Mark Twain Had a Lifelong Feud with the United States Postal Service

What made the celebrated author hate the mail service so much?

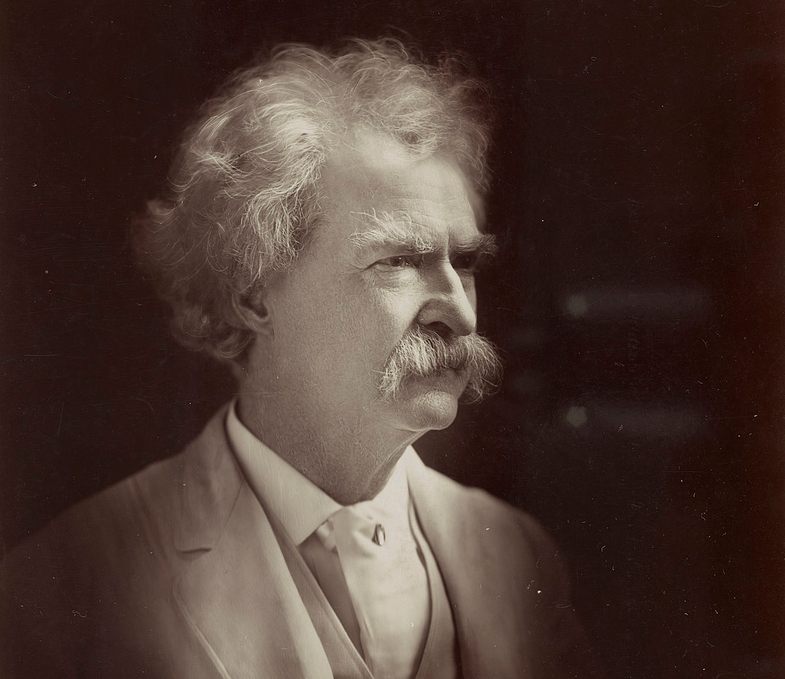

Mark Twain, pictured in 1907. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ds-05448)

When it came to speaking his mind, Mark Twain was rarely one to pull punches. Twain was often critical of others, whether it was calling President Theodore Roosevelt a “bully” or pillorying the writings of Jane Austen (“Every time I read Pride and Prejudice I want to dig her up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone,” said Twain in a 1908 letter.) However, Twain’s most heated rivalry was not with another author or president but rather an entire branch of government: the postal service of the United States.

Twain’s opposition to the post office spanned several decades, with the acclaimed author making many of his gripes public. He published newspaper articles with harsh criticisms of new regulations, publicly feuded with members of the service, and even scored a meeting with Britain’s Postmaster General in an effort to makes overseas shipments more affordable.

The creator of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn put nearly as much effort into his battles with the postal service as he did into his storied works. So what was it about the post office that made this man of letters clash with a service that conveyed letters?

A crowd waits in a Post Office, c. 1890. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-89496)

If prompted, most people could come up with valid complaints about the post office, but few have harbored a resentment toward it quite like Twain. During a short-lived position in the office of Nevada senator William Stewart in 1867, he even tried to prevent new ones from being built. When the senator received a request for a post office in a Nevada mining camp, Twain took the liberty of responding, stating that there was no need for a post office, and offered a new jail instead.

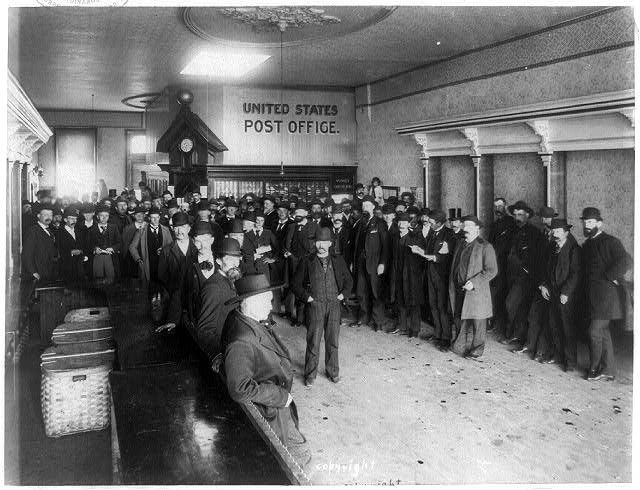

Twain often shared his frustrations about the post office in editorials for local newspapers, with particular ire reserved for Postmaster General David M. Key, a senator who served in the role from 1877 until 1880. Key’s new, stricter regulations on mailing letters and packages infuriated Twain to no end. In an 1879 letter to the Hartford Courant, Twain expressed discontent at Key’s most recent addition to the postal regulations, which required envelope addresses to be more specific (addresses before were not required to list streets or states, often times a name and city would suffice).

Twain complained that these new regulations were a waste of ink, time, and money for all citizens. “Isn’t it odd that we should take a spasm, every now and then,” Twain remarks, “and go spinning back into the dark ages once more, after having put in a world of time and money and work toiling up into the high lights of modern progress?”

David Key, the Postmaster General, c. 1860s. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-cwpbh-04495)

Twain’s editorial prompted a response from Thomas Kirby, the private secretary to the Postmaster General, who tried to explain that the new regulations were created with good reason. Twain had Kirby’s letter published in the Hartford Courant with his response attached, which accosted Kirby for “meddling” in affairs that did not concern him.

“You seem to think you have been called to account,” Twain opens. “This is a grave error. It is the Post Office Department of the United States of America which has been called to account.” Twain lambasts Kirby for several paragraphs, going on to refer to the Post Office as “the dog” and Kirby as “the tail” and states that Kirby “endeavored to wag the dog” when he should instead be waiting for “the dog to wag you.”

However, Twain was not piqued by all post office workers and rules. When a letter announcing Twain’s election to the New York Press Club was mailed without the proper postage, a postmaster named James paid the postage himself and forwarded the letter, which included a party invitation, to Twain. Unfortunately, Twain was unable to make the reception, but sent a response explaining the mishap, and complimenting James.

A post box in 1911. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-hec-00561)

Twain wrote, to the New York Press Club: “Had your unpaid letter passed through the average Post Office of the land I should have received my invitation about three months from now through the Dead-letter Department, after much correspondence [&] ruinous outlay of postage. I [wish] that there were more Postmaster Jameses in the land.”

Of course, Twain also took offense to the use of a Dead Letter Office, where some 30,000 daily letter and parcels that could not be delivered for failures of handwriting, postage, or other reasons ended up, in Washington D.C. In an 1876 letter to the Saturday Evening Post, he gripes about how a letter sent to him was one penny short on payment, forcing it to be sent to the Dead Letter Office.

The post office mailed a request for the missing penny, and when Twain sent the payment (through a mailed envelope, tacking on another three cents) and received the letter, he was saddened to discover it was only a doctor’s bill. The sardonic author sent his letter to the Post covered in stamps “amounting to thirty-nine cents, when three cents would doubtless have answered every purpose,” states an editor’s note.

Mark Twain writing in his study, c. 1870s. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

He didn’t just criticize it; Twain actively tried to improve the mail service himself. The author once pitched his invention of a “postal check” to the service, a sort of pre-paid, mailable money order that could be cashed at a post office and used to purchase items. Twain prepared a lengthy pitch, which included a scripted dialogue of a “Wisdom Seeker” explaining the check to a “Statesman.” A bill regarding a postal check reached Congress but was never adopted.

Twain even considered taking the position of postmaster in San Francisco, he revealed in an 1868 letter to Elisha Bliss, then the president of the American Publishing Company. The author had received the support of a number of high-ranking officials in the city, where he was then living, but bowed out when he realized it was too strenuous a job to be able to work and write simultaneously.

One has to wonder if the acceptance of the position would have remedied Twain’s discontent for the postal service or exaggerated it. Maybe a shifted point of view would have changed Twain’s opinion on the department entirely.

The Mark Twain commemorative stamp being unveiled in 2011. (Photo: Dannel Malloy/CC BY 2.0)

In 1907, Twain complained of the high cost to send a letter to England, stating that the established price of one dollar per pound of letters was “downright robbery.” Twain even organized a meeting with the British Postmaster General on the subject, which he labeled “petty larceny,” where he proposed that mailing letters between England and America should only be a penny each way, stating that the lower price would increase the number of letters sent, and would result in higher revenue for the postal service. Needless to say, his proposal was not adopted.

Twain had strong feelings about the requirement of stamps on letters, too. “When England in 1848 invented stamps,” Twain remarked before his meeting with the British Postmaster General, “my feelings were decidedly anti-English.” Twain saw stamps as an inconvenience and stated that his letters “arrived all the same” without them.

Ironically, the USPS released a commemorative stamp depicting Twain in 2011, meant to honor his legacy as a hero of American literature. Twain would surely be furious at the idea of a “forever” stamp that only worked domestically. If he wanted to send a complaint to England, he’d have to add two more.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook