How Farmers Are Preserving Israel’s Disappearing Agricultural Legacy—One Tractor At a Time

At the Tractor Museum, every machine has a story.

Nestled in a hilly corner of central Israel, among miles and miles of orange groves, an unusual museum displays one of the world’s largest tractor collections. Until the 21st century, the orchards around the museum used to be full of whirring tractors as farmers harvested the fruit trees. Back then, Israeli posters and postcards showcased the beautiful 100 square miles of orchard-dotted countryside. Known as the Sharon Plain, the groves stretched between the Mediterranean Sea and the Samarian Hills to the east. But today the farmers and their tractors are disappearing. Local officials plan to eventually flatten the groves to build new cities. In a way, the Museum Lev Hasharon for Tractor and Agricultural Machinery History is a monument to the past.

The museum, which most just call the Tractor Museum, houses 400 agricultural vehicles and tools, some of which date back to the late 19th century. The collection was started in 1991 when Israeli farmer Erez Milstein had to give up his nearby groves due to health problems. Missing his life in the fields, he bought and restored an old Porsche tractor. After that, Milstein was hooked.

He began collecting more and more tractors. He met with retired farmers or with families of farmers who had died, discovering what was hidden in the rubbish dumps of kibbutzim and moshavim, Israel’s rural, agricultural communities. As his collection grew, Milstein kept his tractors in abandoned chicken coops.

Then, his friends, and later their friends, started to join in, eager to help revive the tractors. In 2003, the group became a non-profit. They received some government funding and got to work building the museum. Today, more than 60 volunteers—former garage owners, farmers, and mechanics—help to operate the Tractor Museum. Most are octogenarians, says Milstein. “The oldest is 87 years old and he will work here until the day he dies. The youngest is in the 11th grade.”

In an interview with the Israeli digital magazine Emek, Aharon Yitzhar, a former museum volunteer who’s now 93 years old, explained that the attachment volunteers have to their tractors is intense. “Before there were tractors, there were horses, who had their personalities and caprices. When tractors replaced horses, the connection remained.” Yitzhar brought a yellow and blue Ferguson tractor to the museum, which was abandoned by a farmer “who got mad at it.”

“The tractor worked in the field for more than 40 years,” said Yitzhar. “One day it gave off a spark which ignited the field and caused a fire. The farmer was very angry with the tractor, bought a new one, and placed the dissident in detention, outside the field.”

Reviving these “dissident” and neglected tractors is a trial-and-error process that can easily take up to five years. “We contact the tractor companies in Europe and the U.S. and ask for the original parts, or the original technical specs they have in their archives,” says Shmulik Amir, one of the museum’s volunteers. “We then try to locate those parts in collections across the world.” It’s a time-consuming, but rewarding process, says Milstein. When an old tractor is finally restored, “we feel more important than doctors. We bring the dead back to life,” Milstein laughs.

“The volunteers are divided into two groups,” says Amir. “There are very technical people, whose dream is to take a piece of junk and see it drive. I belong to those who, along with the tractor, also resurrect the story.”

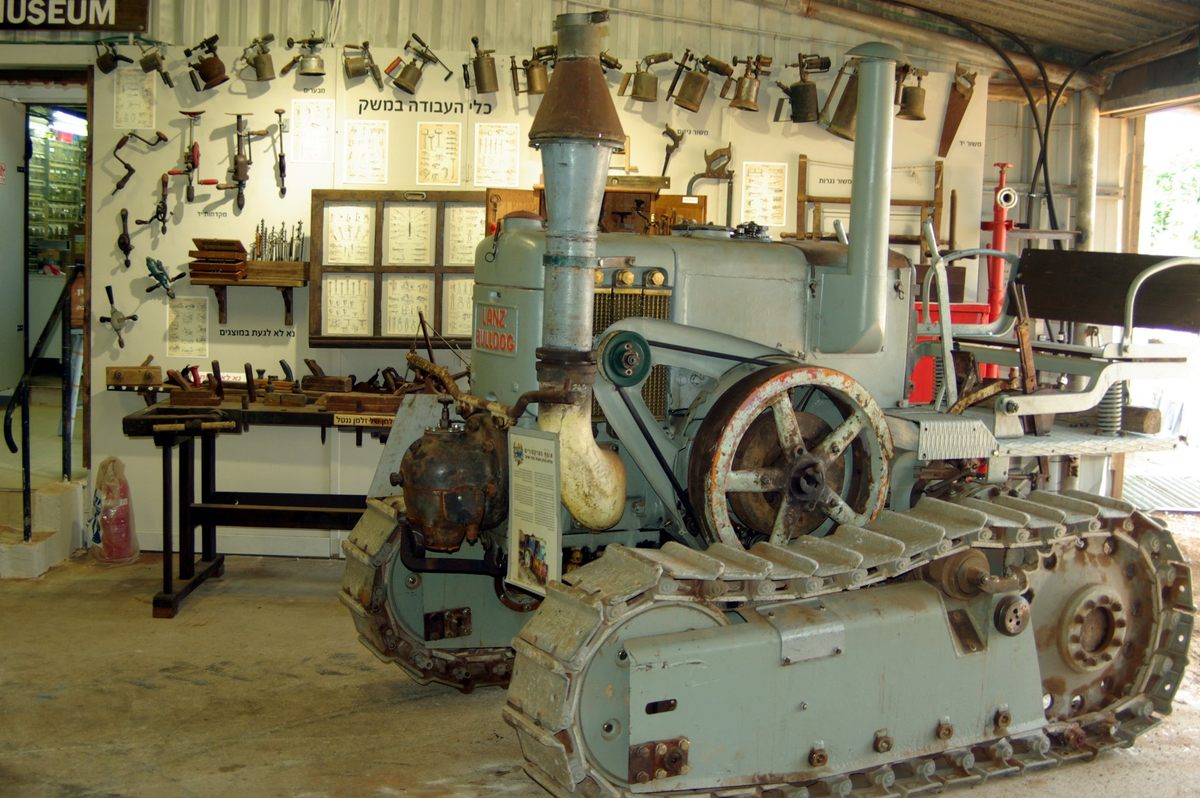

Amir leads me past rows of shiny tractors, each like an old friend to him and each with a story he is eager to share. He points out a grey tractor from the early 20th century. “This is a German Lanz tracked tractor,” he says. “This sort of vehicle towed German cannons into Poland, but in Germany there is nothing left of them. We rescued this one.” After years of work, the Lanz tractor was finally restored and collectors came knocking. “We received a 70,000 Euro bid from some German collectors, but we refused to sell. We still hear passing comments from German collectors, that this tractor belongs in Germany and not in Israel.”

Next, Amir points out a red, shabby tractor—a Romanian UTB. “This tractor was part of a package deal, in which Israel bought 800 tractors from Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu in return for him letting Romanian Jews immigrate to Israel.” Records showed “that Ceaușescu put different price tags on children, students, academics, pensioners. My first wife was a dentist who arrived in Israel from Romania with her sister and their parents. I remember I came back home and told her how her freedom was bought in tractors. She was appalled.”

Curator and museum advocate Nirit Shalev-Khalifa explains that small, local museums like the Tractor Museum are becoming more and more common. “The world is opening up. We see each other on social media. We dress the same and eat the same food. Therefore, we develop an existential need for a unique identity.” Museums that celebrate distinct, local histories are a way to remember our diverse stories.

Shalev-Khalifa likens museums to synagogues. “When you enter a place such as the Tractor Museum, you are shut in a space where only tractors matter.” Each tractor acts as a “relic,” says Shalev-Khalifa, and commemorates those who have come before. When writers die, they leave behind their words; when farmers die, they leave behind their trusty tractors and favorite work tools.

Milstein himself was born into a family of farmers who helped to establish Moshav Ein Vered in 1930, the rural farming community where the museum is now located. Among its many tractors, the museum exhibits a 1930s grass chopper, horse plow, and wooden cart that belonged to his grandparents. “As a boy, my father would drive the cart to the dairy or to buy hay.” As an adult, he cultivated vegetables and the region’s famed citrus orchards. But farmers like Milstein’s father are becoming rarer and rarer.

“Agriculture in Israel is disappearing, along with the camaraderie,” says Milstein. “This country was strong due to its united communities, and today it’s torn and polarized. This tears me up inside, but then dozens of volunteers come from the north and south to the museum, filled with enthusiasm and joy of giving and working together. They give me hope.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook