A Self-Taught Indian Artist Sculpts Intricate Birds From Paper and Wire

Around 100 bird species have taken wing from the studio of New Delhi artist and conservationist Niharika Rajput.

In her modest studio in New Delhi, Niharika Rajput transforms simple materials like wire, epoxy, and paper into incredibly detailed sculptures that are exhibited or commissioned by wildlife organizations and art galleries around the world. Over the past five years, the Indian wildlife artist has built around a hundred species. In her creations, a hummingbird hovering in the air laps up nectar from a coneflower. Newborn bulbul chicks beg their mother for food. A male kingfisher offers fish to a female kingfisher, perched on a mossy piece of driftwood.

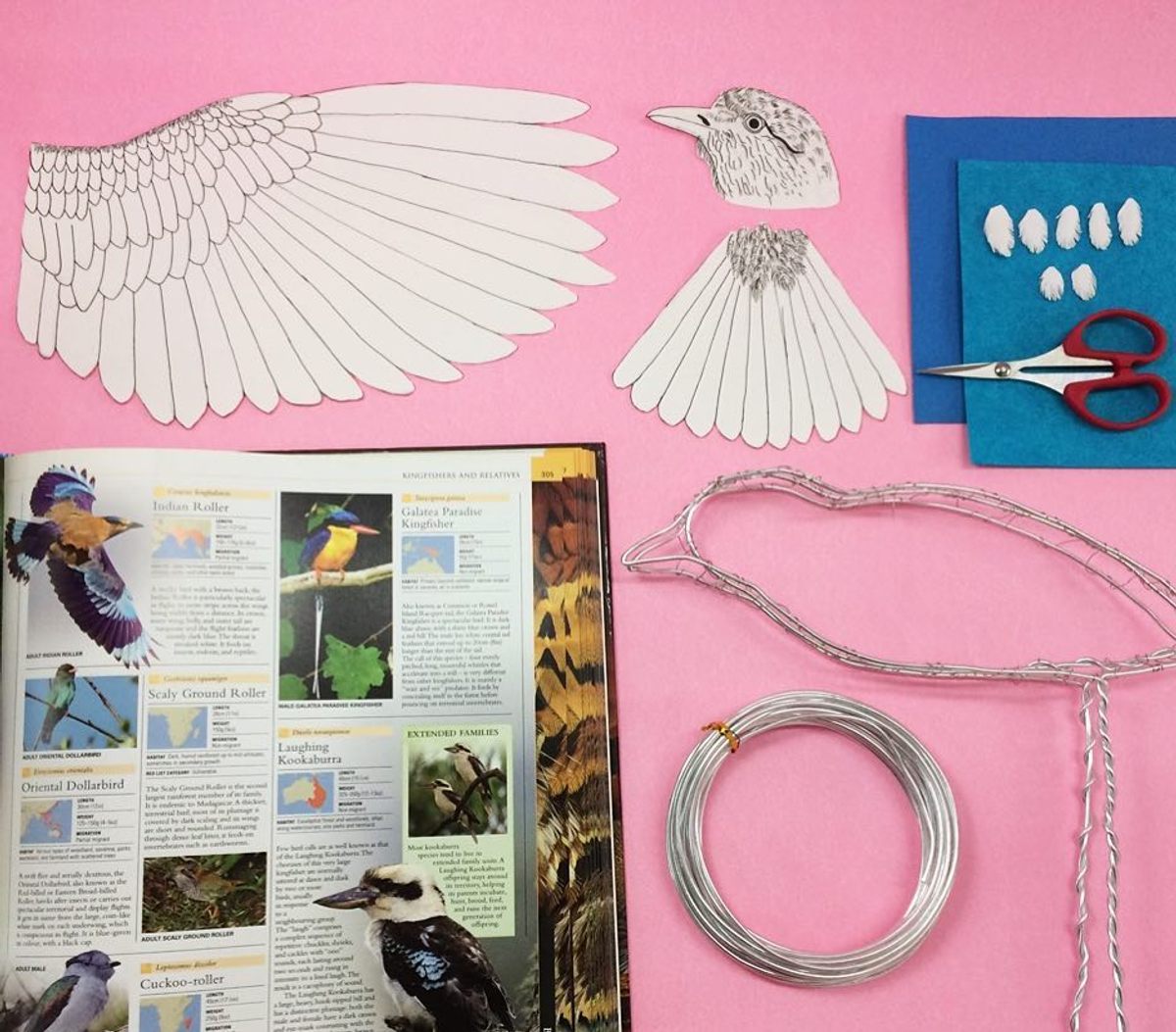

Rajput crafts both miniature and life-size models of birds. The miniatures usually come in the form of bird figurines mounted on a block, or hanging mobiles with wings outstretched in flight. For these, she uses epoxy to shape the bird’s body, paper cut-outs for the wings and tail, and wire for the legs and feet, all of which she coats with acrylic paint. These can take a few days to make.

The life-size sculptures, on the other hand, take weeks and even months to execute. Rajput starts by making an outline of the bird’s body from wire, stuffing the hollow with newspaper, and covering it in strips of paper for an even surface. Then she works on the talons, eyes, and beak with epoxy. Finally, in her most elaborate step, she cuts thousands of body, wing and tail feathers from pastel paper and glues them individually—a technique that demands precision, and has taken the artist years to perfect.

On Instagram, Rajput has earned 11,000 followers under her brand name, Paper Chirrups. She often speaks at bird festivals and schools, where she teaches children about birds in peril through the medium of art. The artist spoke with Atlas Obscura about her artistic process and sources of inspiration.

What’s a day in your life like?

When I wake up, I go for a walk. That is when I spot birds. Sometimes I carry my binoculars with me, sometimes my spectacles work just fine. After that, I sit down to work. I put on a documentary on birds. While it plays, I do my work. Every day there is a different step of the process that I am working on, but some of the steps are quite repetitive, like cutting the same feathers again and again.

When did you start making nature-inspired art?

When I was in college, I joined [the craft boutique] People Tree in New Delhi as an intern. I used to sketch and build a lot of 3D stuff with all kinds of materials—bamboo, rope, etc. That is where I got introduced to building very basic models of birds with epoxy. But I wanted to experiment and make it more realistic. Later, in 2015, when I saw a flock of red-billed blue magpies take off from a pine tree in Himachal Pradesh, I started building birds. I experimented with different materials and landed on the process that I follow now.

What was your first bird sculpture?

I built hen harriers for my 2016 campaign with Birders Against Wildlife Crime in the U.K. These were the first sculptures of the kind I make now. Before that, when I was experimenting, I made some other birds, such as the greater bird-of-paradise, superb bird-of-paradise, purple sunbird, splendid fairy-wren, and tufted coquette (a hummingbird).

When I was working on the birds-of-paradise, the body was made out of regular epoxy, but instead of using paper for the feathers, I used thread. I was trying to get that texture of the feathers, but it didn’t come out very well. The real look of the feathers came out in the hen harrier.

What’s been your most challenging, longest-running project?

The kingfisher sculpture took me three months. It was a personal project I had chosen for a wildlife art competition in London.

It was challenging because that piece is a narrative, showing an interaction between two birds, and it involves a perch for the bird. I had also built a fish in the beak of the bird—that was my first time making a fish. The kingfisher postures were very difficult, especially the one on the wood with its wings half-open, half-closed. It took a long time, and I did it very peacefully because I didn’t want to go wrong with it.

In terms of species, which has been the most challenging?

Owls are very challenging. Not because of their feathers or the painting part, but because of the shape of their head. It’s very different from the rest of the birds, and the beak is almost in the face.

How do you choose your subjects?

I don’t have a big studio, so at the moment I cannot build large birds. So I look at smaller species like hummingbirds, or build miniatures. That is one way. Another is when I am commissioned by an organization. For personal projects, I choose birds that have vibrant colors. I am a fan of passerine birds.

What role do you think artists play in wildlife conservation?

When I do my workshops with children in Ladakh and ask them about the types of animals found there, children give me answers like “elephants, tigers, and lions.” There are no elephants, tigers, and lions in Ladakh. That means they don’t know—we need to educate them. If the basics are not clear, how do you expect them to help in conserving species that are going extinct?

Any upcoming projects you are excited about?

I will probably be doing an exhibition on hummingbirds soon. I want to finish my series and make as many hummingbirds as possible. After the kingfisher, my piece on a hummingbird sipping nectar from a flower was very challenging and I want to do more.

I think I am set for life. I have enough projects planned in my head. I want to cover birds from different regions of the Indian subcontinent. The ultimate aim is to cover all species of birds in the world, but I don’t think that’s going to be possible. People sometimes ask me, “Why don’t you work on other animals? Why birds?” I may try my hand on other wildlife, but I can’t move on from birds, because I can never be done.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook