Lionfish Kabobs: Teaching Old Sharks New Tastes

Photo by Jens Petersen via Wikimedia

Photo by Jens Petersen via Wikimedia

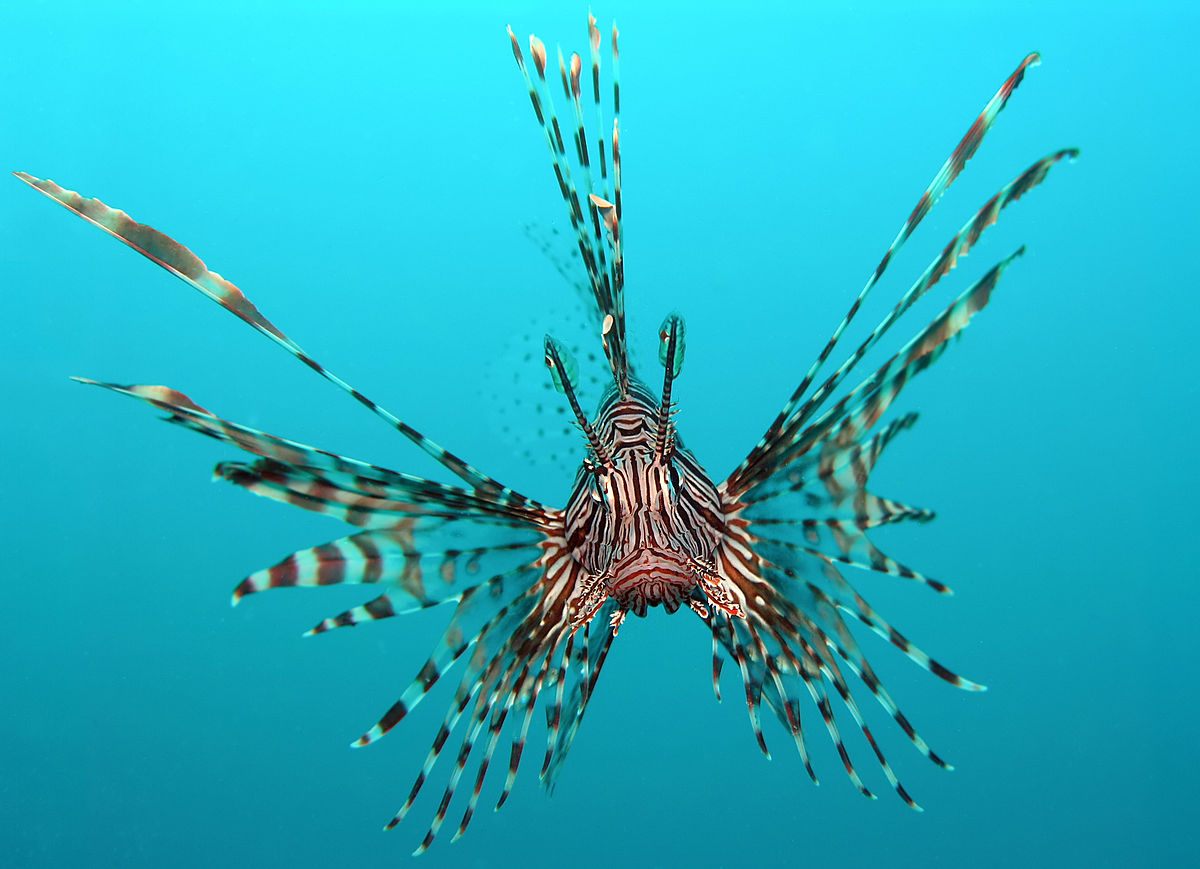

Lionfish, though stunning creatures, are very, very dangerous to marine life, given their venomous spines, sophisticated hunting techniques, and extremely high reproduction rate (a mature female can produce up to 2 million eggs per year). Though native to the Pacific and Indian Oceans, in the 1980s the aquarium trade brought these creatures into the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, where they have no natural predators. As Lionfish are also voracious and wide-ranging eaters, they have been decimating their surrounding reef life ever since. They are now considered an extremely invasive species, and it has been suggested that they are poised to become the most disastrous marine invasion in history.

Scientists and conservationists are trying many different tactics to curb the lionfish population. In Roatan Marine Park, Honduras, efforts have been made to convince people to eat the fish themselves — they are said to be delicious once the venomous spine is removed. Although spears and harpoons are illegal in Honduras, the park has also gotten special government approval to give local divers licenses to hunt lionfish with fishing spears, even sponsoring contests to see who can kill the most in a day.

photo by Judy Baxter via Flickr

photo by Judy Baxter via Flickr

Over in Cuba, Jardines de la Riena National Marine Park dive operations manager Andrés Jiménez has been trying a different tack: Since 2010 he has been working on coaxing reef sharks into eat the exotic lionfish, since they are among the only potential predators not affected by the venom in its spine. Somewhat gruesomely, Jiménez skewers the fish onto a spear like a kabob, then brings the struggling creatures over to the sharks, who gobble them up.

The goal is to train the sharks to prey on the lionfish of their own volition, which some say is working. Antonio Busiello, a marine photographer who has documented the attempts, witnessed sharks hunting lionfish shortly after the spoon-feeding attempts. But others, like marine ecologist Serena Hackerott at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, believe that this plan could definitely backfire if the sharks begin to associate divers with an easy snack. Ian Drysdale, who coordinates the Healthy Reefs Initiative in Honduras, also believes this method could lead to problems. “You don’t want to relate human divers with shark feed,” he told the Washington Post. “It can get out of hand.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook