The Sauce That Survived Italy’s War on Pasta

The Futurists tried to abolish pasta and all they got was this delicious dish.

In 1932, Italian culinary magazine La Cucina Italiana awarded their Best Pasta Sauce prize to one chef’s Sugo Marinetti, or Marinetti sauce. Said sauce stood out not only for its unique combination of chopped pistachios and artichokes sauteed in butter, but also for its ironic title: the firebrand poet Filippo Marinetti, for whom the pasta sauce was named, was at that very moment fighting to banish pasta from Italy.

La Cucina Italiana, a magazine founded by wealthy, fascist editor Umberto Notari and his wife Delia Pavoni Notari, had helped launch Marinetti’s war on pasta just over a year earlier. In their December 1930 issue, Marinetti published the Manifesto of Futurist Cooking, where he declared pasta to be “an absurd Italian gastronomic religion” and called for its abolition.

The essay was one of many fascist-leaning Futurist manifestos published in the early 20th century that called for the destruction of the old in favor of the new in fields such as poetry, painting, and cinema. Along with his proponents, Marinetti, who founded the Futurist movement in 1909, blamed tradition for Italy’s declining world stature. Futurists embraced technology, war, and masculinity, while decrying museums, libraries, and many other long-held Italian treasures—pasta among them.

In the Manifesto of Futurist Cooking and the 1932 Futurist Cookbook, Marinetti imagined a world in which Italians absorbed nutrients through pills, freeing mealtime to become a form of performance art enhanced by technology, perfumes, and music. He advocated for experimental, oftentimes absurd dishes—salami cooked in coffee and cologne, for example—and the abolition of the fork and knife.

And, most significantly, Marinetti cast pasta as a prime cause of Italy’s backwardness. “Pasta is not good for Italians,” he wrote, citing a “very intelligent Neapolitan professor” who said that pasta caused disorders in the pancreas and liver, leading to “laziness, pessimism, nostalgic inactivity, and neutralism.”

Many artists and intellectuals rushed to Marinetti’s side. “Pasta is like our rhetoric,” chimed in the fascist theater critic Marco Ramperti. “Only good for filling up our mouths.” The French poet Gabriel Audisio called pasta a “dictatorship of the stomach” that necessitated an “insidious, slow process of rumination … the unctuous conciliatory rhythm of the sloth.” In Genoa, an anti-pasta advocacy group formed under the acronym PIPA, or “International Association Against Pasta,” in English.

As one might imagine, many Italians did not take well to Marinetti’s anti-pasta crusade. In the city of Aquila, women joined together to sign a letter of protest defending pasta’s honor. The mayor of Naples spoke up in favor of his city’s beloved starch, saying, “the angels in paradise eat nothing but vermicelli al pomodoro.” Marinetti, a fierce critic of Catholicism, retorted that the mayor’s claim “consecrates the unappetizing monotony of paradise and the life of the angels.” The periodical La settimana modenese called Marinetti and his Futurist allies “past their proper cooking-time.” This furor meant that Marinetti’s manifesto garnered attention in newspapers from London to Chicago, under headlines such as “Italy May Down Spaghetti.”

Marinetti’s anti-pasta campaign may have had another inspiration: Prime minister and fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who was busy attempting to convince Italians to abandon pasta in favor of rice. He wanted to wean Italy off of foreign wheat imports, which were becoming increasingly difficult to acquire amidst international sanctions and a suffering domestic economy. Rice grew well in Northern Italy, so Mussolini sent free rice samples throughout the country and bombarded Italians with pro-rice propaganda.

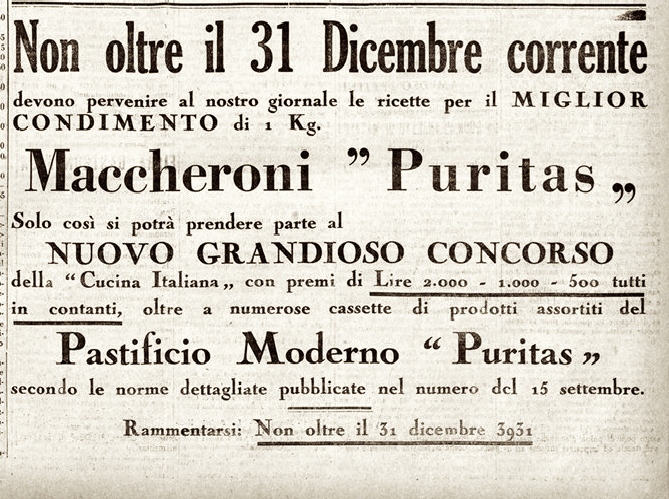

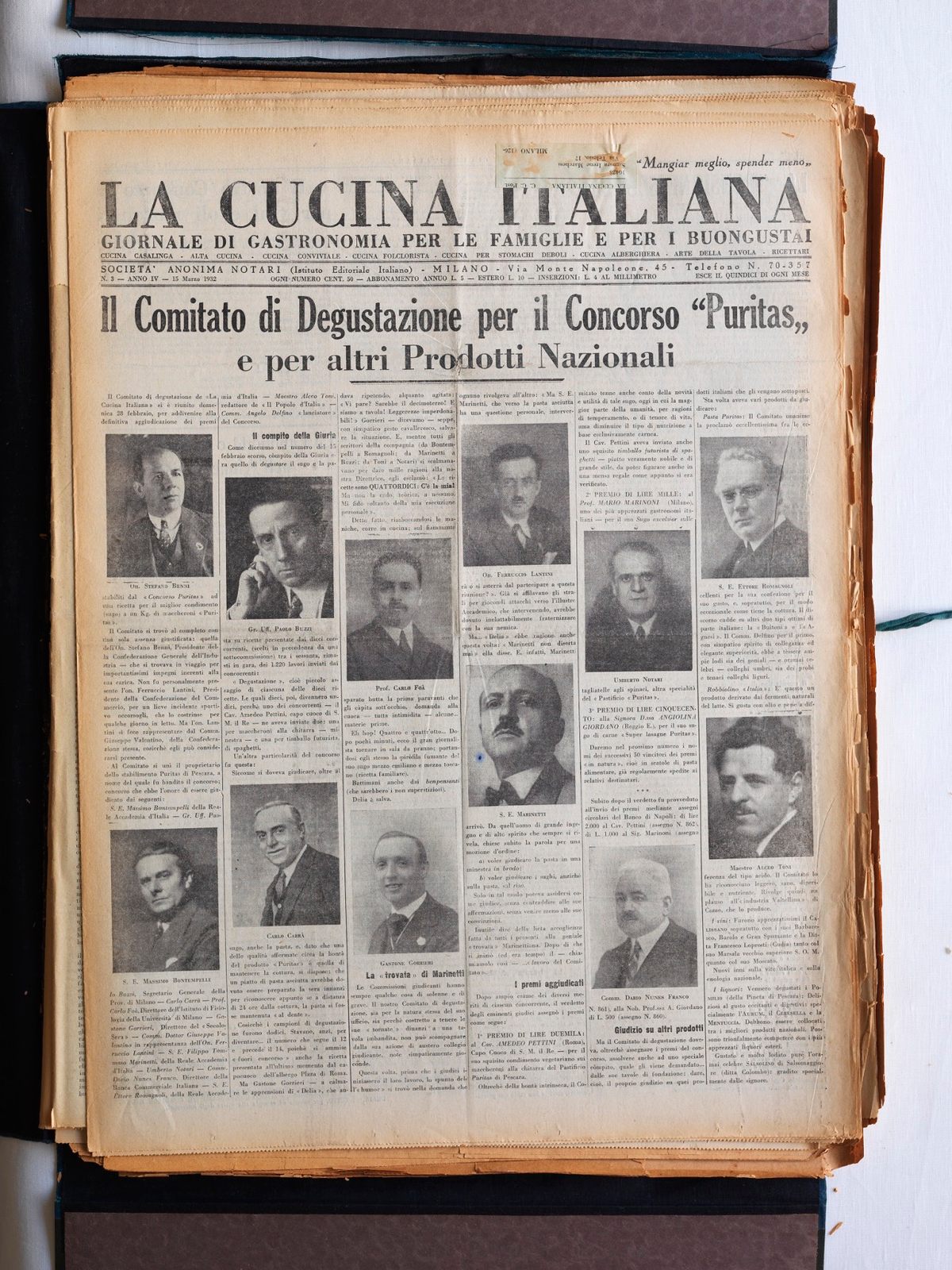

In 1931, La Cucina Italiana waded into the middle of this controversy when it hosted a contest, sponsored by the Italian pasta company Puritas, to determine who could make the best sauce to serve with one kilogram of Puritas maccheroni. La Cucina Italiana’s Notari “was a capable enough entrepreneur … to understand that the controversy would certainly have attracted readers,” writes Samanta Cornaviera, an expert in early 20th-century Italian culinary history, over email. Adding to the drama was the fact that the panel of judges, a who’s-who of Italy’s cultural elite, included the Notaris’ friend and the anti-pasta crusader himself, Marinetti. As Cornaviera recounts on her website, when it came time to judge the myriad sauces, Marinetti, in typical firebrand fashion, arrived late to the panel only to immediately demand to taste the sauces over rice or soup rather than his reviled pasta.

Though the competition attracted thousands of entrants, Marinetti and the other judges picked a predictable winner: Amedeo Pettini, former royal chef, leading food critic, and an editor of La Cucina. Pettini presented a sauce of tomato, anchovies, sauteed artichokes, ham, and chopped pistachios. He named it, somewhat surprisingly, “Marinetti sauce.”

The ironic title “was neither an insult nor a joke,” Cornaviera writes, “but a real tribute.” Pettini was a shrewd marketer, and in 1930s Italy, “it was fashionable to name recipes after national characters and heroes.” Marinetti’s name added a sarcastic cultural cachet to the sauce, although it is safe to say that Marinetti did not enjoy his namesake dish over Puritas pasta—not in public, at least.

With time, Marinetti sauce faded from public consciousness, Cornaviera writes, as did Marinetti’s fight against pasta. Both Mussolini and Marinetti died in the 1940s, and during Italy’s postwar economic boom, pasta became even more popular than ever before. Today, Cornaviera recommends that people try Sugo Marinetti, first and foremost, because it’s delicious. “That buttery and tasty sauce, the crunchiness of pistachios and the crunch of fried artichokes,” she writes, and adds, “It is also full of stories to tell.” And though it might make Marinetti roll over in his grave, Cornaviera maintains that the sauce tastes great over spaghetti.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook