The Hidden History of the Nutmeg Island That Was Traded for Manhattan

Dutch colonists committed genocide to secure a spice monopoly. But there’s more to the story.

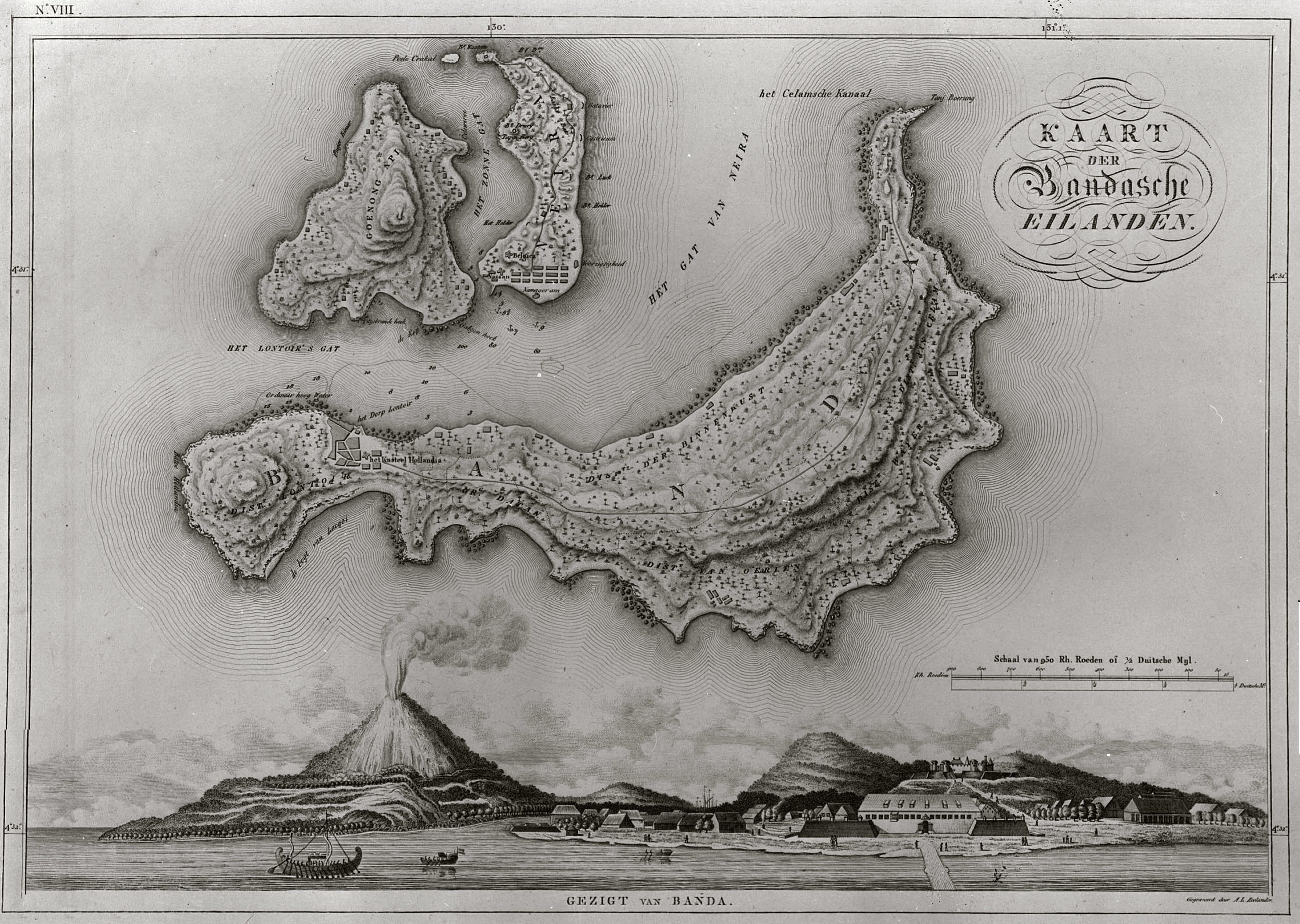

Most people know Indonesia’s Banda Islands—if they know of them at all—for one historical Snapple fact: In 1677, the Dutch traded Manhattan to the British for their claim on just one of them, a barely one-square-mile speck of land. They did so because these 11 obscure islands on the southeastern edge of modern Indonesia were, until several centuries ago, ostensibly the world’s sole source of nutmeg, which was then one of the most valuable commodities in Western Europe, largely thanks to its purported power to cure anything from gas to the bubonic plague.

For the Dutch, securing a nutmeg monopoly was worth giving up Manhattan. The tradeoff was likely a no-brainer, given the lengths they’d already gone to corner the market. In 1621, Dutch East India company officials committed genocide against the uncooperative local Bandanese people, and enslaved those who survived, just to remove one obstacle to their monopolistic dreams.

Manhattan soon developed into a cosmopolitan trade center. The Bandas, meanwhile, turned into a single-purpose, slave-driven plantation economy. As transatlantic trade and American commerce boomed, so did Manhattan. As nutmeg’s value eventually collapsed, so did the Bandas’ economy.

The simple story of the islands and their people—thrust onto the world stage because they sat on a valuable natural resource, then wholly eradicated by the unstoppable force of European colonization—is a staple of Did You Know articles on Manhattan and nutmeg. For economists, it is a potent economic parable. For food historians, a dash of flavor. Even full-fledged historians often neglect the region. When they do speak to its history, notes Timo Kaartinen, a Finnish academic whose work touches on the Bandas, they “tend to focus on the competition between different European powers.”

But this simple version of the story gets quite a bit wrong, and the full account is astounding. Rather than simply sitting on a precious resource, the Bandanese were expert traders who cornered the nutmeg market. After the Europeans’ arrival, they repelled and vexed these intruders for over a century. Even after a brutal and openly genocidal campaign laid them low, they did not vanish from history, but slipped to the peripheries of Dutch control to run new trading operations and organize a bit of nutmeg smuggling. Their regional trade dominance outlasted the colonial nutmeg craze. At least two Bandanese villages survive to this day, carrying on old traditions on the nearby Kei Islands.

Although European explorers thought of them as such, the islands were never, strictly, the world’s sole source of nutmeg. Many variants of nutmeg grow wild, or were historically cultivated, from India to Papua. Roy Ellen, a British anthropologist, tells me that early trade in nutmeg “was probably not the Bandanese nutmeg, which is the round nutmeg” we know best today, “but the long nutmeg, which was being imported from Papua and also grown in other parts” of the Moluccas, the wider “spice island” region in which the Bandas sit.

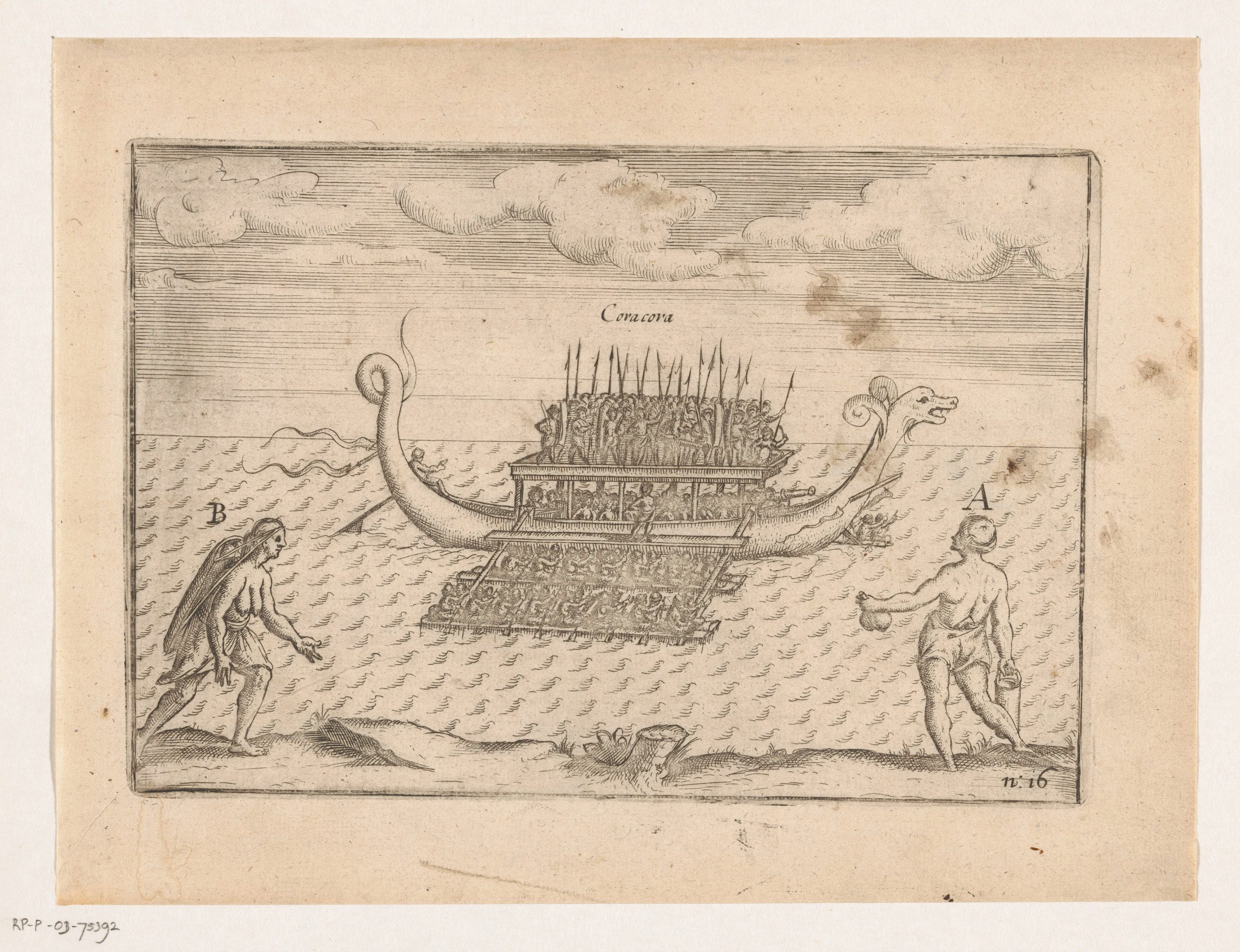

According to Ellen’s research, starting at least around the time of Christ, the Bandas acted as a vital entrepot for trade in bird of paradise plumes and other luxuries from Papua to China and ports in between. The Bandanese were master navigators, whose knowledge of the paths to, and ties with locals in, the nodes at the ends of this network made them wealthy. By the time the Europeans arrived, they lived in autonomous villages, each run by by Orang Kaya, a Malay word meaning “rich men,” which competed with each other, often in federations, for trade power.

It seems that sometime in the early centuries of the second millennium, the Bandanese began actively cultivating nutmeg. Either due to the quality of their product (Bandanese nutmeg is now the standard for flavor and potency) or clever economic maneuvering, they quickly became the key port for the nutmeg trade, frequented by Chinese, Malay, Javanese, and (by the 15th century) Arabo-Persian merchants, whose accounts inspired European dreams of the spice islands. The Bandanese sent their own trade ships as far afield as Malacca.

In the 1510s, the Portuguese became the first Europeans to arrive in the region. But these would-be colonizers struggled to muscle their way into the trade system. The Bandanese responded to their attempts at trade meddling with hostility so fierce that this first wave of Europeans essentially gave up on the Bandas within a few decades.

The Dutch showed up in the region in 1599, ready to use greater force to coerce the Bandanese to trade solely with them. And they did compel a few Orang Kaya to do so. But as soon as their war-ready boats left the harbors, locals seem to have gone back to business as usual. Much to the consternation of the Dutch, they also struck deals with the English, who first arrived in 1603, using them to balance against Amsterdam’s aggression. When a Dutch official showed up in 1609 with 1,000 soldiers and Japanese mercenaries, irate at local Orang Kaya for supposedly breaking their monopoly deals, the Bandanese tricked him into leaving most of his weapons and troops on a beach and walking inland to meet them. Then they massacred this force to send a message, fully initiating a somewhat piecemeal and on-and-off series of open conflicts with the Dutch.

This Bandanese-European conflict finally boiled over in 1621, after the Dutch forced the English to functionally abandoned their claims in the islands. Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the man in charge of Dutch East India Company operations in the region, decided to test out his theory that the nutmeg trade would be easier to control if the Dutch could clear out the Bandanese and replace them with Company-linked settlers. He found a pretext to attack Banda Besar, the largest island and a hotbed of resistance, with 1,600 Dutch troops, 80 Japanese mercenaries, and some regional slaves, the largest force (to our historical sources’ knowledge) ever seen in the region. Despite fierce resistance, they swarmed the island, cut deals with local defenders-turned-defectors, and took it within days. In response to subsequent guerilla strikes, Coen’s Japanese mercenaries beheaded and quartered 48 Orang Kaya who came to his stronghold to surrender, and displayed their body parts on bamboo sticks. His troops then scourged the islands, burning villages and enslaving almost 800 people, who were mostly sent to Batavia, a trade center on Java. Many Bandanese reportedly jumped off cliffs rather than surrender.

By the end of this Banda Besar campaign, Dutch records indicate that—out of a pre-conflict population of about 15,000 in the year 1500—only 1,000 to 2,000 Bandanese remained across all 11 islands.

“There was moral outrage over the massacre of the Bandanese already in the 17th century,” says Kaartinen, even from Dutch officials. But this outrage was relatively muted, especially given commercial interests. Coen didn’t even receive a real censure. The Dutch divided the Bandas into 68 plantations, and intrigued over the region with the English for decades.

The Bandanese weren’t washed away into the tides of history, though. A number of them had, according their own stories, migrated in the 1500s to nearby islands to run their trade networks. Survivors in the jungles of the Bandas waited until Coen left, then slipped away in hidden canoes to join these communities. Months later, a fleet of canoes, reportedly led by Orang Kaya stationed in one of these communities, showed up to evacuate more of them.

While the Dutch slowly claimed rule over the islands where the Bandanese fled, they did not take direct control of them all until the 1880s. This left the Bandanese free to help operate the trade in staple foods that even the Dutch plantations depended on, and to open profitable new trade in edible birds’ nests, sea slugs, and shark fins, to name a few items. They even helped run non-Banda (long) nutmeg cultivation, trade, and smuggling in the region, despite Dutch efforts to root these operations out. Even after the Dutch took total control in the region, Bandanese trade networks remained vital to their local economies well into the 20th century. To this day, some people who claim Bandanese descent are still reportedly accorded a high social status in the region thanks to their historical role as high-powered, economically vital traders.

“We don’t know how many actually settled in these places,” says Roy Ellen. Many pre- and post-1621 settlers likely assimilated into local cultures. A few families in some of these islands still claim Bandanese heritage, but that doesn’t give us much of a sense of their original population. On Kei Besar, though, the biggest island in the Kei chain, just under 5,000 people in two villages, Elat and Eli, some of the best ports in the region, still speak the Bandanese Turwandan language, practice Bandanese Islam, make Bandanese pottery (a unique, valued trade good until well into the 1990s), trade along Bandanese networks, sing Bandanese songs, and sail regularly to the Bandas to affirm their heritage and perform rites.

“When the Bandanese speak of colonial events” today, says Kaartinen, “they refuse to be cast as victims or refugees.”

Even in the Bandas, the Bandanese story did not end in 1621. The Dutch brought in slaves to work their plantations. But they were forced to lean on Bandanese slaves, as experts and educators in nutmeg cultivation. While the Bandanese slave population dwindled, they left traces of their culture in the slave population and later indentured servants and migrant workers. Research by the Australian anthropologist Phillip Winn shows that most of the more than 18,000 people in the Bandas today acknowledge that they come from many different lands, but still believe that they are legitimately Bandanese. They perform rituals that they believe have roots in ancient Bandanese practices to affirm that identity, and speak of pre-colonial Bandanese history as their own.

In 1982, locals in the Bandas also took over the state-owned nutmeg growing enterprise, which still made up a major part of the local economy. They split the groves equally among local families, building collectives that buy from harvesters, then sell nutmeg on to external interests. This, speculates American anthropologist Amy Jordan, seems like a return to pre-colonial cultivation. If so, it is a compelling coda to an incredible history of ingenuity and resistance.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook