Following the Mysterious Trail of Europe’s Last Wild Lions

Researchers use art and ancient bones to make the case for modern lions once freely roaming Southeastern Europe.

This story was originally published on SAPIENS and appears here with permission.

Once upon a time, people near the valley of Nemea in southern Greece lived in mortal fear of a lion lurking in the surrounding hills and preying on the populace. Only mighty Hercules, challenged by the king of nearby Tiryns, could slay the beast.

The son of Zeus cornered the powerful carnivore in a cave and choked it to death with his bare arms. Thereafter, the people lived in peace, and Hercules continued his famed adventures.

Of course, the Nemean lion story is a mere fable, part of an eclectic cast of gods, heroes, and fantastic beasts that populated the myths of antiquity. There are certainly no wild lions in Europe today.

But early 20th-century archaeologists in mainland Greece thought that there might be some truth to the existence of lions in the region in ancient times. Why else do these creatures feature so prominently—and realistically—in art from the late Bronze Age, as well as myths and actual reports by later scholars from the Classical period, such as Aristotle and Herodotus?

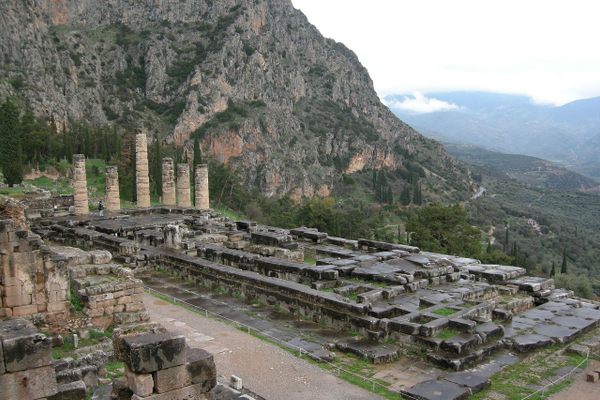

Though such theories were long dismissed by other researchers, in 1978, two prominent German zooarchaeologists made a startling discovery. During an excavation of Tiryns—the same city whose legendary king dared Hercules into action—they chanced upon a feline heel bone near a human skeleton. It was unmistakably from a lion, they concluded, and possibly of the same species that inhabits parts of the African continent today.

The bone was only the first of dozens to surface in Tiryns and elsewhere over the following decades. Though some details remain unclear, many archaeologists and historians now use this evidence to conclude that modern lions once lived alongside people in parts of what is today Europe, including Greece, for hundreds of years. Today lion bones offer a rare glimpse into the Bronze Age world and the fraught relationship humans had with these fierce predators, animals that inspired legends and creative works for centuries.

“Now it’s possible to say that some [lion images] could have been recalled from real experiences on the [Greek] mainland,” says art historian Nancy Thomas. The finds, she adds, cast “a whole different light on the art … and how hunting real lions could have played into the elite structure development that was going on in Greece at the time.”

Thomas has been a believer that wild lions existed in Bronze Age Greece since before any bones were found. A professor emerita at Jacksonville University in Florida, she has shoulder-length, reddish curly hair and an animated smile whenever she talks about lions. Many in the field point to Thomas as the expert on the wild lions of Greece.

Her ideas about these felines first developed during her dissertation work in 1970, for which she carefully studied Bronze Age depictions of lions engraved on seal stones, plaques, and other objects. Around 1700 or 1600 B.C., the carnivores had become a popular emblem of the Mycenaeans, a society on the Greek mainland known for its military prowess and a hierarchical political network governed by a palace-dwelling elite. (Tiryns was a military and cultural hub of Mycenaean society.)

What struck Thomas was that although many depictions showed generic, cookie-cutter lions, easily based on imagery from elsewhere, a few of them looked strikingly real—not just in their lifelike features but also in their behavior. “They look so fabulous,” Thomas says. “I always had this feeling that some of those lion scenes look too real to have been just copied.”

For example, gold plaques, seal stones, and tombstones found in the graves of wealthy people at Mycenae—another major Mycenaean center—featured lions lunging after deer, people, and livestock. On a decorated dagger, a lion, glistening in gold against the dark metal of the blade, assails four men armed with spears and bows, while two lions flee the scene.

Around the same time that Thomas was analyzing these images, the study of animal bones at ancient sites was taking off, and two zooarchaeological pioneers, Joachim Boessneck and Angela von den Driesch, uncovered the lion heel bone at Tiryns. This bone wasn’t proof of a wild lion; any bones of the feet, claws, or teeth could have come to Greece as souvenirs from the Middle East or dangling on pelts.

But then the pair found four leg bone fragments and a rib piece associated with different time periods between 1700–1600 B.C. and around 1200 B.C. These discoveries “made the [whole] excavation … worthwhile,” they wrote in 1990.

While Boessneck and von den Driesch concluded that the bones were evidence of wild lions in the area, other scholars had doubts. “For years, I would not buy it,” says John Younger, an archaeologist at the University of Kansas and a friend of Thomas. “I would state this publicly.”

Younger believed the leg bones—still few in number—could come from the remains of pet lions or traded souvenirs rather than wild individuals. He also noted that the archaeological record simply didn’t offer much evidence of European lion bones from outside of Greece or earlier times. Without such finds, the idea of imported animals (or their remains) made more sense than the notion that wild lions had journeyed into Greece and become established.

Furthermore, the artistic depictions of lions might simply be based on imagery from elsewhere. Younger had studied seals and rings from the Greek Bronze Age, which, he had determined, came from the Greek island of Crete. Home to the older Minoan civilization, the isle’s artisans likely copied many lion motifs from Egypt and the Middle East. Nonetheless, Thomas believed zooarchaeological work could offer more answers. She started corresponding with von den Driesch to learn more about ongoing excavations. In 1998, something came in the mail for Thomas that would address the skeptics’ critiques.

It was an inch-thick dissertation from one of von den Driesch’s students, Henriette Manhart, who had compiled ancient bone records from Bulgaria and its neighbors. Among them were numerous lion bones from 13 sites. Evidently, modern lions—the same species that roams the savanna in parts of Africa today—had a history in Europe.

“I had no idea that what I would find would be so extensive,” Thomas recalls. “That was really like a lightning bolt to me.”

In the years to follow, zooarchaeologists continued to make lion finds in Europe. In addition to teeth and toe bones, Manhart and others have documented pelvis fragments, leg bones, and vertebrae from sites across Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and southern Ukraine.

Many bones date back to more than 1,000 years before the Bronze Age began in Greece, in a period in Southeastern Europe known as the Copper Age. Among the most remarkable caches was a collection from an ancient hunting site near the small village of Durankulak by the Black Sea coast in northeastern Bulgaria: 10 lion bones from jaws, legs, and shoulders, likely from two adults and a juvenile that lived around 4000 B.C.

Unlike isolated finds of claws, teeth, or foot bones, this range of remains suggested a source that wasn’t simply imported souvenirs or pelts. Instead, a relatively even representation of the entire skeleton makes for strong evidence of wild lion populations, says László Bartosiewicz, a zooarchaeologist at Stockholm University. “I think that it is quite convincing; I really believe that there were lions. So many bones couldn’t have been imported.”

The bones are most certainly from a modern type of Panthera leo, experts say. (Although they disagree over the subspecies.) The only other lion species known to occur in Europe—the cave lion, sometimes classified as Panthera leo spelaea—died out some 6,000 years before the animals unearthed in Southeastern Europe.

The fossil record suggests that modern Panthera leo populations were once widespread, stretching from parts of Africa through the Middle East to India. But the route these cats would have taken to reach Europe, whether across the mainland or crossing the Bosporus over an ancient land bridge, remains a mystery.

Scholars such as Bartosiewicz speculate that lions ventured around the Black Sea into Ukraine, then moved south to the Balkans. From there, some could have roamed farther south to Greece.

Thomas, who has now spent years asking excavators for new evidence and compiling archaeological reports published in various European languages, has even converted some of the skeptics. By 2012, she had identified 25 sites in Southeastern Europe and 13 in Greece. In December of that year, scholars of Bronze Age Greece flocked to Paris for the 14th Aegean Conference, where Thomas presented her research, including descriptions of bones found across Southeastern Europe, along with artistic and historical accounts of lions.

The full tally of bones was a little more than 100, 41 of them from Greece. Representing just dozens of individuals, the lion population was probably quite small in Southeastern Europe. But to Younger, who was sitting in the audience, the number and variety was too large to be easily accounted for by live lions imported as pets or for other purposes. He stood up. “I’ve resisted you for years, but I’m absolutely convinced now,” he recalls telling Thomas.

“The way she presented it, you go, ‘This is not accidental. This means something,’” Younger says. “It’s not, in a sense, the quantity as it is the consistency of finding a lion bone here, a lion bone there … over a period of a couple of hundred years.”

Today, thanks to scholarship by Thomas, Bartosiewicz, and many others, most researchers agree that lions were present in Southeastern Europe’s Copper and Bronze ages. But some doubts still linger over whether these big cats roamed freely in Greece specifically.

For instance, Paul Halstead, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Sheffield in the U.K., thinks it would have been difficult for wild lions to have established themselves in the Peloponnese—the southern peninsula that houses Tiryns and Mycenae—given its small size and narrow connection to the rest of Greece.

It’s impossible to rule out that some wealthy Bronze Age Greeks imported lions for hunting parks or menageries. Mesopotamian kings were known to do so with lions and other exotic creatures around that time, notes archaeologist and art historian Marie Nicole Pareja, of Dickinson College.

Still, the bone count continues ticking upward—Thomas has recorded 110 to date—strengthening her case. In addition, the discovery of remains in relatively obscure locations far from major trading routes, such as the small, fortified Peloponnesian settlement of Aigeira, in what is now northwestern Greece, is hard to explain away as an exotic animal import.

Gerhard Forstenpointner, a now-retired professor of veterinary anatomy who has excavated in Aigeira, recently found a lion hipbone dated to around 3000 B.C. in the early Bronze Age, as well as a cervical vertebra from a lion cub that lived around 1300 B.C.

“This is no trophy. This is just the bone of a poor dead young lion,” Forstenpointner says, noting there is no reason to import cubs. “In my eyes, those [bones] are proof for a local, persisting population of lions.”

Meanwhile, scholars are considering the interactions Europe’s wild lions had with humans. Younger, for example, feels the presence of these predators helps explain the cultural emphasis in Bronze Age Greece to “fight for your place in the sun.”

It’s probable, Bartosiewicz says, that lions “were getting in people’s way,” going after livestock or humans. In this respect, they were not dissimilar from other large predators in Europe, like wolves and bears, whose populations were decimated by people.

Cut marks on bones from Southeastern Europe suggest humans skinned or butchered the animals for pelts, meat, or even symbolic rituals. Bartosiewicz and Forstenpointner think it’s likely that people consumed lion flesh—adding credence to the legendary tales of Achilles, who is said to have feasted on lion entrails as a child.

It would have taken multiple people plus a lot of courage, skill, and good weaponry “to even think about challenging [lions],” says Andrew Shapland, a curator at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University.

For Mycenaean warriors of the day, hunting and eating lions may have become a prestige activity, a means to demonstrate wealth and power. For instance, Forstenpointner found a lion foreleg bone in what was once a wealthy Bronze Age settlement on the island of Aegina, south of Athens, which may have been the tasty spoil of a hunting trip to the mainland. Minoans and their artists, too, could have sailed over from Crete to take part in the lion hunt, Shapland has suggested, leading to their lifelike lion illustrations.

Eventually, people won their war against Panthera leo—a fate that befell these animals throughout much of their range, save pockets of the African continent and India. It’s clear, says zoologist Marco Masseti, of the University of Florence, that European lions died out in antiquity, in conflict with humans. “Even in these times, Europe was already a crowded place,” he observes.

In Southeastern Europe, including Greece, the most recent records of lion bones are from around the seventh century B.C. While Younger puts the Greek lion’s disappearance from the wild sometime around 1200 B.C., when artistic depictions of lions become less ferocious, less accurate, and more like “really trim deer.” Thomas suspects it’s possible that they survived into the Classical period, which some experts define as running between 500 and 300 B.C. That would be in line with historical accounts of rare, wild lions roaming northern Greece. Maybe the big cats really did attack the camels of Persian King Xerxes as he crossed Macedonia to invade Greece in 480 B.C., as Herodotus wrote.

Either way, the continent’s lions survived in art and story. Lions became a potent symbol of the animal kingdom at its most terrifying and inspiring. Their imagery, as shown on seal stones, daggers, and ivory plaques from Mycenaean Greece, would echo through later cultures and into modernity as people saw, reinterpreted, and reimagined these predators.

These beasts became larger than life, the stuff of legends. Archaeology has revealed that these animals were not just mythical creatures: Wild lions may have walked in Europe until quite recently, instilling fear, inspiring myths, and leaving behind a mystery for the ages.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook