Dracula’s Chamber: The Dark Legend of Buda Castle Labyrinth

Gargoyle under Budapest (via Labirintus)

Gargoyle under Budapest (via Labirintus)

Carrying only a gas lamp, at the heart of the Buda Castle Labyrinth there is nothing except for slimy damp walls, darkness, and things that go bump in the night. After 6 pm it’s lights out in Labirintus, and each group gets a single lantern to navigate around the network of natural tunnels found in the underbelly of Budapest’s Castle Hill.

I hear a sequence of squishes as my feet leave an impression in the muddy path, and I can smell smoke. I’m a good few metres underground, there shouldn’t be any smoke here, except for the flame leaping up inside the metal canister hanging off my wrist, but the smell is different. I can hear an echo of voices behind bounding off the stone walls carrying up from different tunnels.

I hold the lamp up, the warm red flame licks the walls and I hear an uncomfortable hum in the background. Some sinister music plays quietly, but becomes louder with each step. The air feels heavier, and there is a haze of smoke lingering. I hear screams in the distance, either from others in the tunnel or as part of the eerie soundtrack being pumped in. The light illuminates fragments, bits of rubble with an Ottoman slant to them, a stone turban perhaps from a disembodied statue, and a placard on the wall with a picture of the infamous Vlad Dracul.

Above the portrait, words inscribed in gothic script say “Dracula’s Chamber” in both Hungarian and English. I know nothing is going to jump out at me, but I still hesitate to venture further into the dark, smoke clad chambers alone, and decide to wait for a few Australian tourists I left behind a few rooms back.

Inside the labyrinth (photograph by Jerzy Kociatkiewicz/Flickr)

Inside the labyrinth (photograph by Jerzy Kociatkiewicz/Flickr)

The labyrinthine network of tunnels under Buda Castle arose from the hot thermal waters coursing through the subterranean underbelly of today’s Budapest. Archaeological evidence points to inhabitants living down the caves from pre-history right up to the Middle Ages, but apart from offering shelter, these caves hold a darker history in the years that followed.

A Turkish Harem once existed near the entrance to the labyrinth, and several female skeletons were found in the caves dating back to the era of the Ottoman occupation. Some believe that the women were thrown into wells when the Turks were forced out of the castle, but there is a more sinister legend behind the bones. One gruesome version of the tale is that the Pasha of Buda bricked up these women from his harem once he got bored of them.

The labyrinth also functioned as both a prison and as a torture chamber. In the 15th century, its darkest, dankest chambers held its most infamous resident — Vlad Tepes, better known to you and me as “Dracula.”

Dracula gargoyle in the labyrinth (photograph by Thomas Timlen/Flickr)

Dracula gargoyle in the labyrinth (photograph by Thomas Timlen/Flickr)

Vlad Tepes’s role as the Voivod of Havasalföld was to protect Christian Europe from the Ottoman invasion. However, conspiring to make deals with the Turks, the Hungarian King Matthias, his former ally, abducted and imprisoned Dracula in the bowels of the Castle Hill. The duration of Dracula’s stay in the subterranean chamber is uncertain. Some believe he was there over 10 years, others say it was for a shorter time, and whether or not he was tortured is a secret kept within the walls. However, after Dracula’s release, he became infamous for his impaling and torturous acts, clearly impacted by his time in prison.

On a placard down in the Labyrinth, one legend has it that Dracula died here and his body was buried in the Buda Labyrinth, his head elsewhere. It’s very likely just a spooky tale put in place to give tourists goosebumps. There are five legends about Vlad the Impaler’s death, and the exact date has never been pinpointed. One story says he was killed when he had sex with a Turk amidst the bodies of his loyal bodyguards. The true location of his burial is also a grey area, since the site said to be his resting place at Snagov, an island monastery just outside Bucharest with an “unmarked tombstone” attributed to Vlad Tepes, houses no human body — only bones and jaws belonging to horses.

However, in the 19th century, a ghost known as the “Black Count” terrorized the labyrinth, so could there be a connection? Or was he simply a man in a black cape having illicit liaisons down in the tunnels?

The figure of the Black Count has a root in history though, since there was once an impoverished count in the 1800s who allied himself with bandits, allowing them to hide out in the labyrinth in exchange for spoils. The story behind his life and death is unclear, but the stories of the mysterious black figure haunting the labyrinth still linger.

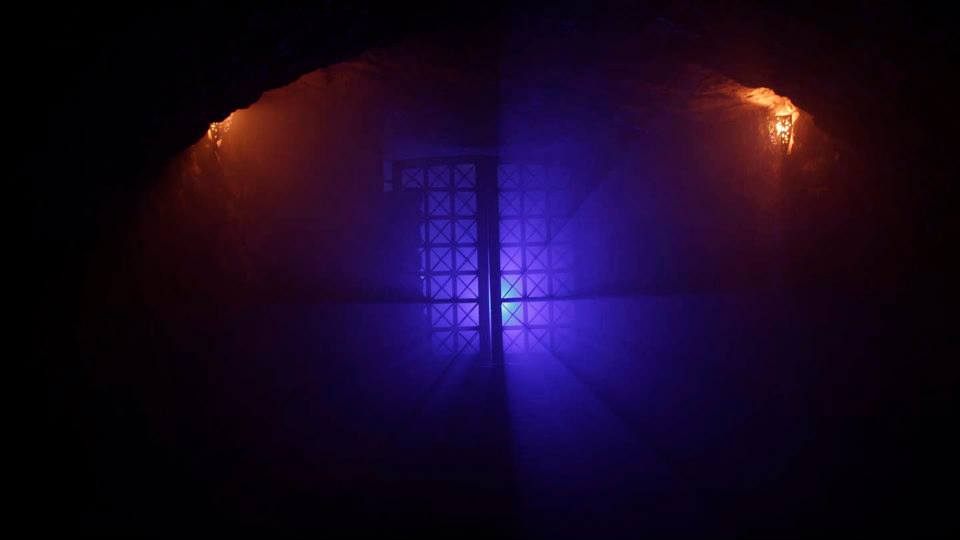

Illumination in the labyrinth (via Labirintus)

Illumination in the labyrinth (via Labirintus)

Finally mustering the courage to plough further into the labyrinth, the music deafened me, shaking the walls around the tunnel. The smoke cleared slightly as the shadow of a cross lingered under my lamp and I could make out a grave made out of plaster; behind a set of bars in the corner I caught sight of another chamber housing a coffin. I almost expected a bat to fly out and hit my head, but the spooky music just began again on a loop.

Even though the bowels of Buda Labyrinth has been turned into a hammy tourist attraction, these slimy, cold walls have certainly seen some horrors in their time. If ghosts existed they most certainly would roam down here.

via Labirintus

via Labirintus

via Labirintus

via Labirintus

via Labirintus

via Labirintus

photograph by the author

photograph by the author

All this month we’re celebrating 31 Days of Halloween with real tales of the macabre and strange. For even more, check out our spooky stories from 2011 and 2013.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook