These Tiny Jewels Come From One of Alaska’s Most Unusual Beaches

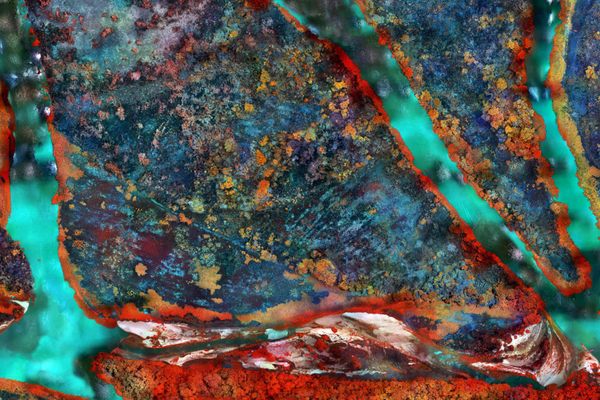

This microscopic treasure was collected from a remote site near the Arctic Circle.

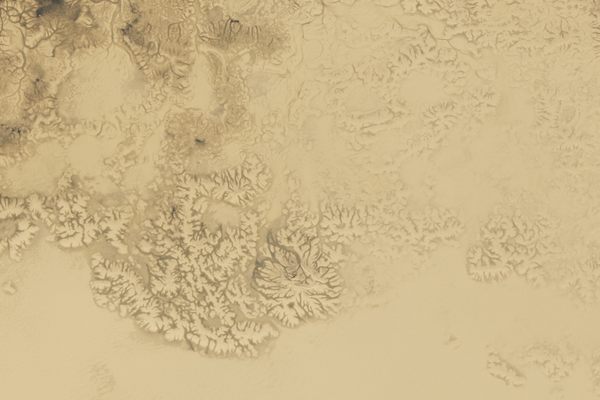

Just shy of the Arctic Circle, where Alaska’s Seward Peninsula stretches westward toward Russia, there is a most improbable sliver of land. Point Spencer sits at the northern tip of a miles-long, narrow spit of sand, gravel, and permafrost that’s less than 100 feet wide in places. To the east is Port Clarence Bay, where depths can exceed 40 feet—an anomaly amid the region’s shallow coastal waters. To the west is the wild and unforgiving Bering Sea, home to winter storms that regularly churn out waves 45 feet or taller.

In between, the site that is now Point Spencer has, at various times, been hundreds of miles inland or completely inundated by the sea. It has witnessed waves of human dispersal over millennia, and served as both an intercontinental marketplace and a Cold War military outpost. Now, as another chapter for Point Spencer begins, it can be seen in a dazzling way: Magnified 10 times, sand originally collected from one of its beaches appears as glittering, semiprecious stones.

The jewel-like particles represent a wide range of minerals, including moss-green olivine, blue-green glauconite, and iron-rich, orange-colored quartz. The variation speaks to how Point Spencer formed—at least, in its most recent incarnation.

For millennia, the spot that’s now Point Spencer was more than 500 miles inland, at roughly the center of Beringia, a landmass that connected Asia and North America during the last Ice Age. The first humans arrived to the Americas via this corridor, both on land and by following the coast. As the climate warmed, ice sheets melted and rising seawater inundated Beringia. The area around Point Spencer was one of the last spots left high and dry, and only sank beneath the waves about 6,000 years ago.

As the modern coastline took shape, glacial meltwater flowed into the sea via Imuruk Basin and an estuary to the east. Like most of Alaska, the Seward Peninsula is geologically complex, and the water collecting in the basin carried a variety of material, each with its own mineral composition: volcanic rock from an ancient lava field to the north, silty sediment washed in from the tundra, and even specks of gold from the Kigluaik Mountains to the south. Currents, whipping in a hook-like shape beyond the estuary, deposited the disparate bits of rock, sand, and organic matter along a curve between the Seward Peninsula and open sea, creating the spit over time, and keeping Port Clarence Bay free of silt and other sediment.

The Iñupiat people used the Point Spencer area for centuries as a meeting place for trade between groups on both sides of the Bering Strait, and as a staging area for hunting seals and whales. Human remains found on the spit by archaeologists a decade ago, and repatriated in 2021, may be 300 to 600 years old. The spit was not an easy place to live: On at least one occasion, in 1912, as skies blackened with ash from the powerful Novarupta eruption about 600 miles away on the Alaska Peninsula, a storm surge submerged the entire spit.

In the mid-20th century, the strategic combination of proximity to the Bering Strait and presence of a deepwater bay attracted the U.S. military. The Coast Guard established a long-range radio navigation station at the northern end of the spit for half a century. Its 1,350-foot radio tower was, for decades, the tallest structure in Alaska.

The tower was dismantled when the Port Clarence station closed in 2010. In 2020, ownership of the 2,000-plus acres was transferred to the Iñupiat-administered Bering Straits Native Corporation. Now, as dwindling sea ice opens new ship routes and countries clamor for influence in a warming Arctic, Point Spencer is poised for a new chapter. Potential plans for future development include a scientific research station and a new port. Whatever shape the spit’s future takes, the waves lapping its beaches will continue to leave behind an array of tiny jewels.

Alaskan Sand, taken by Xinpei Zhang, was recently named as an Image of Distinction in the Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook