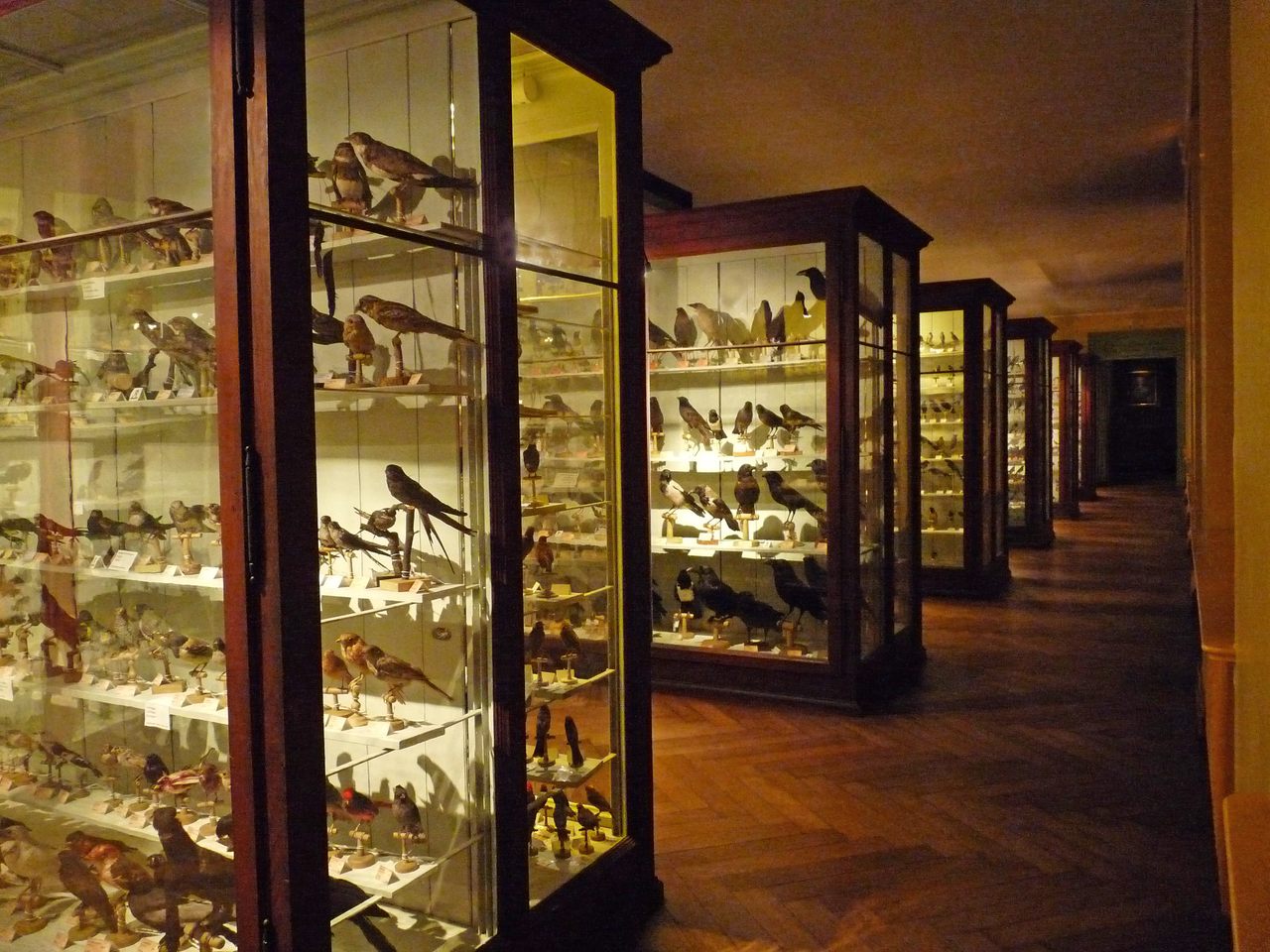

Fortunately for Stümpke, he never actually died because he never actually existed. Nor did the shrews nor the islands nor the blast that wiped them all out. But this fantastically elaborate hoax—including a meticulous aping of comparative anatomy papers of the day—captivated the scientific community and has become one of biology’s most infamous and beloved hoaxes. There’s even a taxidermied snouty shrew in the permanent collection of France’s rather reputable Strasbourg Zoological Museum and other natural history institutions.

Harald Stümpke was the pen name of a real German zoologist named Gerolf Steiner. Born in 1908, Steiner earned his doctorate at the University of Heidelberg in 1931 for research on the hearts of American cockroaches, writes Joe Cain, a science historian at University College London, in a 2019 paper published in the journal Endeavour. Steiner then hopped from teaching position to teaching position over a 40-something-year career with no notable focus or burst of discovery. At one point, he studied meat flies. At another, amphibians of central Europe.

One of Steiner’s most consistent interests was outside the realm of zoology. He loved to draw, and moonlighted as an illustrator during World War II. One day in 1945 when food was scarce, a student named Toni Stirtz offered him vegetables. To thank Stirtz, Steiner decided to draw a whimsical creature inspired by the German absurdist poet Christian Morgenstern, who once described a small animal that walks on its nose. Steiner was so pleased with his illustration that he decided to make another copy for himself. Rhinogradentia, the nose-rat, was born.

In 1946, Steiner began trotting his nose-rats, also called snouters, out in public. He spoke of them in classes and lectures, occasionally in the guise (and scraggly beard) of Stümpke, a favored alias.

Pretty soon, Steiner’s story evolved past the joke stage. The universe of the rhinogrades he had created was vast, intricate, and internally consistent, Cain writes. In other words, it had all the trappings of real science. There were notes on their comparative anatomy and Linnean hierarchy, embryological studies, phylogenetic speculations, anatomical drawings, and even fictitious monographs and journal articles that referenced an entire field of study surrounding them. “Together, it created an interlocking network of citations, tying back, eventually, to the fictitious biological station on the Hy-yi-yi,” Cain writes. “This was presented with an air of cold seriousness and professionalism.”

Stümpke (Steiner) wrote that a Swede named Einar Pettersson-Skämtkvist found the archipelago of Hy-yi-yi in 1941 when he wrecked on the island of Hy-dud-dye-fee (fleeing, of course, a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp). Stümpke noted that, rather tragically, Pettersson-Skämtkvist’s head-cold killed off all the approximately 700 indigenous people living on the island.

Once alone, Pettersson-Skämtkvist found a cornucopia of snouts among the island’s distinctive mammalian species. Stümpke described the 15 species of Rhinogradentia, and divided them into single- and multi-nosed groups, according to Bau und Leben der Rhinogradentia, the first publication of his work. Some bounced on curved noses like a pogo stick, and others walked upside-down on a set of four noses, their arms and legs nearly vestigial.

Snouters of particular note included the earwig, Otopteryx volitans, which used its nasal appendage as a rudder when it flew backward on the strength of its enormous ears, which flapped at a rate of 10 strokes per second. There was also the snuffling sniffler, Emunctator sorbens, which hunted by emitting long threads out of its nasal appendage that trapped tiny aquatic animals like flypaper.

Stümpke’s notes included scientific jargon so dense—“Now, anatomical investigations (here we follow Bromeante de Burlas’s discussions) have shown that in the polyrrhine species the nasal rudiment is cleft at an early embryonic stage, so that the rudimentary individual nostrils that develop from it have a holorrhinous differentiation, i.e. each forms a complete snout (cf. Fig. 1).”—that it was hard to even know where to begin to question it.

Stümpke’s manuscript on the rhinogrades first came out in 1961 and sold out quickly. The book’s first run offered no indication of its imaginary origins until the magazine Der Speigel called Steiner on his bluff in 1962. But zoologists and scientists of all sorts seemed to enjoy the gag so much that they were hell-bent on prolonging it.

In 1963, legendary paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson published a straight-faced review of the French translation of Stümpke’s work, Anatomie et Biologie des Rhinogrades, in the very serious publication Science (everyone was in on the joke). Simpson waxed poetic about Stümpke’s astonishing discovery and the lack of coverage it received, as well as the adaptations of the rodents themselves. “The ancestor of the rhinogrades was plainly a shrew, the only one ever to penetrate far out into the Pacific,” Simpson writes. “There it encountered not only open niches but also yawning cavities in the ecology, and its descendants filled them with uncontrolled exuberance almost as fast as you can say ‘Galápagos,’ or ‘Drepaniidae.’”

Simpson even included his own translation of the real Morgenstern poem that inspired the whole thing. As he clarified in a footnote: “As a matter of fact, this is a translation of the French translation and not of the original poem. A German translation of the English translation of the French translation of the German poem will be prepared in my laboratory as soon as we receive another grant.”

Steiner’s book continued to sell, and was further translated from German into Japanese, Italian, and English, the last of which successfully rebranded the rodents as “snouters,” the name they carry today. The snouters’ popularity offered Steiner a host of publishing opportunities in science education as examples of evolution and adaptive radiation—fantastical versions of Darwin’s finches. After the 1960s, Steiner never wrote another peer-reviewed zoological paper, having successfully pivoted more or less completely from science to education via prank maintenance. It’s hard to nail down whether Steiner initially imagined the creatures as a teaching tool, Cain writes, or if it was just a fortunate side effect of a joke.

Over the years, the hoax maintained a hold in the scientific community. Natural History, then the official magazine of the American Museum of Natural History in New York, published the entire first chapter of Stümpke’s work in their April 1967 edition without any hint of its origin. The New York Times followed suit with a snouter story on the front page on April 1, 1967.

Rhinogrades have also taken up residence in natural history museums, often without context among taxidermied specimens of real extinct animals. On April 1, 2012, the National Museum of Natural History in France held a two-month exhibit on Rhinogradentia, pegged to their claim of the new discovery of a snouter that eats wood by using a nose that rotates like a drill. Fake taxidermied rhinogrades also nosed their ways into an exhibit at the Museum of Ethnography in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and the permanent collection of the Haus der Natur museum in Salzburg, Austria.

The legacy of Stümpke—and, to a lesser extent, Steiner—even ripples out into the real world. Three species of actual animals bear the zoologist’s name and pseudonym, including a snout mouth and two shrew rats. One of the shrew rats, Hyorhinomys stuempkei, lives only on Mount Dako on Sulawesi in Indonesia, according to Mongabay. It also has a nose that resembles a hog’s, extremely long teeth, and strangely extended pubic hairs. The rat is so unusual it was given its own genus, and might make us question whether we’ve been had again—though the discovery was announced in June 2015, not April 1.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook