The Most Interesting Camel in the World

Before she retired to L.A.’s Griffith Park Zoo, Topsy was a soldier, a builder, a miner, and a movie star.

On April 27, 1934—squeezed between items about liquor taxes and club baseball—readers of California’s Madera Tribune were treated to an unusual obituary. “LAST AMERICAN CAMEL IS DEAD,” mourned the headline. “Topsy was the last survivor of the camel herds that once carried packs across the mountains and lava beds of Arizona and southeastern California,” the article beneath explained. “…Some of the survivors were later captured and sent to zoos and among them was Topsy.”

Not a bad public tribute for a camel—most don’t get obituaries at all. But Topsy’s life was far too storied to fit into a couple of column inches. From what experts can tell, Topsy wasn’t just the Last American Camel, but one of the first. Over the course of her 81-odd years, she was an immigrant, a soldier, a builder, a miner, and a movie star. She had a hoof in everything from the U.S. Army’s ill-fated Camel Corps and the construction of what would become Route 66 to the rise of Hollywood and the circus industry. Taken together, her exploits make her something of a Forrest Gump of camels.

Topsy’s early years, which she likely spent in Egypt, are lost to us. What we know of her tale begins in the 1850s, when the United States Army began exploring their options for westward travel and realized there really weren’t any. Several concerns—including an influx of prospectors and frontiersmen heading West, escalating conflicts with Mormon towns in Utah, and the possibility that a foreign power might attack California—convinced the Army that it was time to start building a route that led through the wilderness and to the coast.

The Army began to hire human civilians to help build this road, but they quickly realized they would need to provide an unusual type of four-legged support. “Mules and horses just didn’t last long in the wilderness—the deserts you get after you leave Kansas and Nebraska,” says Forrest Bryant Johnson, author of The Last Camel Charge: The Untold Story of America’s Desert Military Experiment. A different sort of steed was needed.

Throughout the 1830s and 40s, various Americans had floated the notion of using camels in the American Southwest. Eventually, a Pennsylvanian named Josiah Harlan—who had served as a military commander in Afghanistan and returned to the U.S. as a consultant to the War Department—brought the idea to the Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis. Riflemen in Afghanistan often rode camels, Harlan told Davis, and the animals were exemplary: They ran fast, stayed calm in battle, could carry heavy loads, and, of course, needed very little water.

Davis thought it was worth a shot, and in 1855, after about a year of trying, he managed to convince Congress to give him a $30,000 camel budget. Soon after, a retired U.S. Navy ship, the USS Supply, set out for Tunisia, Egypt, and Turkey. Overall, the ship picked up about 35 camels, who enjoyed a spacious stable with glass portholes, a fresh air hatch, and harnesses for rough weather, all especially installed for the trip. They were brushed daily and fed gallon after gallon of oats and hay, though that didn’t stop them from eating the whitewash off the ship walls.

The Supply made it to Texas, unloaded the camels, turned around, and went back to the Middle East to pick up a few dozen more. It’s unclear exactly which trip she came in on, but one of these camels was Topsy, a Bactrian, or two-humped, variety known for their speed, and their tolerance for difficult weather.

It’s hard to say whether Topsy and her companions were happy to be in America, but according to eyewitness reports, they were certainly pleased to be back on land. “Feeling once again the solid earth beneath them, they became excited to an almost uncontrollable degree,” wrote one of their handlers, Lieutenant David Dixon Porter. “Rearing, kicking, crying out, breaking halters, tearing up pickets, and by other favorite tricks [they] demonstrated their enjoyment.”

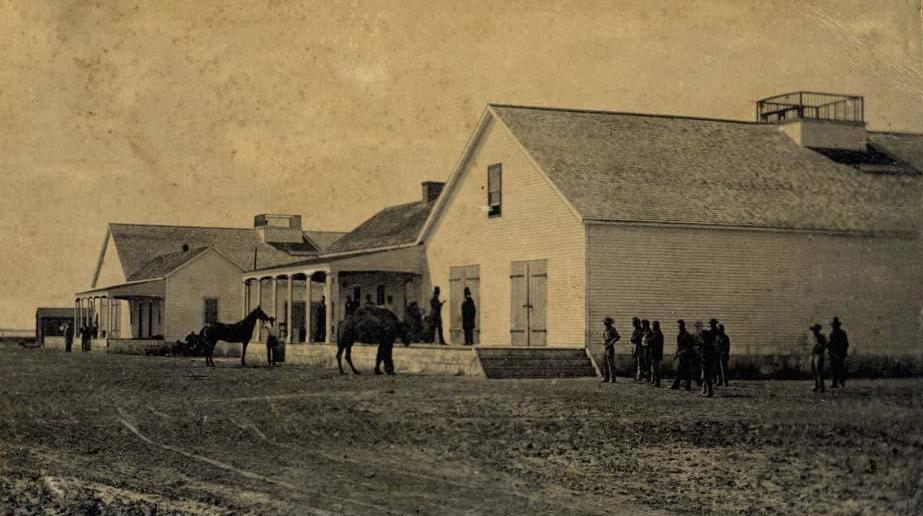

Soon after, the camels set out on their first march, from the Texas coast to their new barracks in Camp Verde, near San Antonio. They were led by several Greek, Arabic, and Turkish handlers who had been hired overseas for their camel expertise, including Hadji Ali, nicknamed “Hi Jolly.” Hi Jolly and Topsy would stick close together for decades to come.

For a few months, the camels enjoyed an easy life on the corral. But eventually, it was time to get to work. Lieutenant Edward Beale, who had been put in charge of the road building project, selected 25 camels that looked construction-ready. (Based on where she ended up later—and her association with Hi Jolly, who also went on the trip—it’s likely that Topsy was one of these.) Moving through Arizona, the camels wreaked gentle havoc as they passed through small settlement towns, spooking horses with their unfamiliar smell and eating the locals’ cactus fences.

Their human companions, though, were charmed by their personalities and hauling skills. “As individual units became familiar with the animals, they were really quite fond of them,” says Johnson. As the expedition moved along, Topsy and her fellow camels lugged supplies and tools, and the humans cleared rocks and brush out of a continuous ten-foot swath, laying out what was then known as the “military wagon road.” This track would eventually become the westernmost part of America’s most famous highway: Route 66. “You can attribute Route 66 to the camels in this way,” says Johnson.

The Army, impressed with their new recruits’ performance, retained hope that they would be an asset in military situations as well. The camels’ endurance and speed—especially compared to that of the horses and mules that had accompanied them on the road-building journey—convinced the army that they’d found “a new superior weapon,” says Johnson. But before the camels could prove their worth in this way, a more pressing conflict boiled over: the Civil War. The resources that the Army had dedicated to the camels were needed elsewhere, and the project was disbanded.

After the breakup of the Camel Corps, the group’s veterans scattered. Many of the camels that stayed in Texas were captured by the Confederate army and used for entertainment purposes—in Johnson’s words, “to ride the pretty girls around.” Some were set free and lived out their days in the deserts of the Southwest, mystifying cowboys and frightening cattle. At least one, named Old Douglas, was adopted by a southern regiment, and eventually killed by Union soldiers at the battle of Vicksburg. (“All who saw the murder were highly incensed,” wrote one observer after the fact.)

On February 26, 1864, most of the California camels were auctioned off by the government. It’s unclear exactly where Topsy ended up during this time, but it’s possible that she, like many of the Bactrians, set out with Hi Jolly for a ranch in Nevada, where camels were put to work hauling salt and firewood at the Comstock Lode silver mines. After Nevada outlawed the use of camels on highways, citing their tendency to spook horses, most of this herd moved on to Arizona to do similar work.

Although her exact mining credentials remain unknown, there was another popular camel career track Topsy definitely pursued: show business. By this point, Americans were more than willing to hand over cash to see what the papers of the time described as “prehistoric animals with gangling limbs and long, arched necks,” and Topsy was a natural. She performed with the Ringling Bros. Circus, marched in street parades, and even got some onscreen gigs with Fox Film Corporation, where she helped set the scene for various desert romances.

Tragically—and ironically, considering her earlier pursuits—it was this particular straw that proved backbreaking. While traveling to a showbiz job, Topsy was involved in a train accident. She injured both of her humps, and her mate, whose name remains unknown, was either killed or badly burned in the crash.

After the wreck, Topsy was taken in by the Griffith Park Zoo, in Los Angeles, where she lived out her last years. As Hadley Meares details in an article for KCET.org, she was the zoo’s most popular resident during the 1920s and early ’30s. The press, too, treated her with some reverence: “From comfortable quarters in old Griffith Park… old Topsy, a veteran Bactrian, watches the visitors go by,” wrote the Baltimore Sun in 1931. “She observes them with an eye of tolerance, having seen much and traveled far in a colorful and eventful career.”

According to the Sun, Topsy shared her cage with two whippersnappers: a 6-year-old male named Prince, and a 7-year-old female named Vanity. As she aged, her injuries worsened, and in April of 1934, at roughly age 81, she was put to sleep. She was cremated, and about a year later, her ashes were sent to Quartzsite, Arizona, where they were buried alongside her old friend, Hi Jolly.

Now, 83 years later, the Griffith Park Zoo has been abandoned. Many of Fox Film Corporation’s reels, containing Topsy’s starring moments, were destroyed in a fire. Route 66 is decommissioned and crumbling, and the tourists who still choose to drive it likely know little about the road’s many two-humped progenitors.

The West, though, is full of people. Next time you find yourself there, take a moment to remember Topsy, the camel who helped make that possible.

You can see the ruins of the Old Griffith Park Zoo on Obscura Day, May 6, 2017, and hear more about Topsy’s time there at the Abandoned Zoo Ruins tour in Los Angeles.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook