Red Velvet Cake’s Journey to The Juneteenth Table

Make the dessert that first inspired the popular crimson slice.

Iconic recipes have to come from somewhere. Welcome to First Draft Foods, where this week we delve into the legends and controversies behind the world’s favorite dishes.

With its deep crimson layers topped with thick tufts of snowy frosting, red velvet cake cuts a striking figure. This unmistakable cake ranks high in the pantheon of iconic American desserts.

“If you show up with a red velvet cake, people will love you,” says Vallery Lomas, the winner of The Great American Baking Show and the author of Life Is What You Bake It: Recipes, Stories, and Inspiration to Bake Your Way to the Top. “I don’t think there’s anything you could bring to a barbecue or a cookout that will make people more excited.”

Whether sold in mile-high slabs or diminutive cupcakes, red velvet is often more recognized for its dramatic aesthetic than its flavor. In essence, it’s a mild, moist-crumbed chocolate cake. Without the addition of the better part of a bottle of red dye 40, it would appear pale brown—and fail to inspire the appropriate Pavlovian response.

“We eat with our eyes, and there’s that expectation of seeing something and expecting a certain taste,” Lomas explains. “Historically, it’s been made with a number of things, but in the South these days, it’s made with red food coloring, which gives it that quintessential brick-colored look.” In her recipe, she opts for a buttermilk cake base, fortified by a splash of vinegar and leavened with baking soda for the right texture. In her opinion, it doesn’t feel right without its vibrant coloring.

For many Black chefs and bakers, red velvet cake’s distinctive color has earned it a place of honor at Juneteenth celebration tables. “Red for Black people, red for anyone, is a powerful freaking color,” says Nicole Taylor, author of Watermelon and Red Birds. “When I put on red lipstick, I feel royal, I feel regal. For Black folks, red is symbolic of sacrifice, bloodshed. It is a color in the Black liberation flag. You see red repeated a lot in Black culture, in Black spirituality, in Black food. I do think that’s one of the reasons why red velvet cake is now a food that people now associate with the Juneteenth holiday.”

Yet, as Taylor points out, there’s no evidence that red velvet cake appeared on the first Juneteenth in 1865. “In work by scholars and food writers, you see that newspapers talked about what the formerly enslaved folks ate,” Taylor says. “You don’t see red velvet cake.”

When more than 200,000 Black Texans discovered that legally they should have been free since the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation two years prior, they celebrated with barbecues. While the color red may have appeared in the form of lemonade tinted with mashed strawberries, the dye that gives red velvet its shocking hue would not be invented for decades.

“For a long time, the traditional Juneteenth dessert was a slice of nice, ripe, cold watermelon,” says Adrian Miller, the James Beard award-winning author of Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. “As Juneteenth becomes more notable, people start thinking of more red-colored foods to add. So you start seeing red velvet cake and strawberry pie on the menu.”

Recipes for velvet cakes, so named for their luxurious texture, first appeared in the late 1800s. The name was nod to the use of softer wheat or cornstarch used to cut down the gluten, thereby producing a softer mouthfeel. In BraveTart: Iconic American Desserts, Stella Parks cites cookbook author Alvin Wood Chase’s “Velvet Cake” recipe in 1873 as the first example of such a dessert. She also notes that in 1911, a “Velvet Cocoa Cake”—essentially a modified devil’s food cake—appeared in a newspaper in Ohio.

The red color, though, was a happy accident. “The leavening agents around the turn of the 20th century interacted with cocoa in a way that imparted a reddish hue,” Miller says. “I was looking at early Black cookbooks and I just didn’t see the name red velvet cake, but I saw the name red devil’s food cake and looking at the process, it was the same as red velvet.”

During this period, home bakers would have been using natural-process cocoa powder, which at the time was higher in anthocyanin. When the acidic cocoa powder (and sometimes buttermilk or vinegar) reacted with the neutral baking soda, it brought out a distinctive mahogany pigmentation. Dutch-process cocoa powder, which is neutralized by soaking the cacao beans in an alkaline solution of potassium carbonate, can’t produce the same reaction. “So people started adding food coloring to create that look,” Miller explains.

Enter Adams Extract and Spice. Founded in 1888 in Battle Creek, Michigan, the company first sold a green sarsaparilla extract before branching out to vanilla and other flavors. John A. Adams, the founder, began selling his extracts door to door. In 1947, his grandson, John G. Adams, released a four-pack of food dyes. To promote the new products, his wife, Betty, had an idea.

“To promote that four-pack, the company printed his wife’s recipe for red velvet cake,” says Carrie Lumb-Dewey, a representative for Adams Extracts. “She added in the red food coloring to accentuate the red color that was already in the cake.”

It wasn’t long before ruby-hued red velvet cakes with white icing were making their way around the country, including in the 1943 edition of The Joy of Cooking. In the 1948 cookbook A Date with a Dish: A Cook Book of American Negro Recipes, Freda DeKnight, the first food editor of Ebony magazine, published chocolate devil’s food cake recipe accentuated by a few drops of red food coloring. But it wasn’t until 1951, writes Parks in BraveTart, that a Texas newspaper first mentioned the name “red velvet cake.”

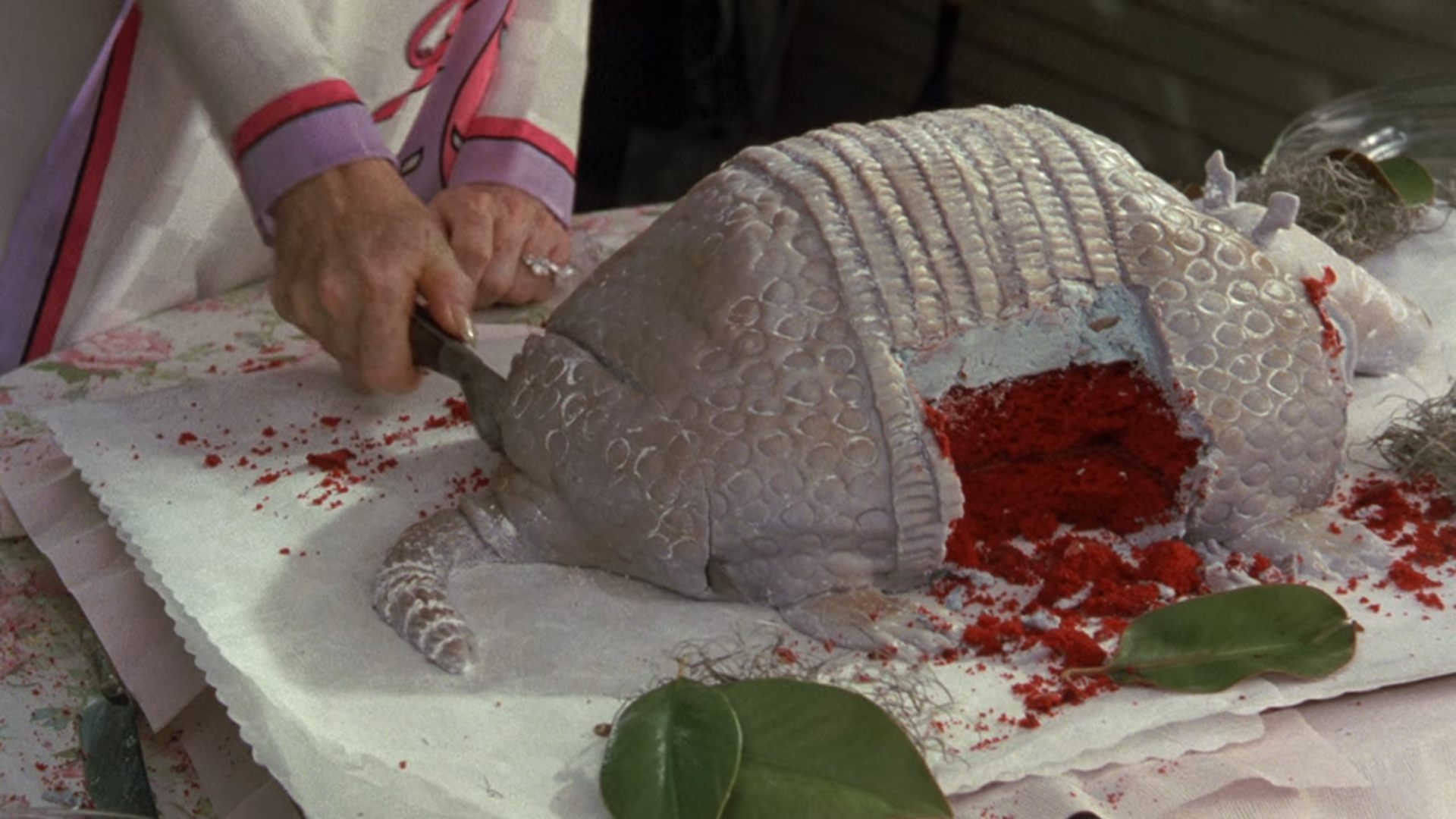

The cake continue to evolve, picking up its now-signature cream cheese frosting in the 1970s. Several crucial pop culture cameos permanently put it into the limelight. The 1989 movie Steel Magnolias featured a red velvet groom’s cake shaped gruesomely like a realistic armadillo, while in the third season of Sex & the City, Carrie (Sarah Jessica Parker) and Miranda (Cynthia Nixon) dish about men while devouring cupcakes from Magnolia Bakery.

“Sex & the City changed the culture of cake from something kids ate at a birthday party to something these sexually vivacious women valued on par with shoes and bags. You would eat a piece of red velvet cake at Barney’s,” says David Sax, author of The Tastemakers: Why We’re Crazy for Cupcakes But Fed Up With Fondue. “It transformed cupcakes and other associated pastry treats into these edible bits of consumer culture.”

The cupcake craze of the early aughts coincided with the rise of food blogs, which quickly latched onto red velvet’s new association with luxury. Like the other brand-name items fetishized by the show, cupcakes became aspirational—and were a lot more accessible to the general public than a $600 pair of Manolo Blahniks. And while the characters aren’t even eating red velvet cupcakes in Sex and the City, it quickly became one of Magnolia Bakery’s most popular flavors.

It might have all come down to the name. “It wasn’t a chocolate cake; it wasn’t a vanilla cake; it was red velvet. It was luxurious. It was sexy,” Sax says. “So red velvet cake started with grandma’s cooking, but at the other end of the spectrum, it was the hot new cake of 2008.”

In response to a growing distaste for Red 40 and other artificial colors, some bakers have experimented with adding beets or red wine for a cake with a more subtle shade of red. Plus, naturally derived red food dyes are increasingly available on the market. Even Adams Extract uses beets as the base for their current formula.

Still, for a cake that honors the confection’s historical roots, there’s no need for red food coloring. The recipe below, based on an early 20th century recipe for “red chocolate cake,” makes an extremely simple loaf with a subtle crimson hue.

But there’s no need to go full retro. While it wouldn’t have been traditional on a red devil’s cake in the early 20th century, Lomas strongly advises against skipping the cream cheese frosting. “For me, it’s not really red velvet if it doesn’t have cream cheese frosting,” she says. “I don’t really see the point otherwise. If you see a vanilla buttercream, it’s a missed opportunity.”

Velvet Cocoa Cake

- Prep time: 15 minutes

- Cook time: 40 minutes

- Total time: 55 minutes

- Makes one loaf cake

Ingredients

- 1 cup flour

- ¾ cup sugar

- ½ cup natural chocolate powder (not Dutch process)

- 1 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- ¾ teaspoon salt

- ½ cup neutral oil, such as canola

- One egg

- 1 cup sour milk (or milk with a tablespoon of lemon juice)

Instructions

-

Preheat oven to 350°F, and lightly grease a loaf pan.

-

Mix together sugar, oil, and chocolate powder until smooth. Then, add the egg and incorporate completely.

-

In another bowl, mix together flour, salt, baking powder, and baking soda.

-

Alternate adding the sour milk and the wet ingredients to the flour mix, and stop stirring once the mixture is completely combined. Pour into the prepared pan.

- Bake for 40 minutes, or until a toothpick inserted comes out clean. Frost as desired.

Notes and Tips

This humble loaf, adapted from an early variation of the red velvet cake, is not going to be truly red, more of a dark reddish brown.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook