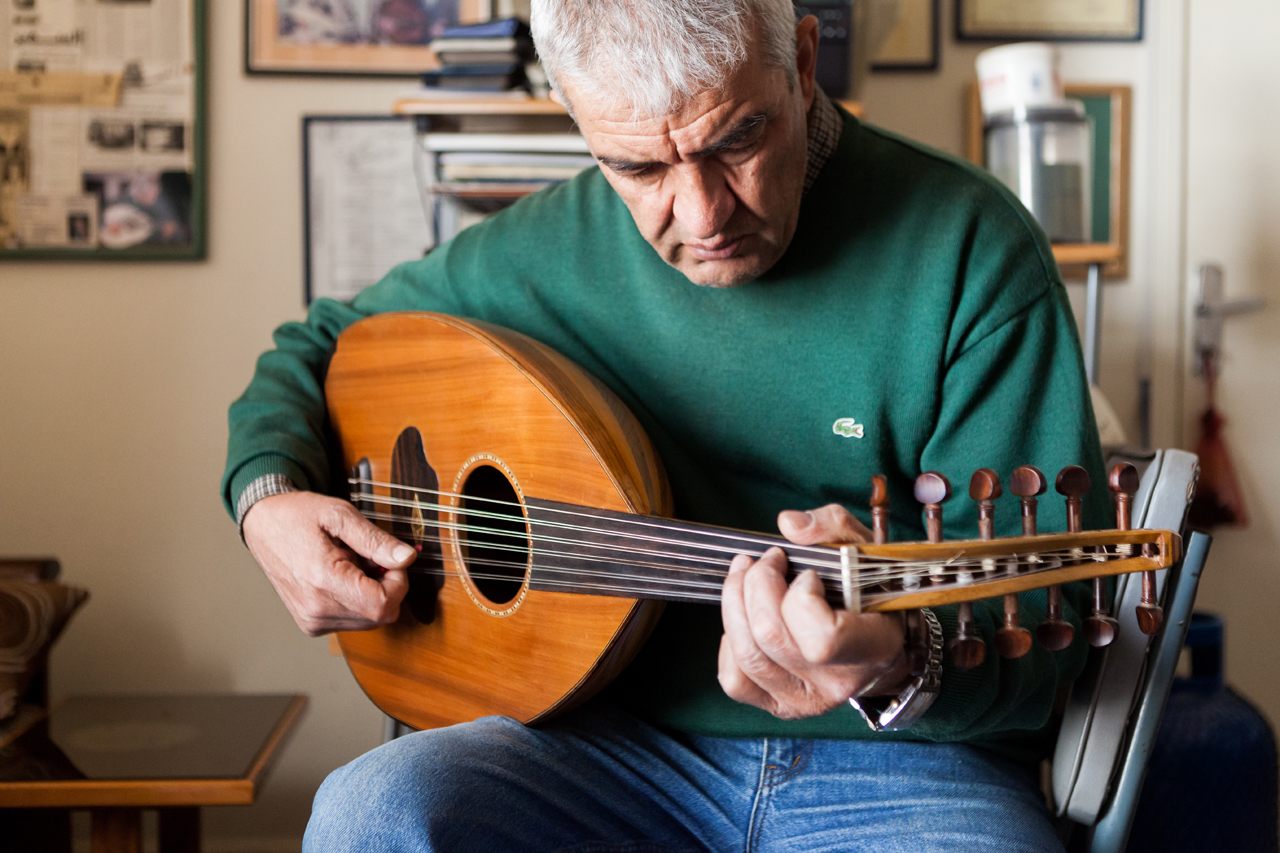

The Captivating Curves of the Guitar’s Arab Ancestor

In a workshop in Lebanon, an oud maker continues an ancient tradition.

“You can never make a good instrument from bad wood,” says Nazih Ghadban, an oud maker in Ras Baalbek, a small town in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. “But you can make a bad instrument from good wood.”

Ghadban reaches for one of the instruments hanging on the wall in his workshop, which is not far from the mountains that separate Lebanon and Syria. All around him are tools and stacks of small wood pieces. He strokes the back of an oud. It is soft and rounded, like an Anjou pear that has been cut in half—the distinctive shape of what may be the most beloved instrument in the Arab world.

Ghadban, who is one of few remaining oud makers in Lebanon today, has been making instruments in his workshop since 1976. “I was 18 when I started,” he says. “I have made 1,400 ouds since then, and none of them sound the same.”

The oud—or the “sultan of instruments,” as a poster on Ghadban’s wall says—has played a prominent role in Arab and Middle Eastern culture for a long time. Its exact origins are not entirely clear, but depictions of ouds have been found on excavated pieces in the Fertile Crescent; in ancient Persia, the four-stringed barbat was played more than 3,500 years ago.

“Very little has changed over the years,” says Ruba Hillawi, a teacher at the Taqasim Music School in London. “The body has increased in size and the neck made shorter, but its shape has not changed over the past 1,000 years or more.”

The oud made its way through the Arabian Peninsula and eastern Mediterranean before reaching North Africa and Andalusia, where its melodies filled the royal courts and spread to the rest of Europe. “That’s when ‘al-oud’ became the lute, and later on developed into the guitar,” Ghadban says. He smiles. “All Arabs know that the oud is the father of the guitar!”

He steps outside for a moment and comes back with a bottle of home-brewed wine. Ouds hang from the walls of the workshop with their rounded backs facing outward. Most do not have necks or strings yet: The work of mounting the wooden body always comes first. “That’s the most difficult part of the process. You have to work with water and a flame to bend the wood into shape,” Ghadban says.

In Arabic, the word ‘oud’ literally means a branch of wood, probably in reference to the ribs that form its pear-shaped body. Different kinds of wood are often used for the same instrument, an old technique to make it sound deeper and more distinctive. The famous lute maker Hanna Hajji Al-Awwad, from 19th-century Baghdad, is said to have used 18,325 pieces to make a single oud. Ghadban uses oak, mahogany, lemonwood, Indian rosewood, Burmese teak, and walnut, all imported from abroad. “Each wood has its own sound,” he says. “Ras Baalbek is perfect for this work: The weather is dry, which prevents the instrument from cracking and losing its sound.”

In recent decades, ouds have passed through the hands of prominent musicians such as Marcel Khalifeh in Lebanon, Munir Bashir in Iraq, and the “King of Oud” Farid El Atrache, who was born in Syria, learned to love music from his mother, and launched a long and celebrated career in Egypt. The fretless instrument is ideally suited for the Arabic melodic structure maqam, since it can play any musical interval without having to retune.

“This makes it a very versatile instrument,” Hillawi says. “One cannot produce quarter-tones using fretted instruments such as guitars, so musicians turn to the oud since it lends them the freedom to produce these notes.”

Some of the most prolific oud makers in history were the Nahat brothers from Damascus, only a short distance across the mountains from Ras Baalbek. The brothers, whose surname means sculptor, kept their workshop running from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s and created elaborate, ornate instruments.

Ghadban decorates his instruments in a similarly intricate way, using carved calligraphy and a woodworking technique called intarsia. He opens a drawer and takes out tiny geometric figures made from carefully pieced-together wood and bone, sometimes mother of pearl. This kind of decoration is used across the Arab world for everything from furniture to backgammon boards and boxes. Various kinds of stars are among the most common motifs.

“Humanity has always been interested in the heavens,” says the art historian Hala Auji at the American University of Beirut. “And there was a connection to science, in a time when astronomy and astrology were not seen as separate fields.”

The oud has also spanned many fields. It was praised in 9th-century Iraq for treating illness, and was sometimes brought and played on the battlefield; it occupied the early Islamic thinkers Al-Farabi and Al-Kindi. The latter is sometimes called the father of Arab philosophy. “All Arab philosophers were interested in music, particularly the oud,” says Ghadban, who was himself a philosophy teacher until he retired recently.

Ras Baalbek used to have several oud makers, as did Beirut. Today, Ghadban knows only one lute maker in the capital, and one in the coastal town of Jounieh. Turkey and Syria are home to more; in Cairo, where Farid El Atrache once lived, an entire section in the market is dedicated to instruments.

“Still, I am not worried about the future,” Ghadban says. “The oud is well and alive, and I have customers. And now that I’m retired I have more time to make ouds.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook