Remembering Lilian Miller, the Pioneering Woodblock Artist Caught Between East and West

The many contradictions of a diplomat’s daughter who wanted all her work destroyed.

Artist and printmaker Lilian May Miller constructed her personal image as consciously as she did her artwork. When she was in Japan, she wore Western clothing, often favoring Amelia Earhart–esque ties and mannish blazers. On a 1929 lecture tour in America, on the other hand, at a time when Japanese women were casting off kimonos, she wore traditional Japanese dress. She cropped her hair short, went by Jack among family and friends, and described herself as unable to work up “even the ghost of” a romantic interest in men. To journalists, she explained that, as a child, she’d only spoken Japanese—almost certainly untrue, given that her parents were American. Contradiction and confusion all seemed to be part of the game.

Miller was born in Tokyo in 1895 to a diplomat father, Rainsford. Her mother, an English teacher, had come to Japan on a Christian mission. Rainsford Miller was an avowed Japanophile who spoke the language fluently and instilled in his daughters Lilian and Harriet, whom he called Jack and Hal, a particular interest in the local culture and language. This was unusual, says historian Katrina Gulliver, author of Modern Women in China and Japan: Gender and Global Modernity Between the Wars. “Some families in a similar situation would have simply sent her to boarding school back in America, and wouldn’t have encouraged her to have any particular relationship with Asian cultures.”

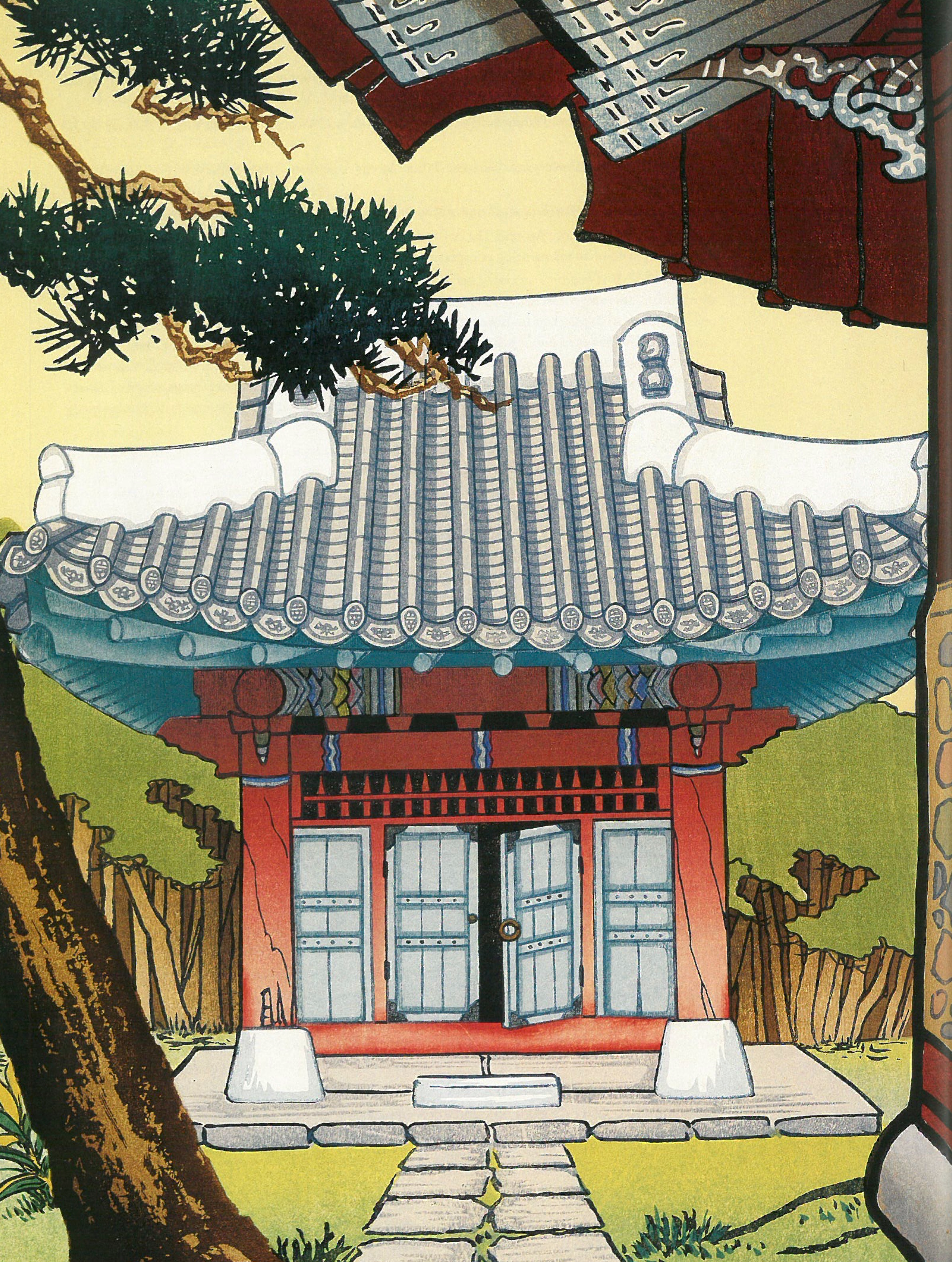

Miller went on to spend much of her adult life in Japan and Korea, with occasional stints on the West Coast or in Hawaii. In the United States she made a name for herself with her woodblock prints, cut with painstaking accuracy in a hyper-traditional Japanese style. This, and her extremely privileged background, made a her a notable figure. The 1942 Who’s Who in California describes her as: “Only Western artist to have had complete training in the classical Kano style of painting; studied in Japan, China and Korea; began at age of 9 under famous Court Painter to the Emperor Meiji; exhibited in Imperial Salon (Japan), at age of 12. One-man shows in all important cities of the Orient.”

From an early age, she was enrolled in a series of prestigious teaching ateliers, or juku, where she learned Japanese art techniques under strict traditional masters. After attending an American high school and then Vassar College, she returned to Tokyo as a young adult and resumed her artistic studies, eventually settling on woodblock printing as a preferred medium. In part, this was a financial decision—she could make more prints than drawings or watercolors. In general, Japanese art was, at the time, moving away from this traditional style, but she found a burgeoning market for this style of work in the wealthy expatriate community. In a 1932 Vassar alumni magazine, she wrote: “Today I try to work just as a Japanese would have worked a hundred years ago, with this difference: I have had to learn to be artist, cutter and printer all combined.” While Japanese artists worked in something resembling studio teams, Miller worked alone.

In so many aspects of her life, Miller was deeply unusual. She saw herself, she wrote, as “a messenger between east and west,” but acknowledged that it was a difficult position to be in. “Sometimes one falls in the gulf between.” Kendall Brown, author of Between Two Worlds: The Life and Art of Lilian May Miller, describes her unique position: “a Tokyo-born American who identified with the West when in Japan but with Japan when in America.” She was “a woman who strove for independence in a patriarchal society.” She was caught in “the friction between her desire to grow as a creative, modern artist, and the commercial expedient of producing attractive images of the East in naturalistic styles.” Her gender presentation was nonconforming and verged on androgynous—to her father, she referred to herself as “your boy Jack.” And, while she had male friends, her professional and personal lives featured women almost exclusively—from intense friendships with influential female reporters and curators, to lesbian romantic relationships, including a “brief but passionate affair” with her primary West Coast dealer, Grace Nicholson.

A question that plagues contemporary discussions of Miller’s work and presentation is to what extent they might today be thought of as Orientalist or appropriative. Her wearing of a kimono, for example, is a thorny topic. Gulliver describes it as “performance,” and notes that Miller only appears to have worn one when outside of Japan—to present as more Japanese. In her book, she writes, “Miller presents herself as a creature merely visiting from this ‘pure’ world [of Japan] through her Japanese attire.”

Today, the practice of white women wearing kimonos remains contentious. A 2015 exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts sparked protests when visitors were encouraged to try on a red uchikake kimono as part of a Claude Monet exhibition. Asian-American protesters deemed it racist “yellow face,” and called for it to be excised from the show. But, as the Japan Times wrote at the time, “the reaction to the exhibition from Japan—where the decline in popularity of the kimono as a form of dress is a national concern—was one of puzzlement and sadness. Many Japanese commentators expressed regret that fewer people would get to experience wearing a kimono.” Instead of wearing kimonos as part of cultural exchange, Gulliver argues, Miller used the dress as a way to set herself apart from the culture she drew from. “Rather than black-face minstrelsy or other forms of racial masquerade, her cultural cross-dressing was a performance of whiteness. Her kimono and kneeling position, beautiful woodcut artworks, only emphasized her whiteness, in that the exoticism of the setting made her more white.” Miller herself seems to have enjoyed the “otherness” that wearing a kimono lent her. In a 1930 letter she wrote that, for a high-profile soirée, she had worn “my best Japanese costume. It made a big hit!”

Her work is similarly culturally complex. Unlike the number of other American artists who worked in a Japanese style, such as Helen Hyde, Elizabeth Keith, and Bertha Lum, Miller had grown up immersed in Japanese culture and spoke the language fluently. She saw herself, therefore, as a bridge, separate from those who experienced Japanophilia in adulthood. But there were tensions. In letters, Miller writes disparagingly of the country’s industrialization and growth, and said she saw her work as helping to keep a dying Japanese tradition alive. An uncomfortable Orientalist streak runs through the work itself, as well as in some of the more lackluster verse she published alongside her prints.

Nights in Japan—with what damp, heavy veils

Of perfume they are wrapped! From early dusk

They waft strange fragrances, sweet spice and musk,

Rich eastern scents, aromas from temple pales.

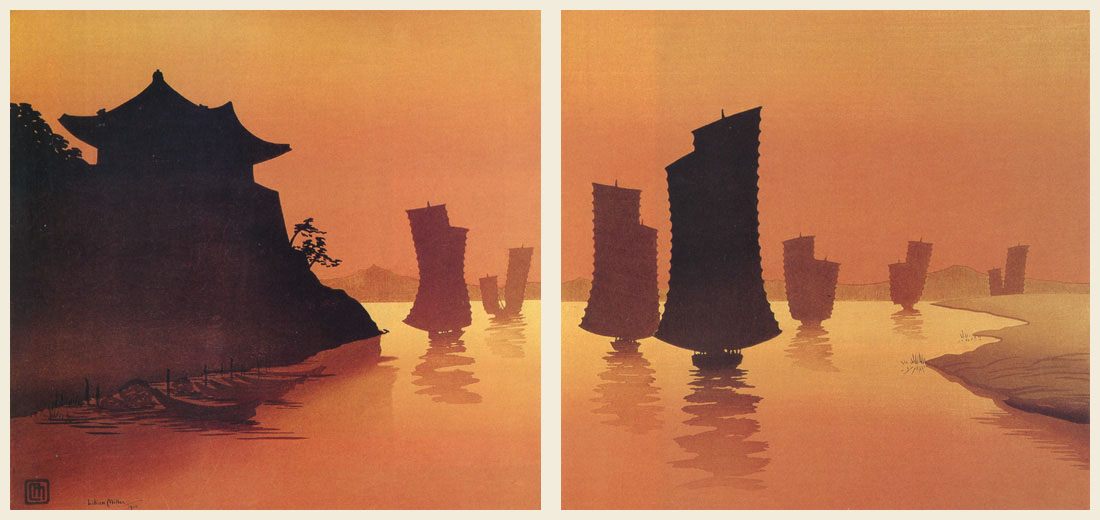

For expatriate buyers, she produced chintzy Christmas cards with seasonal greetings written down the side in a “Japanese-y” typeface. Many of these purchasers were wealthy American friends with diplomatic or business connections in Japan. Amid her father’s retirement and the onset of the Great Depression, these cards were her earliest route to making her living as an artist. Her subjects can be anachronistic and sometimes hackneyed—a very specific “image” of East Asia for a Western audience. Lazy junks bobbed in the water, women balanced bowls on their heads, and the rapid industrialization of the country was nowhere to be found. Brown attributes this not just to market forces, but to an internal struggle. “Perhaps because her own sense of identity was so fluid or indeterminate, Miller often sought to make the subject of her art—the Orient as represented by Japan and Korea—into something static,” he writes, “frozen beyond the grasp of time.”

Some of Miller’s most interesting work comes when she allowed East and West to brush up against one another. In 1929, she told a journalist from the Evening Star in Washington, D.C., that she was “American in spirit,” and that nothing had ever inspired her more deeply than the Washington Monument. “It is my ambition,” she said, “to some day make a Japanese woodblock print of the Monument, painting its grey shaft against the red background of a brilliant sunset.” Whether she did this is unknown—but she did produce striking images of American redwoods and Hawaii. When she went on a vacation to Alaska in 1941, she sketched as she went, according to an Alaska Life magazine feature by her friend Adele Buckner. “Now, as so many times before,” wrote Buckner, wife to high-ranking military officer Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., “I envied Jack’s trained eye and artistic sensitiveness. For her, once seen, this land’s elusive magic would be held until pencil and brush gave it permanence.”

But the time of America’s fascination with Japan had run out. Interest in her work had already ebbed with rising anti-Japanese sentiment, and by the time the Alaska Life piece was published, Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor. Miller was horrified, and her “American spirit” came to the fore. In a separate Vassar alumni publication, she wrote that that she was compelled, from that moment, to “put away my brushes ‘for the duration’ and find some way in which my knowledge of Japan and of Japanese could be of service to our country.” She had previously sent a large collection of prints to be exhibited in Hanover, New Hampshire. After Pearl Harbor she begged for those prints to be destroyed. “It’s been widely interpreted that she felt betrayed by Japan and therefore wanted to destroy her connection,” says Gulliver. But there was another factor—in December 1942, doctors found a large, malignant tumor in her abdomen. Barely a month later, she was dead. Though it’s purely speculative, says Gulliver, “it may have been the case that she didn’t want her work to survive her.”

Since the war, Miller’s work seems to have fallen through the cracks of art history. She is, writes Brown, “an artist who resides so resolutely between two cultures of production, national affiliation and identity,” who doesn’t fit into the category of Western artists working in Japan, or of Japanese artists trying to keep traditional printmaking methods alive. She was, she put it, caught “between two fires.” In the end, her complicated and contradictory legacy has been all but extinguished.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook