How North Carolinians Learned to Love Their Green Oysters

The seasonal delicacy was discarded for decades.

This past March, at the Charleston Wine + Food festival, I ate a green oyster. I had politely passed at first, taking them for a misguided marketing fad. But after being cajoled by a chef-friend, I discovered that North Carolina’s green gill oysters are just as good as their boosters promise.

“These oysters provide a flavor unlike any other,” says chef Chris Hathcock of Husk Savannah. “A perfect balance of salinity and creaminess.” Matt Register of Southern Smoke BBQ likens their taste to a Carolina salt marsh, and describes them as slightly brinier than a regular oyster.

Yet for decades, these pretty oysters were sold at a steep discount, or even thrown out. Diners didn’t care to try green seafood. It’s only through the efforts of local chefs and oyster harvesters that green gill oysters, the product of the equally vibrant algae in North Carolina’s waters, have begun to be seen as a delicacy rather than trash.

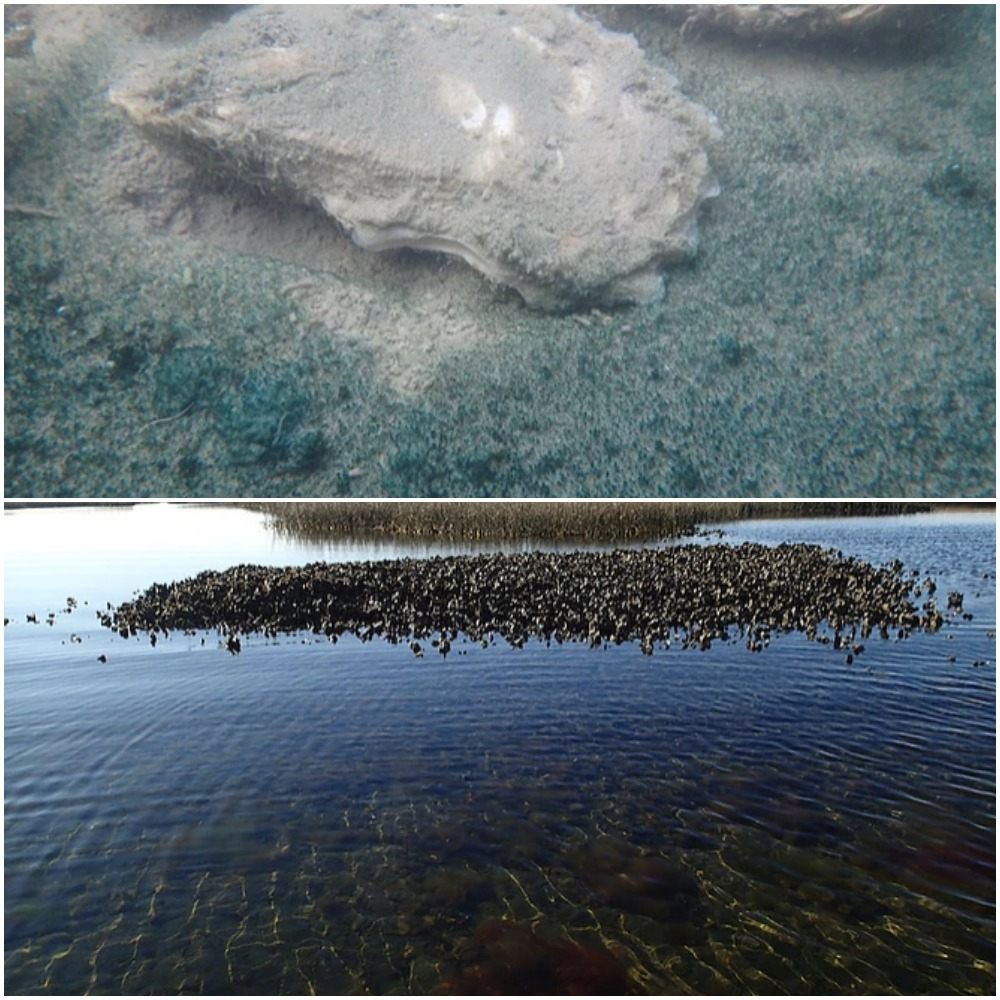

Each winter, for decades, Dave “Clammerhead” Cessna has found green gill oysters in his beds. “Oysters take in a diatom known as Haslea through their natural filtering process,” he explains, “and the algae gets embedded in the oyster’s gills.” Diatom, a type of blue microalgae, finds its way into oyster gills up and down the East Coast. In the colder months, when the water is clearer, Cessna says, more sunlight reaches the algae and allows it to flourish. But the coast of North Carolina, where Cessna’s beds are located, bloom bluer than just about anywhere else.

One exception is the clay ponds of Marennes-Oléron, France, where oyster harvesters carefully maintain the Haslea in the bright-blue water to produce fines de claires, their celebrated oysters that attain a similar green hue.

The French may celebrate their green oysters, but they were a tough sell in North Carolina. Cessna was the first to market the oysters, dubbing them Atlantic Emeralds and charging a premium for them. “Along with the unique flavor of the diatom,” he says, “the diatom enhances the oyster’s own flavor with an effervescence that lingers in a very pleasant way.” Other harvesters and restaurants were able to follow his lead.

“The success of green gills here in North Carolina [depends] on retailers and restaurants educating customers,” says Sarah Grace Smith of Locals Seafood. “I mean, they are green.” She explains to customers how their flavor can be earthier and more complex. Some are intrigued; others order them as a dare.

To aid in that education effort, some harvesters think carefully about which restaurants and eateries have diners’ trust. Ryan Gadow, of Three Little Spats, in Wilmington, searches out well-respected restaurants all over the East Coast.

Other green-oyster boosters get more creative. Chef Stephen Devereaux Greene of Herons, inside the Umstead Hotel and Spa in Cary, serves green gill oyster soup dumplings, a play on Xiao long bao, to highlight the delicacy in an artsy, abstract way. “We sell them as being a very exclusive find and as fresh as you can get,” he says. “Plus it’s the only oyster we use.”

These efforts have attracted the attention of local food media, who spread the message, and it has helped that the green-blue hue lends itself to the Instagram age. Chefs say they still have to answer questions about if green gills are safe to eat, but the oysters are increasingly seen as a spring specialty. “Much like shad roe or soft shell crabs,” says Smith. “You have to enjoy them while [you] can.”

The seasonal oysters are hard to find much later than May, and bad weather, such as last year’s Hurricane Florence, can put a real hurt on supply. This differentiates them from France’s green oysters, which are produced in a more controlled environment. While many local chefs seek out North Carolina’s green oysters, chef Sean Fowler, of Mandolin, in Raleigh, looks forward to the sporadic surprises in deliveries, which I imagine is equivalent to scoring the toy in a Cracker Jack box. “It’s a natural phenomenon that we get to enjoy briefly each year,” he says. “It makes them more elusive and more desirable.”

The rising popularity of green gill oysters is a bit of a double-edged sword, since the demand has made them harder to find. But most people in the industry think it’s worth it. “I am of the mindset that when you can get them, let’s celebrate them,” says Fowler, “and when they are gone they are gone.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook