Object of Intrigue: The Most Beautiful Banknote in U.S. History

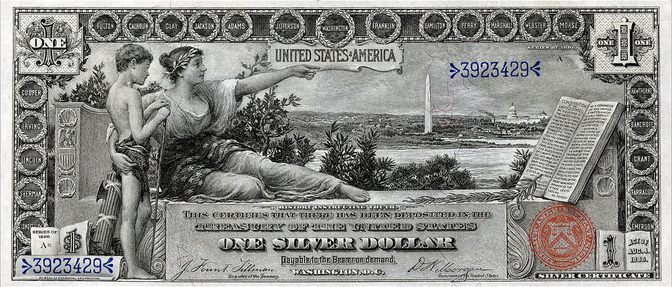

Detail from the obverse of the United States $1 silver certificate, issued in 1896. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution on Wikipedia)

Art and money have a complicated relationship in America. But art on money has always been pretty simple: Put a dead president on the front of a note, some numbers and a seal on the back, and cover the whole thing in a lot of squiggly lines to make it harder for people to print their own cash.

This hasn’t always been true, though. Back in the 1890s, there was a conscious effort to turn American money into pocket-sized works of art. It resulted in the creation of what is still regarded as the most beautiful set of bank notes ever issued in the United States: the Educational Series of silver certificates.

Silver certificates, issued between 1878 and 1964, were a type of representative money that could be traded in at a bank for their face value in silver dollar coins. As with most paper currency in the United States, silver certificates usually featured a portrait of a deceased president on the obverse side of the note, which was printed with black ink. The reverse side, most often printed in green, tended not to depict any presidents or pioneers, but instead had ornate, intricate designs that swirled around the numbers and lettering to help prevent counterfeiting. In the case of the 1886 $5 silver certificate, pictured below, there was even an illustration of coins on the reverse—money depicted on your money.

The 1886 $5 silver certificate. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

By the 1890s, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP)—the government agency that controls what designs appear on the nation’s paper currency—was open to the idea of a money makeover. With the United States innovating and industrializing, it seemed an apt time for the nation’s progress to be reflected on the art of its bank notes. And the standard dead-president design was getting a bit tired: a New York Times article from March 3, 1896 acknowledged that “there has been for a long time a desire to make a change in the inartistic and stiff paper currency of the years that have gone.”

In an effort to bring more artistic merit to the silver certificate, the BEP approached Edwin Blashfield, Will H. Low, and Walter Shirlaw, three artists known for their elegant allegorical paintings. As muralists, Blashfield and Low were accustomed to working at a much larger scale than the 3.125-by-7.4218-inch dimensions of a silver certificate. But the painters’ flair for eye-pleasing composition and their ability to translate principles of national character into gorgeous tableaus of women in flowing robes was paramount. They were encouraged to submit large paintings, which a team of skilled engravers could then translate to currency-compatible format. According to the aforementioned Times article, 15 to 20 engravers worked on each note, each one assigned to a particular section of the design.

The resulting three artworks formed the basis for the $1, $2, and $5 silver certificates that came to be known as the 1896 Educational Series. Here is a closer look at each note.

The $1 note, with artwork by Will H. Low. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

The $1 note, with artwork by Will H. Low. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

The unofficial “Educational Series” name, used by numismatists, comes from the title of the artwork on the $1 bill: History Instructing Youth. As shown above, History is portrayed as a woman. She sits with her right arm around a young boy, representing Youth. Her left arm points to a book that contains the United States Constitution, the opening words of which are legible to the naked eye. In the background is the then-recently completed Washington Monument, as well as the Capitol Building. Twenty-three wreaths around the edge of the note encircle the names of men who made significant contributions to the development of the nation.

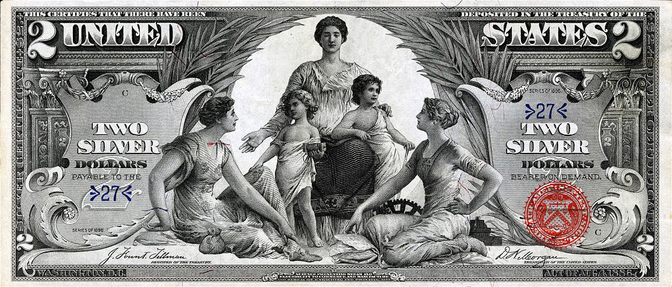

The $2 note, with artwork by Edwin Blashfield. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

The $2 note, with artwork by Edwin Blashfield. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

The art on the $2 is entitled “Science presenting Steam and Electricity to Commerce and Manufacturing.” In an August 1896 article introducing the new silver certificates, the New York Times described it thusly: “The centre figure is Science, a woman in Greek garb. To her right stands an infant grasping a small throttle, and to her left another bearing a galvanic coil. Commerce and Manufacture, two graceful women, stand ready to receive Steam and Electricity, respectively.”

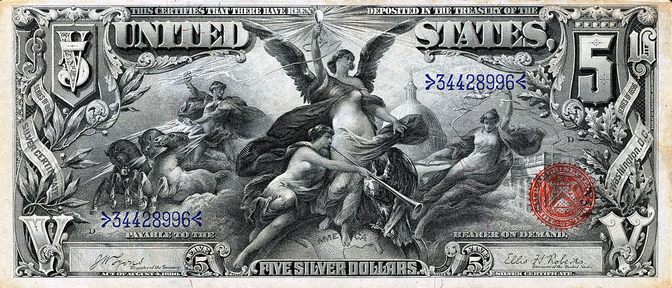

The $5 note, featuring artwork by Walter Shirlaw. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

The $5 note, featuring artwork by Walter Shirlaw. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

The same Times article also detailed the look and meaning of the $5 note: ”The winged figure of a woman, ‘America,’ stands upon a globe, her feet touching the map of North America. In one hand she holds aloft an electric lamp, fed by a ribbon floating in graceful curves to a bursting thundercloud. Additional allegoric figures are ‘Jupiter,’ representing force, standing upon the backs of a span of spirited steeds, ‘Fame,’ proclaiming the nation’s progress through a long trumpet, and ‘Peace,’ with her dove.”

Among collectors, the Educational Series is highly prized. ”It is still the single most popular set of US currency,” says Manning Garrett, Director of Banknote Auctions at Manifest Auctions. “Many notes are rarer and many notes are more valuable, but the educational set is always the most popular.”

Of the three notes, says Garrett, ”the five-dollar note is generally considered the most attractive piece of currency the US ever issued.” Though the notes typically sell for $300 to $3000 depending on their condition, “especially nice examples can be worth as much as $30,000.”

Given the high esteem in which the Educational Series is held, you might wonder why the U.S. soon went back to the dead-presidents design that still dominates paper currency. There are stories of people being outraged by the bare breast of the woman embodying America on the $5 Educational Series note, but such tales can’t be the reason why an entire series of innovative and beautiful notes didn’t usher in a new era of currency design.

“I don’t doubt that some people might have had an issue with it,” says Garret, of the apparent scandal. “However, the US had issued currency with bare-breasted women as early as the 1860s. So it would have been old news by the 1890s and I don’t think the government ever seriously considered taking it out of circulation.”

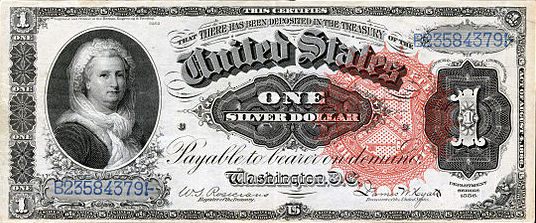

Given the politics of the time, the 19th century was pretty innovative when it came to depicting women on currency. Martha Washington appeared alongside her husband George on the reverse of the $1 Educational series note. But that wasn’t even her debut: years earlier she appeared—by herself—on the front of both the 1886 and 1891 $1 silver certificates.

The 1886 $1 silver certificate, featuring Martha Washington. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

Earlier this year, a non-profit organization, Women on 20s, led a campaign to put a woman on the American $20 bill. The 10-week campaign resulted in hundreds of thousands of votes, and the announcement of a winning candidate: Harriet Tubman. A petition was delivered to President Obama in May, with the hope being that the $20 could be redesigned and issued before the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in 2020.

Three years after the Educational Series debuted, the U.S. government issued a new series of silver certificates. They looked like this:

The $1 silver certificate of 1899, featuring Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses Grant. (Photo: National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution)

The Educational Series was a indeed a brief and beautiful rarity. As Garrett explains:

“Almost all previous issues had featured portraits of dead politicians. Most other previous issues also had white space in the design. The educational series didn’t feature any known persons. Every inch had some kind of vignette or engraving. Starting back in 1899 the currency designs were pretty much back to usual, that being a portrait, an engraving, a seal, and serial number. So 1896 notes are a bit of an outlier in that way.”

The three silver certificates in the Educational Series are among 250 notes currently on display at New York’s Museum of American Finance, in an exhibit titled America in Circulation. The Smithsonian’s National Numismatic Collection in Washington D.C. also has a full set of the 1896 notes, while the Money Museum in Chicago has the $5—see it for yourself and decide whether it really is the most beautiful bank note ever released in the United States.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook