The Professional Mourners of Mani, Greece

The peninsula is home to a tradition of ritual lament that dates back to ancient times.

The sound is indescribable, a primal howl. If I’d not seen the source of the wailing with my own eyes, I wouldn’t have believed it. Hunched over my grandfather’s body were three slight, elderly women dressed all in black, heads covered so that their eyes and mouths seemed to be lit like an El Greco painting. Though they weren’t imposing in stature, they made the military men beside them seem feeble.

These women are some of the last remaining moirologists, or professional mourners, in Mani, Greece.

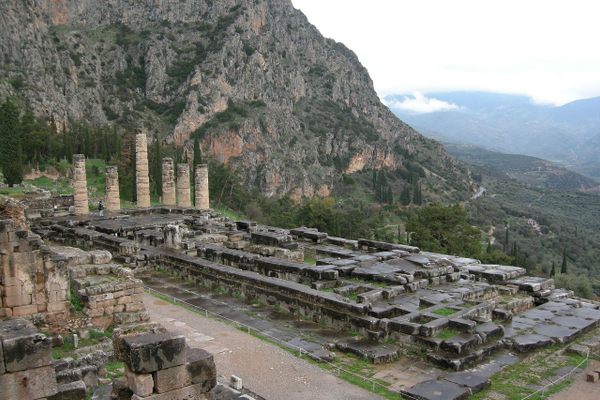

While most know Mani, the center peninsula in Southern Greece, for its breathtaking cliffs and quaint coastal villages, it also is home to a tradition of ritual lament that dates back to ancient times. Considered an art, moirologia can be traced to the choirs of the Greek tragedies, in which the principal singer would begin the mourning and the chorus would follow.

The origins of this particular tradition go back to at least the eighth century B.C., and started with family and friends improvising laments during the prothesis, when the body was set out in its former residence. Over the centuries, it became a profession exclusive to women. Those who were especially adept at this improvisation, and could endure the physical and emotional traumas of the work, were hired by families to lead in the ritual lament.

While the particulars of the ritual can vary, the general arc of the proceedings remains similar. To begin the ritual, the moirologists, sometimes alongside the women in the family, lay out the corpse; wash the body with wine, vinegar, or water; seal its orifices; and dress it in fine clothing, something the deceased might have worn to church. Candles are placed at the head and the feet, and flowers—particularly scented herbs like basil, marjoram, and mint—are scattered. Then a coin is set on the forehead or mouth of the deceased to ward off evil spirits.

In the afternoon, friends and family assemble at the house of the deceased. As each mourner reaches the outer door of the house, the moirologists begin to repeat the word adelphia, which means “brother” or “sister.” The closest female members of the family and the moirologists stand around the corpse. The most respected of the moirologists, usually one of the eldest, begins the lament.

As the momentum builds, the moirologists, sometimes accompanied by the other women present, remove their shawls and take down their hair, slowly pulling at the strands, swaying in time with the chant. The verbal aspects of the lament can start in a handful of different ways. It may begin with praise for the dead, or it may start with a farewell to life from the point of view of the deceased.

These moirologists weave together religion, mythology, and village history in an impromptu performance to describe the life of the person being mourned, his relationship to those present at the funeral, and his journey to the afterlife. Young descendants of Mani have likened this quick thinking to a rap battle.

When each woman finishes her part of the story, she both figuratively and physically transfers the lament to her successor, stretching her hand over the corpse to touch the hand of the woman who will continue the performance. As the woman crafts her story, the others continue their unceasing wails and moans.

The moirologists must be precise. There must be no break in the lament, as interruption is a grave omen for both the soul of the deceased and those present. Furthermore, they cannot begin the ritual too soon after death because it will prevent the soul from leaving the body.

The mourning ceases at sunset and all women are silent until the following sunrise. One moirologist stays to guard the body.

At dawn, the mourners—relatives, friends, and professionals alike—return. The priest performs a sermon and the body is carried to the cemetery, where the lamentation continues from the perspective of long-departed souls, who are asked to take care of the newly deceased person during his journey to the afterlife. The dead give instructions to the mourners, including the performance of memorial rites, which take place on the third, ninth, and fortieth days after death, as well as the first anniversary.

During these memorial rites, both relatives and the moirologists make offerings, including locks of hair, oil, perfume, wine, honey, and garlands. The mourning period finally concludes after three years, when the body is dug up and placed in the village ossuary or family mausoleum. It is only at this point that the soul is said to be released to the afterlife.

Raised in the United States, I had never seen such an outward embrace of grief before my grandfather’s funeral. Seeing these women openly and emphatically weep over his grave allowed me permission to feel my own emotions and express them. While these laments were initially created to assist the deceased on their passage to the afterlife, they ultimately served to help me on my journey to acceptance, a purpose they have served for centuries.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook