Mistletoe Is a Parasitic, Explosive Plant That Maybe You Shouldn’t Stand Underneath

Mistletoe on a doorway. (Photo: Teodora D/shutterstock.com)

The mistletoe plant is largely known for a manufactured characteristic: It’s the green sprig with white berries that hangs in doorways during Christmas time, requiring those who meet beneath to kiss.

But here’s the thing about this festive accessory: It’s a parasite.

Yes, the mistletoe attaches itself to other plants and sucks the life out. It’s also one of the few plants that actually propel its seeds (at speeds up to 60 miles an hour) out of its own berries. As a home and food source for birds, butterflies and bees, the mistletoe plant is a crucial part of the world’s food chain. Being a makeout-instigator may be the least interesting thing about mistletoe.

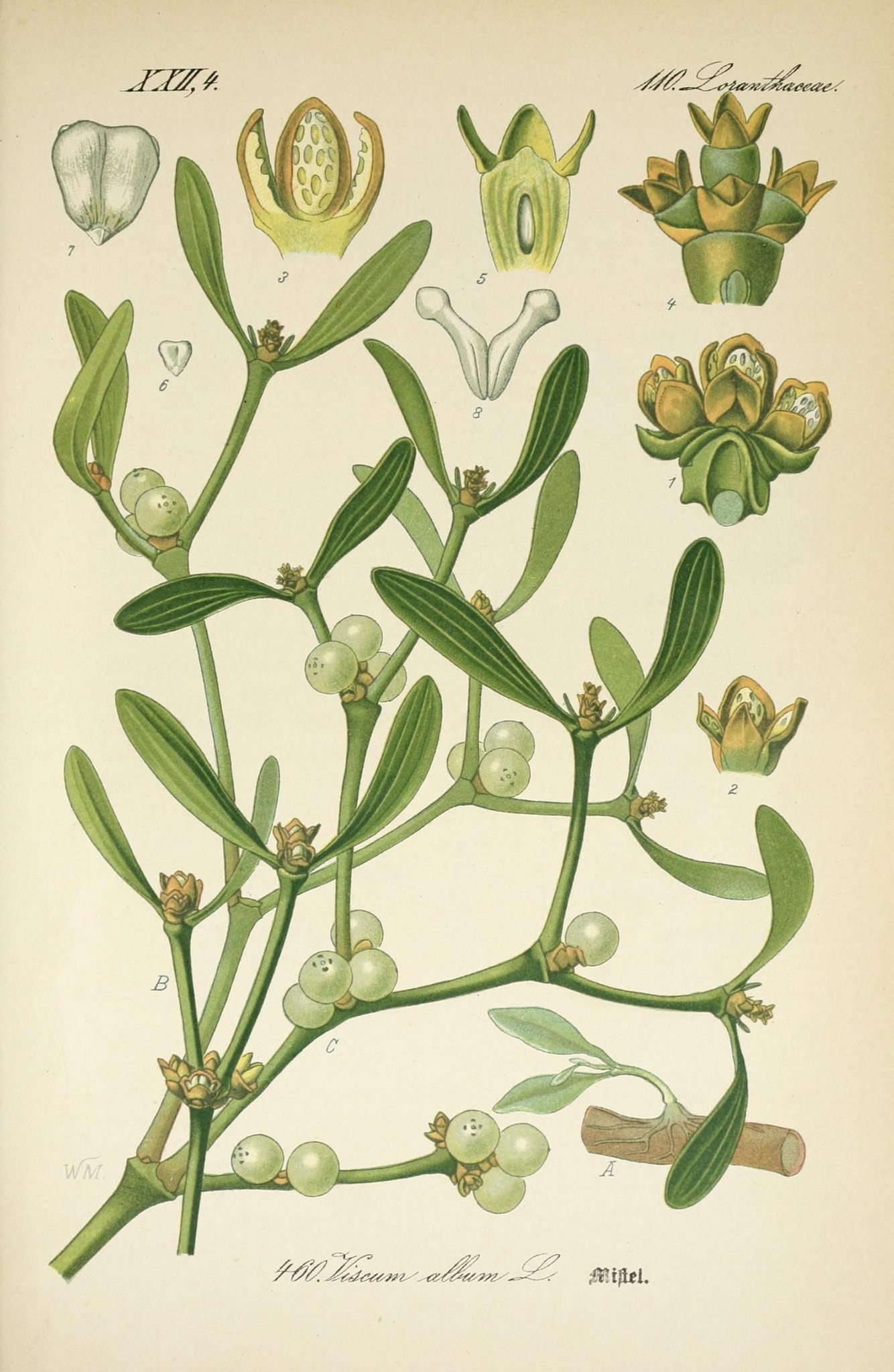

An illustration from 1917 of Phoradendron leucarpum, American Mistletoe. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Todd Esque is a research ecologist for the U.S. Geological Survey based in Henderson, Nevada with over 30 years of experience studying desert tortoises, with forays into Mojave ground squirrels, Joshua trees and rare cactuses. He’s also fascinated with mistletoe. Whenever Esque travels, he keeps his eyes peeled for mistletoe-related research and tries to learn all he can in order to be a resource on the plant.

In the early 2000s, Esque was asked to assist a graduate student who was studying the plant; at the time the assignment almost seemed like a mistake to Esque, who had no expertise in mistletoe. But the one-time gig turned into an obsession. “When they suggested that I don’t need to do it anymore, I was like no, no, no,” says Esque. “This is the most fun I get to have—talking to people about mistletoe and learning about mistletoe.”

There is a lot to love about mistletoe, according to Esque, such as its under-appreciated sweet fragrance and the fact that it flourishes during February in the desert, when little else is blooming.

Waiting under some mistletoe. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In the United States, there are two native species, dwarf mistletoe and American mistletoe (of Christmas-kiss fame). Worldwide, over 1,300 varieties grow. There are mistletoes in hues of pinks and yellow and mistletoes that resemble sticks and twigs.

One of its least known qualities is the thing that really drew Esque to the plant—it’s relationship to other trees and shrubs. Specifically, mistletoe is a hemiparasite.

“In order to entirely be a parasite, it wouldn’t have any photosynthetic abilities,” says Esque. “The reason it’s a hemiparasite is because it can produce some of its own energy.”

Mistletoe attaches itself to trees and shrubs, penetrating the host in order to siphon away water and nutrients. But it can also use photosynthesis to nourish itself, so it is not a total parasite. Mistletoe is not beloved by arborists because it stunts the growth of trees and can kill them. But mistletoe also plays an important role in many ecosystems.

“Parasite has a negative connotation in almost any context,” says Esque. “And yet, as you start to learn more and more you find out there are reasons these organisms are out there and they have a place in the community.”

A late 19th-century illustration of mistletoe. (Photo: Biodiversity Heritage Library/flickr)

Among mistletoes benefactors are the Silky-flycatcher, a small bird with a crest. The females are grey, the males are a dramatic black with white wing tips and red eyes. Silky-flycatchers nest in desert mistletoe, which attracts insects when it flowers. The birds eat the insects and feed them to their young; the rest of the year they live off the berries.

“And the berries have a very sticky substance in them,” says Esque. “And it will pass through the bird and wherever the bird defecates it’ll stick to a branch, and if it’s a live branch there’s a possibility that the mistletoe will grow there.”

Mistletoe shrubs. (Photo: tmv media/flickr)

Spotted owls, hawks, doves, chickadees, grouse and many other birds also nest in mistletoe.

In the winter, when food is scarce, mistletoe berries feed migratory birds such as robins and bluebirds. In North America, a butterfly called the “great purple hairstreak” drinks mistletoe nectar, mates in the mistletoe canopy, and lays its eggs on mistletoe so that caterpillars can make a meal of it once they hatch. In Mexico, mistletoe with brilliant flowers attracts hummingbirds. In South America, an adorable mouse-like marsupial called a Monito del monte munches on mistletoe fruit and distributes its seeds throughout the dense forests of Chile and Argentina.

If poop doesn’t get the job done, mistletoe gets proactive. The plant is one of several that boasts explosive seeds—forcefully ejecting them from the berry and shooting them up to 50 feet at speeds up to 60 miles per hour in an attempt to splatter nearby trees and shrubs.

There’s another group besides birds and other fauna that some think could benefit from mistletoe: Cancer patients. Mistletoe extract has a long history as a holistic cancer treatment, particularly in Europe. In the United States, the Federal Drug Administration has not approved the medicinal use of mistletoe, but some institutions are warming to the idea. In 2014, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine initiated a clinical study into its effectiveness after a cancer survivor formed a nonprofit to fund the research.

Berries on the Phoradendron californicum, Desert Mistletoe, which is also a hemiparasite. (Photo: Robb Hannawacker/flickr)

Channing Paller, an assistant professor of oncology at the School of Medicine and study leader, told John Hopkins Magazine that mistletoe could potentially help boost the immune system.

“In the past, doctors may have wondered if they were giving their patients snake oil,” Paller told the magazine. “But I think people are becoming a little more open-minded.”

In England, mistletoe is cultivated commercially, particularly in apple orchards. It’s a trend that never caught on in the U.S., where people still harvest mistletoe in the wild.

“It’s pretty hard work, I tried it once,” says Esque.

It was an experiment that he didn’t repeat; a full day of shimmying up trees produced a garbage bag’s worth of bounty that Esque sold for about $50. “You’d probably spend half that on gas,” he points out.

Mistletoe attached to an apple tree in England. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But he still likes to keep sprigs of the plant around his home during the holidays. Pine boughs and other holiday greens help bring an increasingly urbanized world closer to the natural one.

“Bringing nature into your house is a nice thing, and I enjoy it,” says Esque. Even if you aren’t smooching underneath it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook