Oscar Dunn, America’s Forgotten First Black Lieutenant Governor

The New Orleans pioneer’s legacy has been overshadowed, and an intended monument never built.

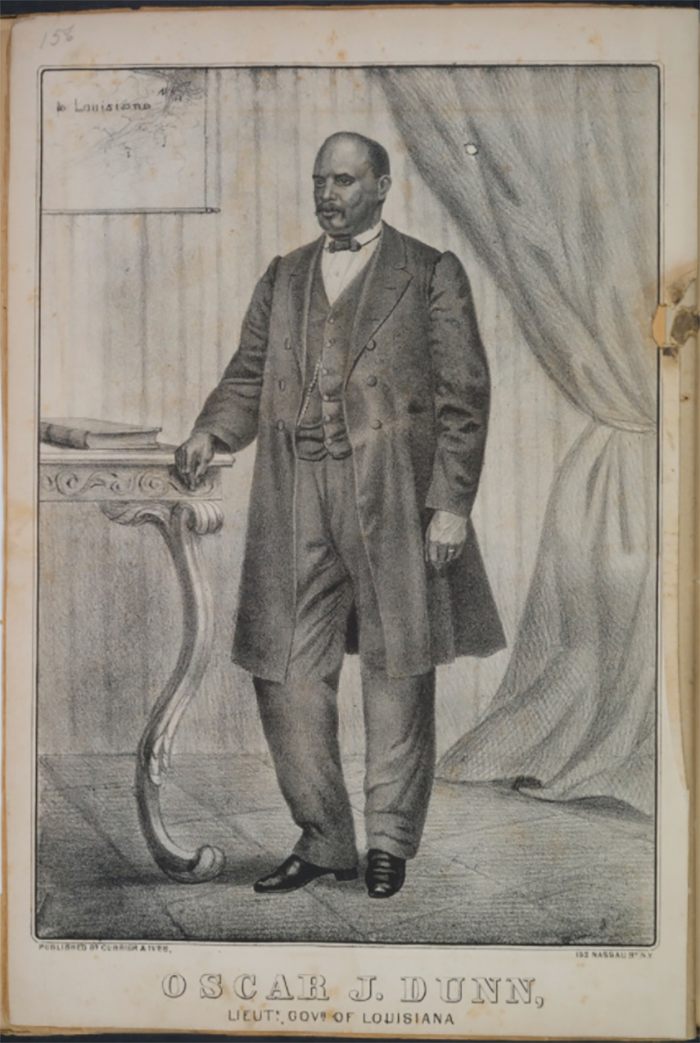

There are statues of many people in the city of New Orleans. But Oscar James Dunn isn’t one of them, despite having made his mark as the nation’s first African-American lieutenant governor who served in Louisiana from 1865-1871.

New Orleans native Brian K. Mitchell remembers his great-grandmother lauding his distant relative’s accomplishments, but when he got to school, he discovered no one else had ever heard of his great-great-great uncle Oscar Dunn.

After Dunn’s death in 1871, $10,000 was appropriated by Louisiana State Legislature Act 57 to erect a monument in Dunn’s honor. However, it was never used. By Mitchell’s account, the monument should have been grand, given the vast amount of money given to the project. But it didn’t happen, and there’s no record as to why. “I’ve never come across a document that clearly states why the monument wasn’t constructed,” Mitchell says.

A significant political figure in Reconstructionist Louisiana, Dunn rose to prominence after the Civil War, ultimately becoming the first black lieutenant governor of the United States. But after his untimely death in 1871, Dunn faded into obscurity. Today, there are no monuments, no statues, no major streets named for him in New Orleans.

“There was a purposeful rewriting of history after Reconstruction,” says Mitchell, an assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas Little Rock. “Whites believed blacks couldn’t function without them, so exceptions were made in the historical record.”

To remove the shroud of mystery surrounding his ancestor, Mitchell wrote his dissertation on Dunn. He gleaned much of the information from the personal correspondence of Dunn’s long-time friends John Parsons and J. Henri Burch, as well as press clippings and other official documents.

Dunn was born a slave in 1822 in New Orleans. In 1831, his mother married a free man of color named James Dunn who bought her freedom, and that of Dunn and his sister, for $800. Dunn assumed his stepfather’s surname and received a traditional English education, Mitchell wrote, which likely meant he attended the Grimble Bell School, an institution that educated free black people in Louisiana. He also apprenticed as a plasterer, becoming extremely skilled at the craft. That work led him to leadership positions in Louisiana’s black masonic lodges, which, according to Mitchell, were extremely influential in Reconstructionist politics in the South.

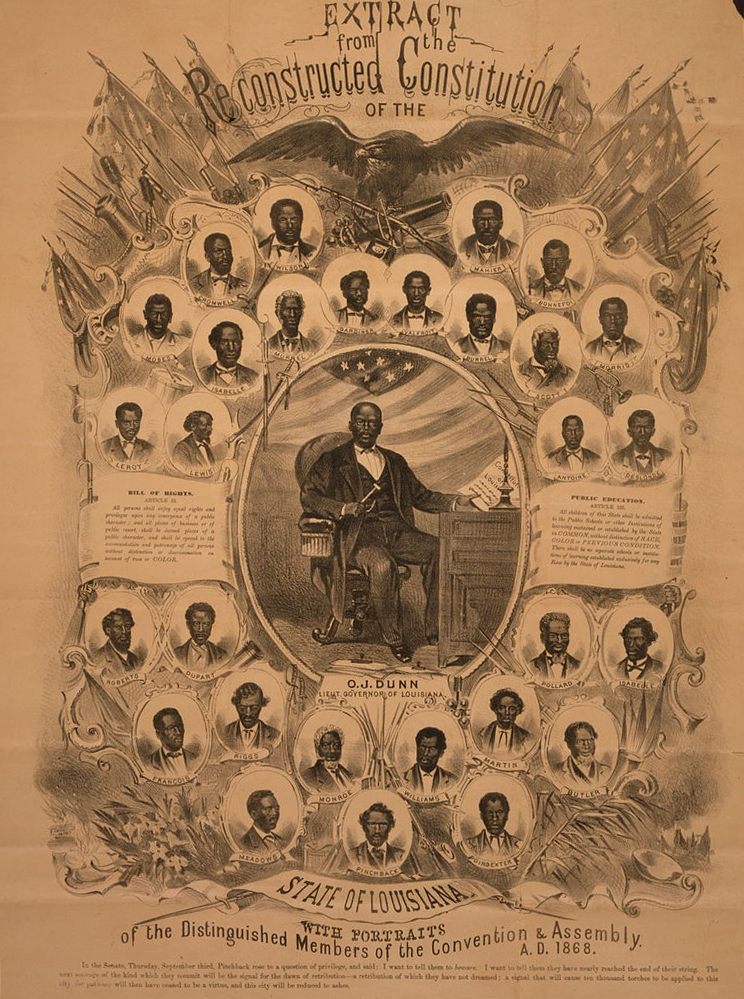

After the Civil War, black people did gain some rights in Louisiana’s 1864 Constitution, which was passed so the state could rejoin the union. The new Constitution gave African Americans freedom from bondage, the right to acquire and own property, make contracts and testify in court. Those specific parameters were put in place largely to prolong the plantation economy. Plantation owners often offered poor wages to former slaves so they would continue providing labor.

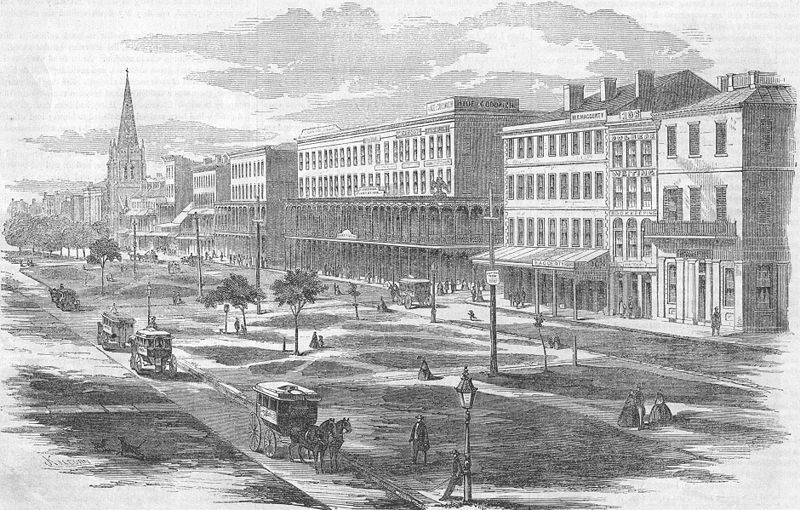

Dunn set about to protect freed men by securing fair wages. While he never sat for the bar exam, Dunn was a scholar of the law. According to a biography written by his friend John Parsons and published in an 1871 issue of the Weekly National Republican, “his habits of study had given him an ample amount of legal learning.” That legal knowledge was the impetus behind his contracts office that operated on Canal Street in New Orleans. Contracts were used to ensure newly emancipated slaves were fairly compensated for the labor they provided on plantations.

During this time, Dunn also dipped his toe into the political arena. He was appointed to the city council of New Orleans and led efforts to push for universal suffrage for black men. While the 1864 Constitution did offer some rights to freed men, the right to vote was not one of them. That right came in 1870, after years of campaigning by people like Dunn who organized efforts to register newly freed men to vote, thereby showing elected leaders the potential power of the black vote.

Some members of the Democratic Party in former Confederate states were opposed to the enfranchisement of African-Americans, and waged a war of misinformation and terror to keep black Americans from registering to vote. Black people were told their registration would be used to draft them into military service or that they would be lynched.

The threats didn’t stop Dunn from voting or running for office. In 1865, Dunn won a seat representing New Orleans’ fourth district in a Universal Suffrage State Convention. He also held leadership positions in other social welfare endeavors such as the Louisiana Association for the Benefit of Colored Orphans, the Freedman’s Aid Association of New Orleans, and a movement to establish a cooperative bakery. The People’s Bakery was a way to teach freed African Americans agrarian and business skills, and despite the fact it wasn’t commercially successful, it represented a first attempt by New Orleans’ black population to take control of their community’s economic destiny.

Despite a deeply factioned party, Republicans met in January 1868 to elect Louisiana gubernatorial candidates. There were essentially two divisions within the party: the Pure Radicals, who wanted to better conditions for freedmen, and the White Republicans. In his book Those Terrible Carpetbaggers: A Reinterpretation, historian Richard Nelson Current says the White Republicans wanted to use the black vote to reach office and then appoint “docile” black people to secondary positions within the government so they would “do the bidding of the White Republicans.”

Dunn was nominated for the post of lieutenant governor by P. B. S. Pinchback, a black Carpetbagger from Ohio and supporter of Henry C. Warmoth, who was elected governor in 1868. Dunn had serious reservations about running on the ticket with Warmoth, whom he felt would only use him to secure favor among black voters.

Dunn won the lieutenant governorship, despite being opposed by Democratic and independent candidates. He presided over the Louisiana State Legislature’s civil rights bills and the ratification of the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship to anyone born or naturalized in the United States, including former slaves. Warmoth ultimately betrayed Dunn by vetoing a civil rights bill that would have offered protections for black Americans.

Warmoth ultimately lost power. The Democrats wouldn’t support a Northern carpetbagger and Radical Republicans wouldn’t support a governor who didn’t work to bring protections for black people. There was talk of impeachment, which would have left Dunn as governor, but Dunn died before the governor’s impeachment trial.

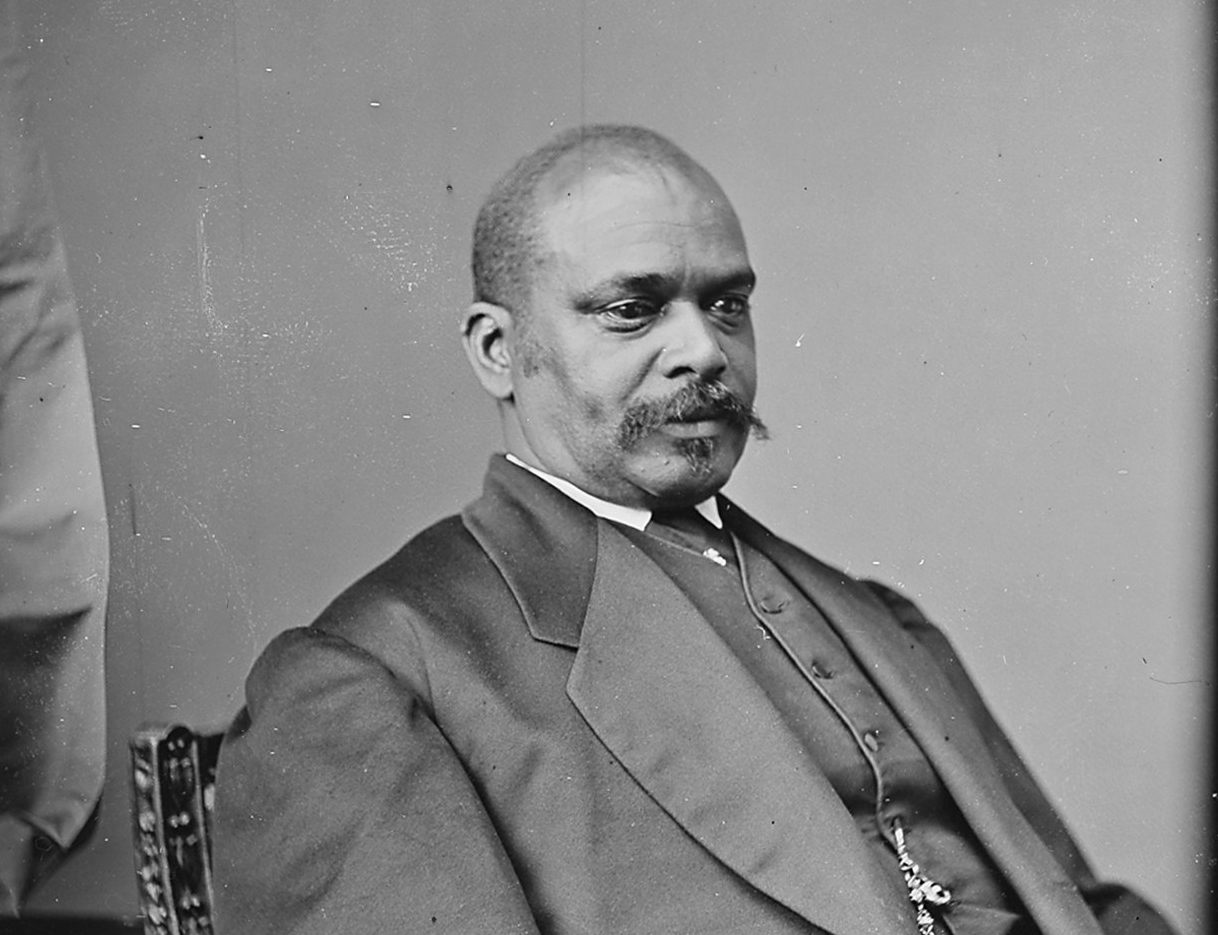

In 1869, and during his tenure as lieutenant governor, Dunn traveled to Washington D.C. where he sat for a portrait by Mathew Brady, the famed Civil War battlefield photographer. The portrait is one of the few remaining pictures that exist of Dunn. While in Washington, Dunn also had a audience with newly elected president Ulysses S. Grant, where he discussed political appointments.

Even though he was out of the Reconstructionist South, Dunn encountered mistreatment during his visit to the North. He wasn’t granted a sleeping car on a train, he was forced to share quarters with staff in a Philadelphia hotel while his white traveling companions were granted rooms and, as a joke, brokers hired a barber to impersonate the lieutenant governor during a visit to the New York Stock Exchange.

“The hoax at the New York Stock Exchange further elaborated the disrespect and maltreatment that the Lieutenant-Governor was subjected to as he visited the north,” Mitchell wrote in his dissertation. “The brokers who played the prank were not publicly admonished or disciplined for disrespecting a visiting dignitary.”

Shortly after attending a public dinner in 1871, Dunn became violently ill. He died two days later. The official cause of death was “congestion to the brain and lungs,” or natural causes. Several doctors examined his body, with some saying his death appeared to have been the result of arsenic poisoning.

Dunn’s supporters in New Orleans were shocked at news of his untimely death. His funeral brought the biggest funeral procession the city had witnessed to that point. Some 50,000 people took part in a second line—basically a parade—extending from Dunn’s home on Canal Street to Magazine Street. He was interred in St. Louis Cemetery Number 2 where mourners lingered until dusk to discuss his life and contributions to the Louisiana political scene.

Supporters held Dunn up as a hero, a martyred prophet whose mission to bring about political reforms for newly freed slaves was cut short. White political rivals in the Democratic party viewed Dunn’s rise to lieutenant governor as a “perversion of the natural order” and maintained that his contribution to the Louisiana political landscape was insignificant. They feared the “Africanization” of society and delighted when a popular black politician was no longer a threat.

Indeed, members of the Conservative Democrat party celebrated Dunn’s death. The Mystick Krewe of Comus made a mockery of Dunn and the Republican party’s efforts to establish equal rights for blacks. One of the first, modern Mardi Gras krewes, Comus was founded in 1857 and held a celebration and parade followed by a lavish ball on Mardi Gras night. At its annual Mardi Gras ball in 1873, the king of the krewe wore a gorilla costume in open mockery of Dunn.

Today, very little remains of Dunn’s legacy in New Orleans. His mansion on Canal Street is long gone and there are no paintings of him, or monuments on display. Dunn’s tomb was restored in 2000 by the Friends of New Orleans Cemeteries and a plaque installed with a brief account of his life. The only surviving portrait of Dunn is held in a private collection in California, Mitchell says.

As the nation’s first black lieutenant governor, Dunn’s legacy should be well known in Louisiana and elsewhere. But thanks to political rivals downplaying his contributions, he has largely been lost to history.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook