A Once-Lost Dress from ‘The Wizard of Oz’ Goes to Auction—Maybe

Dorothy wore the disputed blue-and-white frock when she faced down the Wicked Witch.

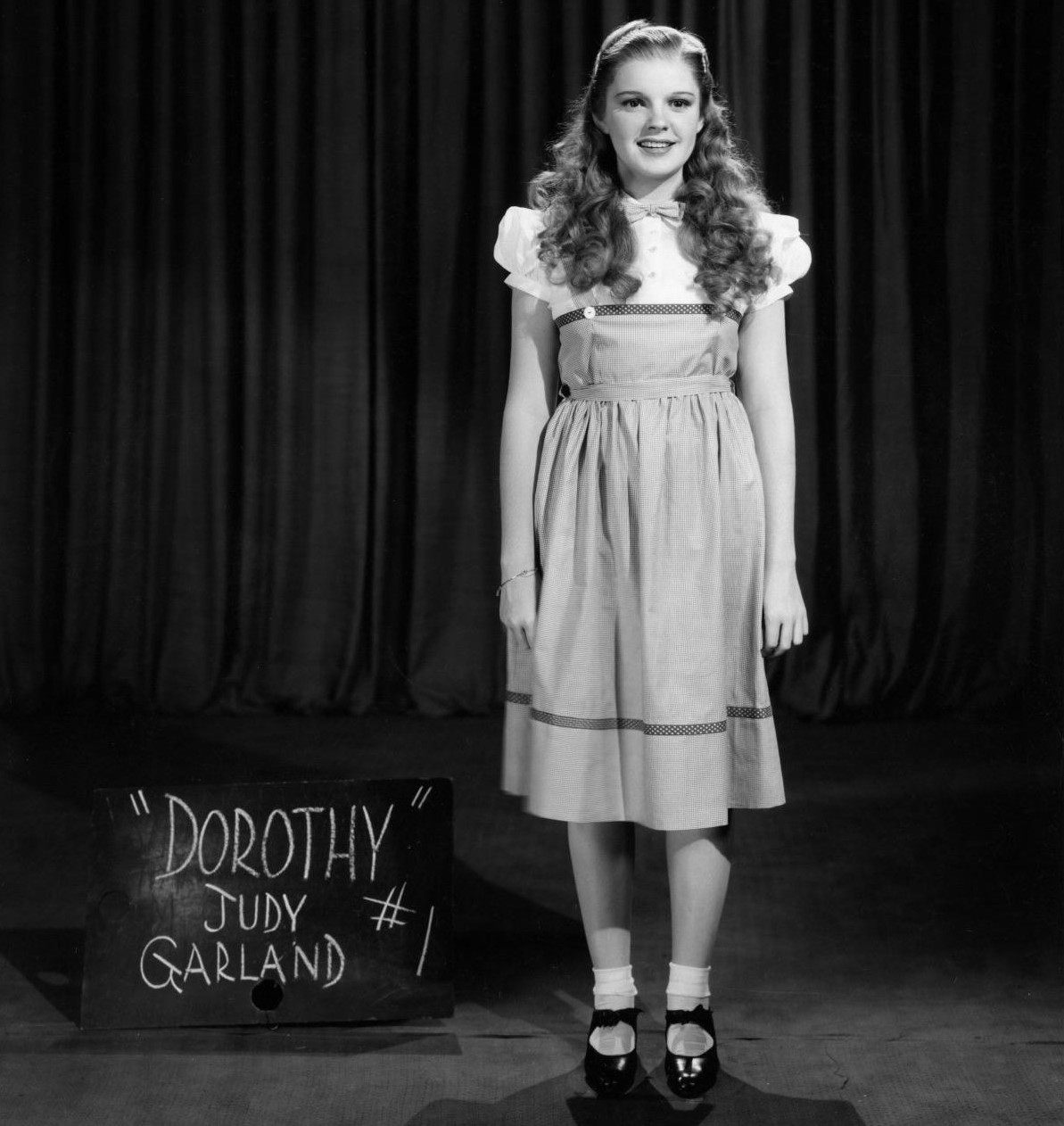

In December 1938, 16-year-old Judy Garland waited on the set of The Wizard of Oz, trying hard not to wrinkle her blue-and-white gingham dress. The scene they were filming that day—the moment where young Dorothy faces the Wicked Witch of the West would become one of the movie’s most iconic and so would the ensemble Garland wore in the film. Today, one pair of her ruby slippers is on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. But the dress Garland wore in that pivotal scene was not so well preserved. After filming wrapped on the picture, the dress changed hands several times before vanishing entirely for almost 50 years. Just like in The Wizard of Oz, the dress had to embark down its own detour-ridden yellow brick road before being recently listed for auction at Bonhams—a journey that seems far from over in light of a new lawsuit contesting the dress’s ownership.

If the auction moves forward as scheduled, the recovered “Dorothy” dress is expected to garner between $800,000 and $1.2 million at the Bonhams Classic Hollywood: Film and Television sale in Los Angeles on May 24. According to Helen Hall, Bonham’s director of popular culture, this is only the second Dorothy dress found that includes the white blouse Garland wore beneath the blue-and-white frock and is one of just four of the gingham dresses known to exist. And yes, the dress has the small secret pocket where Dorothy would have hidden a handkerchief to wipe the tears from the Cowardly Lion’s eyes. “People always ask about the secret pocket,” Hall says.

While it’s impossible today to imagine Dorothy walking the yellow brick road in anything but blue-and-white gingham, costume designer Adrian Adolph Greenberg designed somewhere between eight to ten different “test dresses” for the film, says Wizard of Oz historian and author John Fricke. The final dress was very simple, almost exactly the garment “with checks of white and blue” described in L. Frank Baum’s 1900 book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz on which the film was based.

After the design was finally approved, Adrian got to work making multiples. “When the movie came out in 1939, the publicity said that Judy went through ten of those dresses through the course of the filming. That was probably an elaboration, but I don’t think it’s any question that there were maybe four or five or even six of them,” says Fricke. Some of those dresses have come up for auction before, including one “sweat-stained” dress sold by Bonhams in 2015 for $1.5 million. But this new dress is one of the few that’s been pinpointed to a specific scene from the film.

“I stared and stared and stared at the dress,” says Hall. She was looking for anything that would distinguish this dress from the others used in the film. Finally, Hall spotted an uneven line of gingham near the top of the bodice. “I watched the film frame by frame by frame.” And there, in the scene in the witch’s castle was that distinctive uneven row of checks. That the dress was not only used in the film but was used in one of its most climactic scenes is of great interest to collectors, says Hall.

Interest in Oz and film memorabilia has only taken off in recent decades. After filming wrapped on The Wizard of Oz in 1939, this dress, along with Dorothy’s other dresses, was tucked away in the Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM) Studios’ archives, where it sat untouched for years. Eventually, the dress made its way into the hands of Academy Award-winning actor Mercedes McCambridge, maybe at the star-studded first-ever MGM auction of film memorabilia in 1970 (an event that jump-started the sale of such artifacts) or perhaps from the archives directly. “We don’t actually know how she got it,” says Hall.

What is known is that in 1973, McCambridge gave the dress to the Catholic University of America’s charismatic Gilbert “Gib” Hartke, the “show-biz” priest and acting teacher who founded the university’s drama school. At the time, McCambridge was an artist in residence at the drama department, which had grown into one of the top acting programs in the country under Hartke, training actors like Susan Sarandon and John Voight. But sometime after Hartke’s retirement the following year, the dress went missing.

Over the next five decades, many started to believe the dress was nothing more than “an old wives’ tale,” says Jacqueline Leary-Warsaw, dean of the university’s Benjamin T. Rome School of Music, Drama, and Art. “People had for a long time started to believe that it really didn’t exist.” One faculty member even told Leary-Warsaw that the dress was something like a ghost haunting the school. But then, sometime in 2021, a retiring faculty member found an unassuming shoebox in a white trash bag as he was clearing out his office. He scrawled a note that read, “look what I found,” and then left the shoebox on top of a cabinet in the school’s theater wing. Several months later in July 2021, as the university prepared to renovate the Hartke Theatre, the shoebox was again found, with Judy Garland’s Dorothy dress and blouse tucked safely inside.

The university decided to sell its find and use the proceeds to endow a faculty chair to develop a new film acting program at the school. But on May 4, Barbara Hartke, Father Hartke’s niece, filed a lawsuit claiming that the dress actually belongs to her; her uncle passed away in 1986. Barbara Hartke’s filing argues that McCambridge “specifically and publicly” gifted the dress to Hartke making the dress “an asset of the descendant’s estate” and seeks to stop the auction. (Her lawyer could not be reached for comment.) Speaking before the lawsuit was filed, Leary-Warsaw said that the dress was given, “not only as a thank you but with the idea that the dress would someday be used to fund the department for its initiatives.”

Beyond any looming legal battles, one thing remains clear—everyone wants to be close to this piece of film history. Just last week, social media platforms were flooded with pictures of people posing with the Dorothy dress when it was on display at Bonhams in New York City. “That movie and [Judy Garland’s] performance just resonate,” says Fricke, “and in this day and age it’s a lovely thing that something that is that pure in terms of entertainment has had this kind of longevity.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook