Meet Baked Alaska’s Prototype, ‘Alaska, Florida’

This parlor trick of a dessert has a long, complicated lineage.

Iconic recipes have to come from somewhere. Welcome to First Draft Foods, a week where we delve into the legends and controversies behind the world’s favorite dishes. Previously, we learned about the origins of red velvet cake, chowder, and Caesar salad.

On January 1, 1880, the British journalist George Augustus Sala was dining at Delmonico’s, one of the swankiest tables in New York City. That night, he encountered something extraordinary. At the culmination of the meal, the kitchen presented him with a gastronomic magic trick: a dome of ice cream shrouded in meringue, then, in defiance of all logic, burnished to a golden brown under the heat of a red-hot metal salamander.

“They served us, on New-Year’s Day 1880, with a baked ice, appropriately styled an ‘Alaska,’” Sala marveled later in Living London: Being Echoes Re-Echoed. “It was strangely good. The soufflé was quite hot and the ice was quite cold; and we were not, immediately afterwards, taken to the Bellevue Hospital to be treated for indigestion.”

Baked Alaska is one of those desserts that food writers have called retro for half a century. The fundamentals—ice cream and pastry beneath meringue—haven’t changed much since Sala sampled it in 1880, except for the show-stopping tradition of using high-proof alcohol to set the dessert on fire before serving. It’s the gastronomic equivalent of a magic trick, a snowy mountain licked by flame. Chef Gabrielle Hamilton once called it “simple ice-cream cake, but with the tension of a good novel … and the beauty of a poem.”

According to popular mythology, Charles Ranhofer invented the dish at Delmonico’s in 1867 and named it in honor of the Alaska Purchase. While the French pastry chef certainly deserves credit for popularizing this contradictory confection, the reality is that its roots are older and more convoluted.

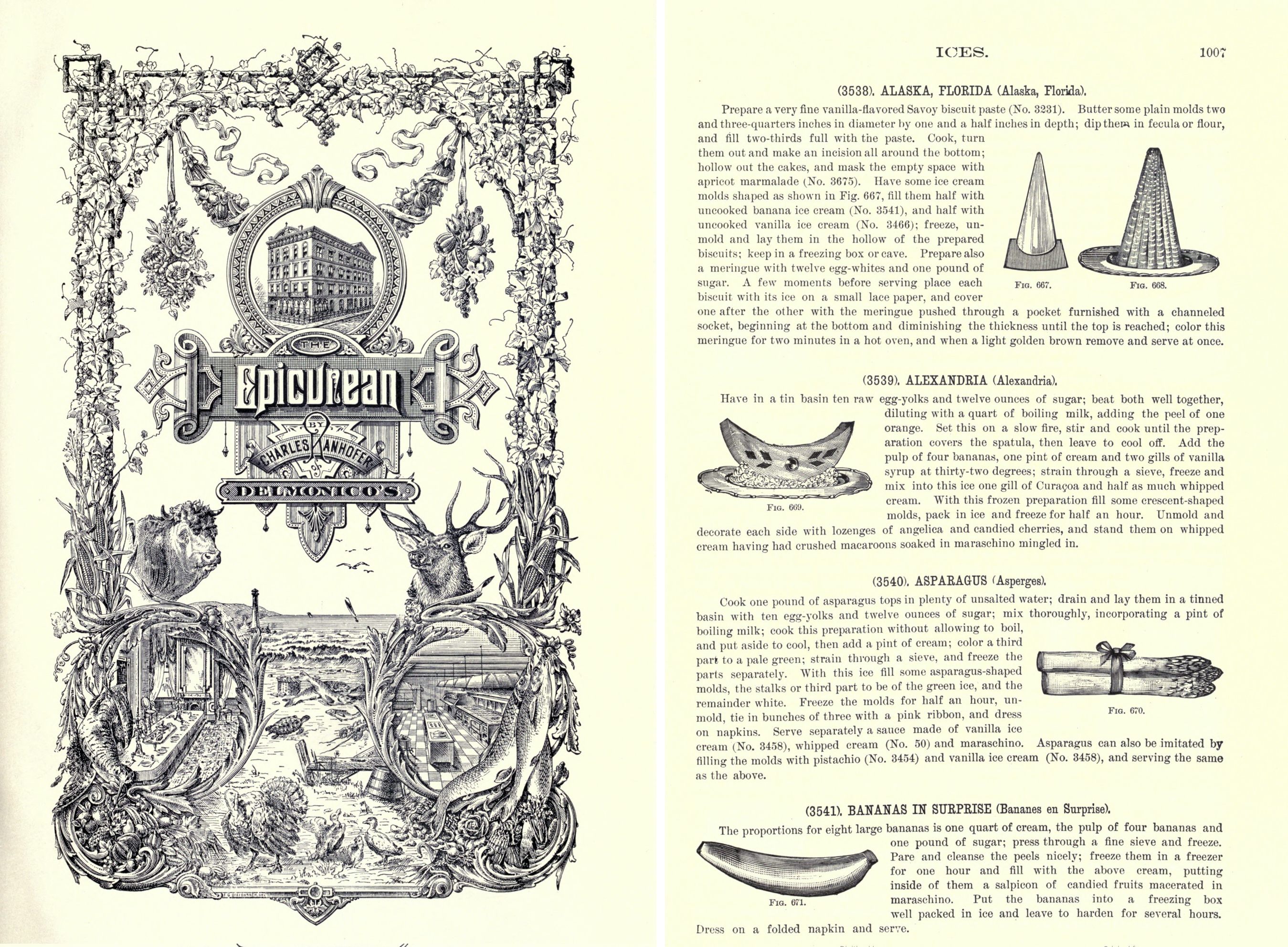

“Ranhofer himself never called it a baked Alaska,” says food historian Jim Chevallier. It’s true that Ranhofer published a recipe for a similar dessert in 1894 in the cookbook The Epicurean, under the name “Alaska, Florida.” But the name has nothing to do with either state, other than in regards to their climate. “He’s just saying it’s ‘Alaska’ because it’s cold and ‘Florida’ because it’s hot,” explains Chevallier.

Ranhofer’s version of the dessert included a slick of apricot marmalade on its biscuit base, as well as equal parts banana and vanilla ice cream. No flames were mentioned in his recipe, but by the time Ranhofer published his cookbook in 1894, chefs had been setting food on fire for centuries.

“Cooks have always liked to do trickery,” Chevallier says. And when it comes to impressing guests, few flourishes do the job quite like live fire. For a particularly show-stopping centerpiece, 15th-century cooks figured out how to transform a dead peacock into a feathered, fire-breathing dragon.

“Get an apparatus of iron driven into a large cutting board and shove this iron through its feet and legs so it cannot be seen; in this way the peacock will be standing so that it will seem to be alive,” instructs one recipe from an anonymous 15th-century cook in The Neopolitan Recipe Collection. “Get a little camphor with a little fine cottonwool around it and put this into the peacock’s beak and soak it with a little aquavita … when you want to serve it, set fire to the cotton-wool: in this way it will breathe fire for a long time.”

Chevallier also points to a 15th-century recipe from the cookbook Le Viandier for fried butter, which uses a starchy coating to keep the dairy from melting under extraordinary heat. But European cooks weren’t the only ones playing with fire. “In the 1840s, there are accounts of various travelers going to Peking, and one says that one of the favorite dishes there is ‘roasted ice,’” Chevallier says. “After being enveloped in spices and paste—which means dough—boiling pork fat is poured over it. The grand idea is to serve ice before it has time to melt.”

One reference to this dessert comes from the German Romantic poet Heinrich Heiner, who wrote in 1843 of the “roasted ice which the Chinese prepare so artistically by holding a lump of something frozen, wrapped in a thin coat of dough, for a minute over the fire.”

In 1859, The Atlantic published a short story entitled “Mien Yuan,” which mentioned something called “Baked ice à la Ching-ki-pin.” The author described the dish floridly: “The ice was enveloped in a crust of fine pastry, and introduced into the oven; the paste being baked before the ice—thus protected from the heat—had melted, the astonished visitors had the satisfaction of biting through a burning crust, and instantly cooling their palates with the grateful contents.”

While this description is still a long way from baked Alaska, the technique made an impression on chefs abroad. “There’s pretty clear evidence that the Chinese method was introduced to France,” Chevallier says. French food journalist Baron Brisse wrote in 1866 about how visiting Chinese chefs at the Grand Hotel in Paris delighted their French counterparts by showing them the method. “The dessert cook at the Chinese Mission was taught how to make vanilla and ginger ice,” says Chevallier. “He describes that you wrap each ice in pastry and put it in the oven.”

French chefs took to the idea quickly. Recipes for omelette surprise—a “surprise omelet” consisting of an ice cream bombe covered with whipped egg whites and brûléed—started cropping up in the 19th century. Some chefs refer to the dish as omelette norvégienne, omelette Norwegge, or omelette sibérienne, presumably because Norway and Siberia were as frigid and exotic to the French as Alaska would have seemed to New Yorkers.

In 1876, the American suffragette Mary Foote Henderson was crossing the Atlantic on a German steamer when she encountered another dead-ringer for baked Alaska. She describes the dish of meringue-swaddled ice cream browned under a “red-hot salamander” in her 1889 book Practical Cooking and Dinner Giving. “The gentleman who told me about this dish insisted that it was put into the oven and quickly colored, as the egg surrounding the cream was a sufficiently good non-conductor of heat to protect the ice for one or two minutes,” wrote Henderson.

Curiously, Henderson also wrote about dining at Delmonico’s, yet makes no reference to Ranhofer’s Alaska, Florida. It’s possible she simply ordered something else, but seems more likely that Ranhofer hadn’t gotten around to putting his version on the menu yet.

Just two years after his recipe for “Alaska, Florida” debuted, Fannie Farmer seemingly decided to ditch Florida altogether. She featured a recipe for “Baked Alaska” in 1896’s The Boston Cooking-School Book that looks more or less like the dish served today.

“That’s kind of the picture: the idea of baked Alaska itself used to be a distortion of Ranhofer’s Alaska, Florida,” Chevallier says. “The concept of baking ice cream in pastry seems to come to Europe from China. And there are a lot of similar ideas, the Medieval idea and a recipe made at Thomas Jefferson’s in 1802.”

Parsing out who deserves credit for culinary inventions can be a sticky business. Perhaps, instead of attributing baked Alaska to a single genius, it’s better to think of its existence as the result of a grand collaboration, across continents and time.

Alaska, Florida

Adapted from "The Epicurean" by Charles Ranhofer

- Makes four large servings

Ingredients

- 4 cups banana ice cream, either homemade or store bought

- One package of ladyfingers (at least 12)

- ¼ cup of apricot jam

- Three egg whites

- ½ cup sugar

Instructions

-

Line a one-cup measuring cup or teacup with plastic wrap, and a baking sheet with a silicone sheet or lightly-greased parchment paper.

-

Spoon banana ice cream into the cup, and gently flatten, making sure no bubbles remain. Use the plastic wrap to tug out the ice cream onto the baking sheet, and repeat three more times.

-

Split ladyfingers along their seam. Working piece by piece, spread the flat halves with the jam. Press the jam-spread sides against the ice cream, one at a time, creating a rounded dome. Feel free to squish and mold the ladyfingers into place, covering as much of the ice cream as possible. Depending on the size of the ladyfingers, you may have a few left over, but account for four to five ladyfinger halves for each serving.

-

Put ice cream domes into the freezer, and allow them to freeze hard, for at least three hours.

-

Before serving, put egg whites in a bowl and with an electric mixer, beat them until stiff peaks form. Gradually add in the sugar, and beat until it’s completely incorporated.

-

With a rubber spatula, scrape the meringue into a large Ziploc bag, and press the mixture into one corner, massaging out the bubbles. Snip the end of the bag.

-

Remove ice cream from the freezer. Starting at the bottom rim of each dome, pipe large dots of meringue in a circle. Then, move up and pipe another round above the first. Gradually decrease the size of the dots up to the top of the dome, covering the ladyfingers completely.

-

Repeat with the rest of the ice cream domes. Then, turn your broiler on high, and slide the cookie sheet in the oven.

- Watch the Alaska, Floridas carefully. After two minutes, the meringue should be a rich brown. Remove from the oven, and with a thin spatula, move the desserts to individual plates. Serve immediately.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook