When Hard Rock Music Meant Banging on Actual Hard Rocks

The “shipwrecked Mozart” who wowed Victorian audiences, including the Queen herself.

An advertisement from the paper proclaims, in all caps, “ORIGINAL MONSTRE ROCK BAND.” A few lines below: “SOLID ROCK.” Nothing unusual there, because who doesn’t want to know where to find music that goes to 11? The only problem is that, in this case, the newspaper is from 1846.

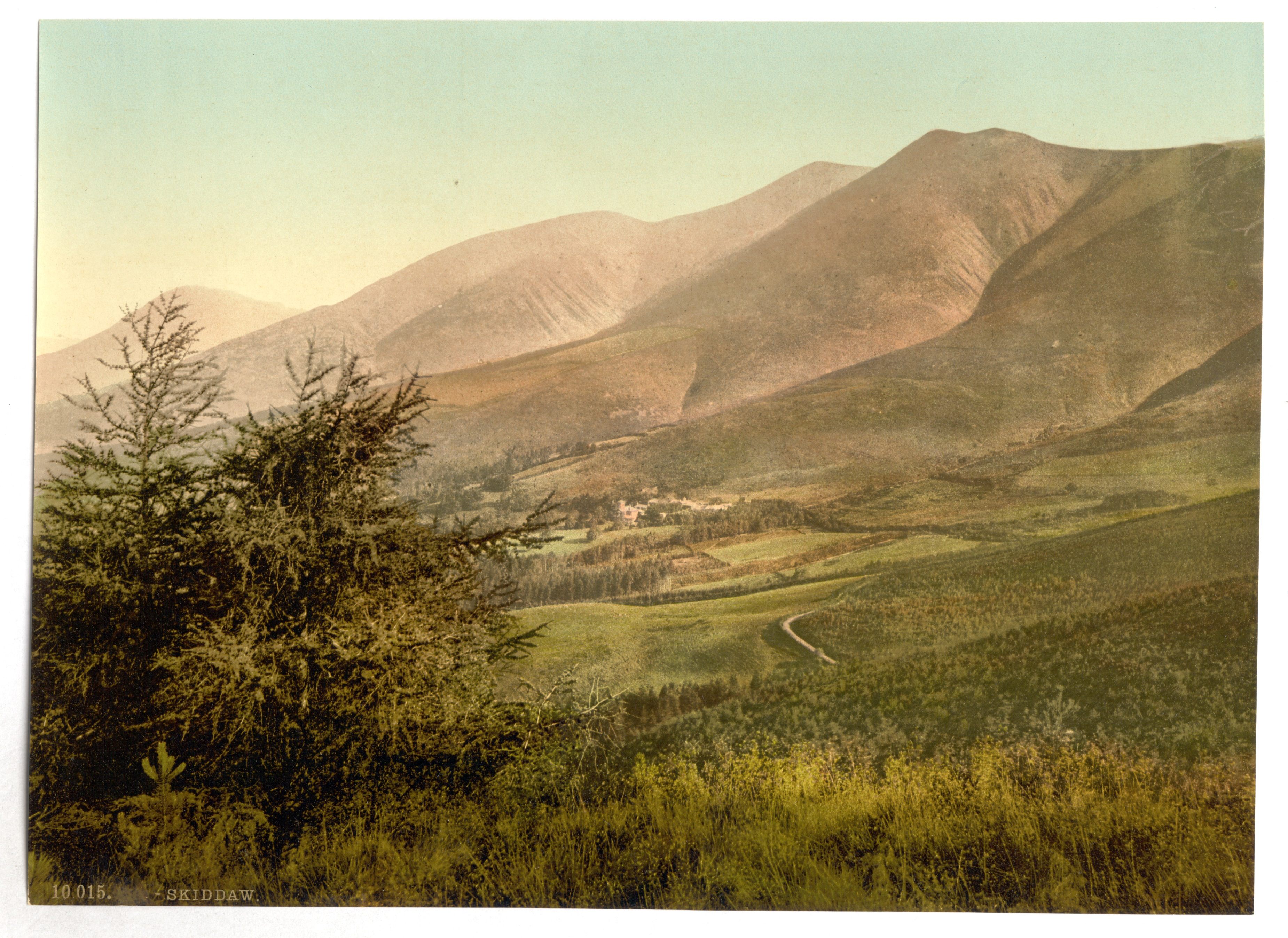

Concertgoers at the time probably wouldn’t have been ready for guitar feedback and drum solos, but they were eager enough to see a family making music with actual rocks, hewn from a volcanic mountain called Skiddaw (which, to be fair, sounds pretty metal).

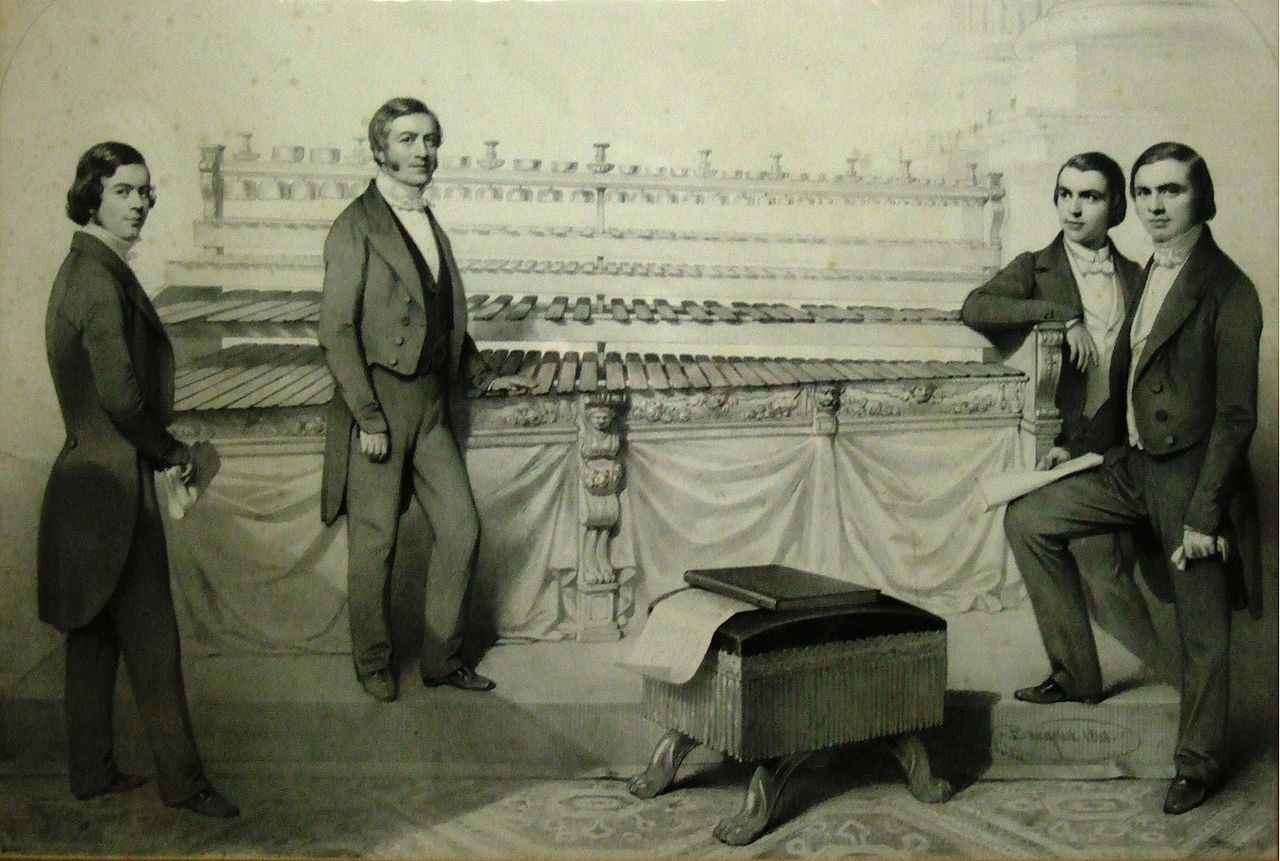

The Original Monstre Rock Band was the creation of Joseph Richardson, a stonemason from Keswick, England. Richardson had created what he called a “rock harmonicon,” one of a class of instruments called lithophones, which feature stone bars shaped, tuned, and assembled in the style of a modern mallet percussion keyboard, such as a xylophone or glockenspiel.

The resonant properties of local Keswick stone had first gained attention in the 18th century, when Peter Crosthwaite, proprietor of a local museum, built a small stone instrument that covered two octaves. Richardson would likely have known of Crosthwaite and his cabinet of curiosities. Being of the maker sort himself, Richardson got to work on a full-scale version.

Beginning in 1827, he spent 13 years carting and carefully chipping pieces of a metamorphic rock known as hornfels until he had an instrument composed of 61 stones, 12 feet long, with a five-octave range. The largest piece of stone was roughly three feet in length, an octave below middle C, and the smallest was a mere six inches long. Each note-producing slab was laid on twisted straw across a pair of long wooden bars. Players used an assortment of specialized wooden and leather mallets to play the instrument.

Lithophones such as Richardson’s work because of the specific nature of the rock. Just as a tapped wineglass goes silent when you put a finger on the rim, the vast majority of stones dampen vibrations nearly immediately because of their internal structure. Most rocks make no special noise to speak of.

Hornfels is different. This stone, and in particular the variety from the northern Lake District of England, naturally resonates to create a sound that can be very sweet and mellow. One article describes the rock harmonicon’s tones as “equal in quality and fullness to those produced on a piano-forte.” Modern acoustic engineer Trevor Cox is more circumspect in his assessment, noting that some stones indeed ring beautifully, “while others sound like a beer bottle being struck with a stick.”

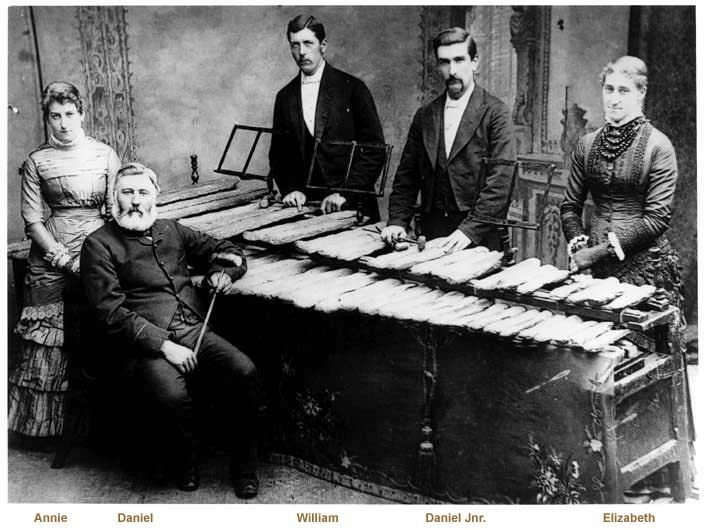

To play the harmonicon for audiences, Richardson’s three sons worked in frenzied concert, wielding mallets with heads the size of baseballs. Crowds were amazed with their intricate classical repertoire. A July 1841 issue of The Athenaeum raved about the Richardsons, calling the spectacle “like fabled things made real,” and comparing Richardson himself to “a shipwrecked Mozart” capable of calling forth beautiful music from the rudest, crudest, most improbable materials.

By 1845, the Original Monstre Rock Band was performing regularly at London’s Egyptian Hall, and played multi-week engagements at the Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens, amid traditional bands, animal feedings, and reenactments of the Siege of Gibraltar. They toured the country, and even played two royal command performances at Buckingham Palace, where Queen Victoria was said to have been delighted. (She was, apparently, a rock purist, and was displeased when the Richardsons chose to sully the show with the addition of steel bars the second time around.)

This style of rock music fit naturally into 19th-century entertainment culture, which was curious, occasionally inventive, and reckoning with industrialization. Also, audiences just enjoyed it. The addition of “Original” to the name of the Richardsons’ act had become necessary because there were several competitors trying to get in on the action. Copycats, however, were limited somewhat by the availability and unwieldiness of tuned instruments that could weigh as much as a saddle horse.

The Richardsons were followed in widespread fame by the Till family, who were particularly active in the 1880s, and made an acclaimed tour of the United States. In an effort to keep the novelty factor fresh on the road, rock bands came to offer add-ons such as additional instruments or new innovations. The Tills, for example, brought an Edison phonograph with them on tour. Technologies like that are what eventually put them out of fashion.

Lithophones are part of a long creative history of percussion, and they are still in use today. The Richardson’s massive instrument can still be played at the Keswick Museum & Art Gallery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns one of the Till instruments, there is a tradition of similar instruments in Asian music, and modern manufacturers continue to make lithophones for both art and amusement. Edward Troxell, a college professor who also served as Connecticut’s state geologist, manufactured his own “Stone Age Steinway” in the 1940s, using rocks he gathered during fieldwork on and around Avon Mountain. Though a skilled craftsman, he was no great musician and somewhat sheepishly admitted to the Hartford Courant that he could only manage to play “Chopsticks” on his creation.

Naturally occurring ringing boulders have been discovered in locations from Pennsylvania to Azerbaijan. Some also speculate that even Stonehenge was some kind of giant resonant stone instrument. According to Thomas C. Duffy, a composer and Director of Bands at Yale University, this should be no surprise. “For centuries, instrument makers have experimented with the sonic qualities of wood, bone, brass, steel, bronze, and metallic alloys; and quartz, glass, and other stones,” he says. “Stone instruments—less practical because of their weight, mass, and fixed timbre—resonate with a sense of primitive purity. Although some stone ‘instruments’ are sculpted and shaped into tuned strikers, others, like the Luray Caverns Stalacpipe, are presented in their natural state.”

All of this is to say that the human impulse to whang away on whatever is around us a longstanding tradition, and it bears meaning. As one happy reviewer wrote of the Richardsons, “Truly this is bringing home to our hearts the poetry of common things.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook